A cross-sectional survey of experiences and outcomes of using testosterone replacement therapy in UK men

Highlight box

Key findings

• 86% delayed treatment for at least a year, including 24% who experienced symptoms for over 5 years before seeking care.

• Men over 50 years old are 1.61 times more likely to delay treatment compared to younger men.

• The majority (85%) reported testosterone replacement therapy as effective or very effective, coupled to improvements in overall quality of life (work performance, social interactions, and personal satisfaction), mental wellbeing, self-esteem, confidence and appearance.

What is known and what is new?

• Testosterone deficiency (TD) remains largely underdiagnosed and undertreated due to nonspecific symptoms that may be misinterpreted as normal aspects of the ageing process or depression.

• This is the first study to quantify average time from the onset of symptoms to a formal diagnosis of TD among men in the United Kingdom.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• There is a need for increased awareness, timely diagnosis and equitable access to effective treatment for TD.

Introduction

In the last decade, there has been a significant shift in the awareness of healthcare professionals (HCPs) and the general public regarding the importance of hormonal health in later life, particularly around hormone replacement therapy (HRT), to address the symptoms of menopause (1-3). Despite this increased interest around female hormones, there has been little comparable advancement in the progress of hormonal health for men, including male hypogonadism, also referred to as testosterone deficiency (TD).

There are many reasons for a lack of progression in male hormonal health, including lack of public and HCP awareness about TD, misleading outcomes from historical studies, cultural and societal misconceptions that testosterone is just a “sex and muscles” hormone, and that optimal levels may not be required later in life (4-6).

Testosterone is the primary sex hormone in men. It is essential for the development and maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics, significantly impacting metabolism, cognition, personality and mood, sexual function and libido levels (7). As testosterone affects nearly every system in the body, suboptimal levels may negatively impact male health and wellbeing.

TD prevalence varies widely depending on diagnostic criteria and treatment thresholds used. There is ongoing debate as to the threshold testosterone in men with TD that requires testosterone replacement therapy (TRT); the National Health Services (NHS) treat patients with total testosterone levels <8.6 nmol/L (8) whereas national guidelines define hypogonadism as total testosterone <12 nmol/L and free testosterone <0.225 nmol/L (9); the European Male Ageing Study (8,10) reported that among 3,369 men aged 40–79 years old, 17% had biochemically low testosterone levels (defined as total testosterone <11 nmol/L and free testosterone <220 pmol/L), with 2–12% of men over 40 potentially suffering from clinical symptoms of TD. More recently, Hayek et al. (9) assessed the prevalence of low testosterone levels in men with type 2 diabetes, reporting that 37% of the cohort had TD (defined as a total testosterone level <3 ng/mL), while 29% of the same cohort had symptoms consistent with low testosterone [assessed using the Androgen Deficiency for Aging Male (ADAM) questionnaire] (9). Pertinently, while up to 75% of men maintain normal testosterone levels into older age, 25% do not (11), suggesting that TD is not a function of normal ageing and may have a significant impact on the quality and health outcomes for men.

There is ample evidence that TRT and its various modalities are safe and well tolerated by most men (12); the choice of the best product is dependent on preference, pharmacogenetics, treatment burden, cost and insurance coverage (13). Moreover, the symptomatic and metabolic benefits of TRT outweigh the risks associated with this treatment (14,15). A systematic review performed by Araujo et al. has suggested that untreated, low testosterone in men is associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular-related death (16). As more evidence emerges around the prevalence and negative health impact of low testosterone in men, and as TRT becomes more popular, various institutions including the British Society of Sexual Medicine (11), the Society for Endocrinology (12), and the British Journal of General Practice (17) have published guidance on the symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of TD. This guidance will be critical to support clinicians in treating symptoms of TD. However, alongside this, it is also increasingly necessary to have a clear understanding of the needs and experiences of men in this area.

This research investigated personal perceptions and experiences of men who pursued TRT treatment for low testosterone symptoms. Specifically, we sought to explore associations between demographics, duration of symptoms, side effects and the effectiveness of treatment in past and current users of TRT. We present this article in accordance with the CHERRIES reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2024-738/rc) (18).

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of adult men with TD and experience using TRT in the UK to explore the knowledge, attitudes and perceptions regarding symptoms and treatment options for low testosterone. This adopted a quantitative methodology, using adaptive questioning with data collected via an online tool comprising a total of 52 questions. The online survey could be accessed using a personal computer or smartphone.

Consent and data protection

Participants were required to read the participant information sheet (PIS) prior to proceeding with the survey; the PIS included information regarding the study’s aims, the protection of participants’ personal data, their right to withdraw from the study at any time, which data were stored, where and for how long, who the investigator was, the purpose of the study and survey length. Participants were informed that this was a voluntary survey without any monetary incentives, but were offered the possibility of accessing findings at a later stage. Data collected was stored on a secure, encrypted database at Imperial College London, and only the research team could access the eSurvey results. All responses were pseudo-anonymised to ensure confidentiality by assigning each respondent a unique study ID. Only the participants’ demographic data, including age in years, sex, ethnicity, residence, education level and employment status, were recorded.

Participant recruitment

The link to the electronic survey was published and made available on the Imperial College Qualtrics platform between 25 April 2024 and 10 September 2024 (5 months). The open survey could be accessed by anyone with a link and took 10 minutes to complete. Survey participants were primarily recruited through email lists of the largest private clinics in the UK (approximately 5,800 users at the time of survey collection). Additionally, the survey link was disseminated through social media and word of mouth to professional medical organisations and the researchers’ professional network of doctors.

The majority of participants in this research were current or previous TRT users recruited from Manual, Optimale and H3Health, allowing us to leverage the largest private clinics in the UK offering digital health and in-person testosterone therapy. Based in the UK; these services support approximately 5,800 men (assigned male sex at birth) with testosterone deficiency, offering nationwide access to specialist care. All treatments were prescribed by registered HCPs in accordance with clinical guidelines, requiring eligible blood tests [total testosterone (TT) levels of <12 nmol/L and free testosterone (FT) levels of <0.225 nmol/L and accompanied by clinical symptoms suggestive of hypogonadism]. Participants were recruited via email using mailing lists derived from individuals who had previously agreed to receive communications related to research opportunities. All active patients at the time of the survey received an email invitation to participate in the study, followed by three reminders.

Electronic survey setup

The survey consisted of a structured questionnaire designed to assess knowledge, attitudes and behaviours around low testosterone and available treatments, adopting a quantitative methodology drawing upon comparable research design in women’s health (19). The survey comprised a total of 52 items distributed over 20 pages (1–4 questions per page). The survey is available for review in https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/tau-2024-738-1.pdf.

The survey was hosted on the Imperial Qualtrics XM (a cloud-based platform for creating, collecting and analysing surveys) (20), designed to capture opinions from a diverse cross-section of UK adult men. All survey items were conditional and required a response; respondents were prompted to complete outstanding items before leaving the survey page on which the item was contained. Items were not randomised or alternated, and most items included a ‘None of above/prefer not to say’ option. Respondents were able to review their answers before submitting them (through a back button). Usability and technical functioning of the online survey were tested before publishing.

Respondents were not excluded from the survey if they completed the items too quickly. The minimum completed survey was timed at approximately 3.4 minutes. Incomplete surveys were timed out after 7 days. Only completed responses were included in the dataset for analysis. Out of 1,384 responses received, we excluded 330 incomplete responses, 89 respondents who had never used TRT, and 54 duplicate entries identified by IP addresses. This resulted in a final sample of 905 unique respondents.

Statistical analysis

Medians and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated for continuous respondent characteristics, and N (%) was calculated for categorical characteristics, overall and by length of TRT usage (in years). We examined attitudes and behaviours by age group and TRT experience and perceptions using Chi-squared test and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Associations between demographics (including age) and delayed access to care (defined as 2+ years of experiencing TD symptoms without seeking treatment) were assessed using univariable and multivariable logistic regressions. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All analyses were performed using STATA, version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics approval

The Imperial College Research Ethics Committee (ICREC) granted ethical clearance for this study (No. ICREC #6990009). All experimental protocols were approved by ICREC. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. All subjects provided electronic consent by selecting the relevant tick box at the start of the online survey. Consent for publication is not applicable.

Patient and public involvement

No patient was involved. The study protocol and online survey were developed in collaboration with Menwell Ltd., which included feedback from 15 lay members representing diverse employment roles and cultural backgrounds. The Survey was reviewed during beta testing to improve usability and wording of questions.

Results

Demographic profile of respondents

The response rate from the private clinics involved was 24%. A final sample of 905 out of 1,386 total responses was included in the analysis (completion rate: 65.2%).

Participant characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The median age of respondents was 44.0 years (IQR, 38.0–52.0 years), with a median BMI of 28.4 kg/m2 (IQR, 26.2–31.4 kg/m2), classifying most as overweight, and a median self-reported overall health score of 8.0/10.0 (IQR, 7.0–8.0), as assessed via EQ-5D. The majority identified as White (93%), sexually active (91%), employed (90%), partnered or married (77%), and 51% had completed a university degree or higher. Individuals who reported delayed symptom presentation were more likely to be slightly older with a higher BMI. All respondents reported their assigned sex at birth as male, with 99% maintaining the same gender identity, while the remaining 1% identified as “other”, including non-binary, agender, or “prefer not to say”. In view of this, we opted to refer to respondents as “men” throughout this article, however we acknowledge that low testosterone and symptoms relating to low testosterone are not limited to cisgender men.

Table 1

| Demographic | Symptom length | P value** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–6 months (N=25) | 7–12 months (N=104) | 13–24 months (N=252) | 2–5 years (N=300) | 5+ years (N=224) | Total (N=905) | ||

| Age, years | 44 (38.0, 48.0) | 41 (35.0, 49.0) | 44 (38.0, 51.0) | 45 (40.0, 53.0) | 45.5 (39.0, 53.0) | 44 (38.0, 52.0) | 0.002 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.8 (25.7, 32.9) | 28.1 (25.6, 30.7) | 28.7 (26.3, 31.4) | 28.3 (26.2, 31.2) | 28.9 (26.8, 32.3) | 28.4 (26.2, 31.4) | 0.19 |

| EQ5D (overall health score) | 8 (7.0, 9.0) | 8 (7.0, 9.0) | 8 (7.0, 8.0) | 8 (7.0, 8.0) | 8 (6.0, 8.0) | 8 (7.0, 8.0) | 0.06 |

| qADAM score | 34 (31.0, 36.0) | 35 (30.0, 37.0) | 34 (30.0, 37.0) | 34 (30.0, 38.0) | 33 (28.0, 36.0) | 34 (30.0, 37.0) | 0.08 |

| Male sex assigned at birth | 25 [100] | 104 [100] | 252 [100] | 300 [100] | 224 [100] | 905 [100] | |

| White ethnicity | 24 [96] | 94 [90] | 237 [94] | 272 [91] | 215 [96] | 842 [93] | 0.34 |

| Education status | 0.72 | ||||||

| A levels or equivalent | 4 [16] | 14 [13] | 37 [15] | 36 [12] | 29 [13] | 120 [13] | |

| GCSEs or equivalent | 1 [4] | 10 [10] | 24 [10] | 37 [12] | 27 [12] | 99 [11] | |

| Other | 0 | 3 [3] | 9 [4] | 6 [2] | 11 [5] | 29 [3] | |

| Postgraduate degree (e.g., MA, MS) | 4 [16] | 21 [20] | 52 [21] | 63 [21] | 32 [14] | 172 [19] | |

| Primary school | 0 | 0 | 2 [1] | 2 [1] | 0 | 4 [0] | |

| Secondary school / high school | 3 [12] | 3 [3] | 8 [3] | 20 [7] | 11 [5] | 45 [5] | |

| Undergraduate degree (e.g., BA, B) | 9 [36] | 36 [35] | 77 [31] | 96 [32] | 75 [33] | 293 [32] | |

| Vocational qualification (e.g., N) | 4 [16] | 17 [16] | 43 [17] | 40 [13] | 39 [17] | 143 [16] | |

| Employment status | 0.49 | ||||||

| Employed fulltime | 21 [84] | 97 [93] | 226 [90] | 262 [87] | 190 [85] | 796 [88] | |

| Employed parttime | 1 [4] | 3 [3] | 4 [2] | 8 [3] | 5 [2] | 21 [2] | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 | 1 [1] | 3 [1] | 10 [3] | 3 [1] | 17 [2] | |

| Retired | 3 [12] | 2 [2] | 15 [6] | 14 [5] | 21 [9] | 55 [6] | |

| Student | 0 | 1 [1] | 1 [0] | 3 [1] | 3 [1] | 8 [1] | |

| Unemployed | 0 | 0 | 3 [1] | 3 [1] | 2 [1] | 8 [1] | |

| Current healthcare professional | 0.06 | ||||||

| No | 20 [80] | 93 [89] | 238 [94] | 280 [93] | 208 [93] | 839 [93] | |

| Yes | 5 [20] | 11 [11] | 14 [6] | 20 [7] | 16 [7] | 66 [7] | |

| Marital status | 0.19 | ||||||

| Divorced | 1 [4] | 3 [3] | 16 [6] | 22 [7] | 21 [9] | 63 [7] | |

| Married | 14 [56] | 52 [50] | 132 [52] | 169 [56] | 124 [55] | 491 [54] | |

| Partnered in a domestic relationship | 4 [16] | 26 [25] | 67 [27] | 67 [22] | 44 [20] | 208 [23] | |

| Single | 5 [20] | 21 [20] | 37 [15] | 41 [14] | 33 [15] | 137 [15] | |

| Widowed | 1 [4] | 2 [2] | 0 | 1 [0] | 2 [1] | 6 [1] | |

| Smoking status | 0.32 | ||||||

| No | 16 [64] | 55 [53] | 114 [45] | 154 [51] | 104 [46] | 443 [49] | |

| Current smoker | 0 | 2 [2] | 15 [6] | 10 [3] | 12 [5] | 39 [4] | |

| Past smoker | 9 [36] | 47 [45] | 123 [49] | 136 [45] | 108 [48] | 423 [47] | |

| Sexually active | 0.41 | ||||||

| No | 1 [4] | 6 [6] | 22 [9] | 27 [9] | 26 [12] | 82 [9] | |

| Yes | 24 [96] | 98 [94] | 230 [91] | 273 [91] | 198 [88] | 823 [91] | |

| Mental condition | 0.48 | ||||||

| No | 24 [96] | 97 [93] | 235 [93] | 276 [92] | 200 [89] | 832 [92] | |

| Yes | 1 [4] | 7 [7] | 17 [7] | 24 [8] | 24 [11] | 73 [8] | |

| Depression | <0.001 | ||||||

| No | 16 [64] | 57 [55] | 130 [52] | 147 [49] | 69 [31] | 419 [46] | |

| Yes | 9 [36] | 47 [45] | 122 [48] | 153 [51] | 155 [69] | 486 [54] | |

| Anxiety | 0.01 | ||||||

| No | 11 [44] | 48 [46] | 113 [45] | 129 [43] | 69 [31] | 370 [41] | |

| Yes | 14 [56] | 56 [54] | 139 [55] | 171 [57] | 155 [69] | 535 [59] | |

| Eating disorder | 0.29 | ||||||

| No | 24 [96] | 100 [96] | 246 [98] | 297 [99] | 216 [96] | 883 [98] | |

| Yes | 1 [4] | 4 [4] | 6 [2] | 3 [1] | 8 [4] | 22 [2] | |

| Diabetes | 0.051 | ||||||

| No | 25 [100] | 104 [100] | 245 [97] | 295 [98] | 213 [95] | 882 [97] | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 7 [3] | 5 [2] | 11 [5] | 23 [3] | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.26 | ||||||

| No | 25 [100] | 104 [100] | 250 [99] | 294 [98] | 218 [97] | 891 [98] | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 2 [1] | 6 [2] | 6 [3] | 14 [2] | |

| Stroke | 0.30 | ||||||

| No | 25 [100] | 103 [99] | 248 [98] | 300 [100] | 221 [99] | 897 [99] | |

| Yes | 0 | 1 [1] | 4 [2] | 0 | 3 [1] | 8 [1] | |

| Hypertension | 0.54 | ||||||

| No | 21 [84] | 88 [85] | 201 [80] | 241 [80] | 172 [77] | 723 [80] | |

| Yes | 4 [16] | 16 [15] | 51 [20] | 59 [20] | 52 [23] | 182 [20] | |

| Cholesterolemia | 0.003 | ||||||

| No | 19 [76] | 92 [88] | 209 [83] | 230 [77] | 160 [71] | 710 [78] | |

| Yes | 6 [24] | 12 [12] | 43 [17] | 70 [23] | 64 [29] | 195 [22] | |

| Access to NHS | 0.48 | ||||||

| No | 18 [72] | 56 [54] | 152 [60] | 166 [55] | 136 [61] | 528 [58] | |

| Yes | 3 [12] | 23 [22] | 53 [21] | 60 [20] | 48 [21] | 187 [21] | |

| Unsure | 4 [16] | 25 [24] | 47 [19] | 74 [25] | 40 [18] | 190 [21] | |

| Access to private healthcare | 0.78 | ||||||

| No | 4 [16] | 16 [15] | 33 [13] | 52 [17] | 34 [15] | 139 [15] | |

| Yes | 21 [84] | 84 [81] | 203 [81] | 229 [76] | 179 [80] | 716 [79] | |

| Unsure | 0 | 4 [4] | 16 [6] | 19 [6] | 11 [5] | 50 [6] | |

| Received routine testing of symptoms | 0.007 | ||||||

| No | 12 [48] | 40 [38] | 90 [36] | 118 [39] | 64 [29] | 324 [36] | |

| Yes | 13 [52] | 64 [62] | 162 [64] | 182 [61] | 160 [71] | 581 [64] | |

| Received formal low testosterone diagnosis | 0.04 | ||||||

| No | 2 [8] | 1 [1] | 11 [4] | 5 [2] | 3 [1] | 22 [2] | |

| Yes | 23 [92] | 103 [99] | 241 [96] | 295 [98] | 221 [99] | 883 [98] | |

| TRT status | 0.30 | ||||||

| Currently using TRT | 25 [100] | 101 [97] | 236 [94] | 289 [96] | 216 [96] | 867 [96] | |

| Past user | 0 | 3 [3] | 16 [6] | 11 [4] | 8 [4] | 38 [4] | |

| TRT type | 0.68 | ||||||

| Intramuscular testosterone (injection) | 13 [52] | 34 [33] | 92 [37] | 114 [38] | 83 [37] | 336 [37] | |

| Intramuscular testosterone (injection)* | 8 [32] | 17 [16] | 68 [27] | 67 [22] | 55 [25] | 215 [24] | |

| Intranasal testosterone gel | |||||||

| Intranasal testosterone gel* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 [1] | 0 | 2 [0] | |

| Subcutaneous testosterone (injection) | 14 [56] | 72 [69] | 162 [64] | 204 [68] | 147 [66] | 599 [66] | |

| Subcutaneous testosterone (injection)* | 10 [40] | 59 [57] | 136 [54] | 158 [53] | 120 [54] | 483 [53] | |

| Topical testosterone gel/cream | 4 [16] | 19 [18] | 24 [10] | 31 [10] | 27 [12] | 105 [12] | |

| Topical testosterone gel/cream* | 2 [8] | 7 [7] | 16 [6] | 16 [5] | 13 [6] | 54 [6] | |

| Combination of methods used | 5 [20] | 21 [20] | 29 [12] | 55 [18] | 33 [15] | 143 [16] | |

| Length of TRT use | |||||||

| 0–6 months | 10 [40] | 39 [38] | 99 [39] | 118 [39] | 81 [36] | 347 [38] | |

| 7–12 months | 8 [32] | 29 [28] | 69 [27] | 85 [28] | 57 [25] | 248 [27] | |

| 1–2 years | 3 [12] | 22 [21] | 54 [21] | 64 [21] | 50 [22] | 193 [21] | |

| 3–4 years | 2 [8] | 9 [9] | 19 [8] | 28 [9] | 25 [11] | 83 [9] | |

| 5+ years | 2 [8] | 5 [5] | 11 [4] | 5 [2] | 11 [5] | 34 [4] | |

| Effectiveness of TRT | |||||||

| 1 (not effective at all) | 0 | 6 [6] | 13 [5] | 16 [5] | 10 [4] | 45 [5] | |

| 2 | 1 [4] | 5 [5] | 10 [4] | 14 [5] | 10 [4] | 40 [4] | |

| 3 | 0 | 5 [5] | 15 [6] | 15 [5] | 15 [7] | 50 [6] | |

| 4 | 9 [36] | 35 [34] | 91 [36] | 95 [32] | 75 [33] | 305 [34] | |

| 5 (very effective) | 15 [60] | 53 [51] | 123 [49] | 160 [53] | 114 [51] | 465 [51] | |

Data are presented as median (IQR) or n [%]. *, exclusive use of TRT method; **, P value refers to chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, or Kruskal Wallis test for continuous variables. BMI, body mass index; EQ-5D, EuroQol five-dimension questionnaire; IQR, interquartile range; qADAM, quantitative Androgen Deficiency for Aging Male questionnaire; TRT, testosterone replacement therapy.

The vast majority (96%) of respondents were active TRT users (compared to past users), with 38% starting within the past 6 months, 27% within 7–12 months, and 21% between 1–2 years. Subcutaneous and intramuscular injections were the most common methods of administration (66% and 37%, respectively), followed by creams and gels (12%). Specifically, 53%, 24% and 6% used these methods exclusively in that same order, while 15% utilised a combination of testosterone therapies.

Health-seeking behaviours

Among the 905 men who sought TRT, 86% delayed presentation for at least one year, with 24% experiencing symptoms for more than 5 years before seeking treatment. Age was a significant predictor: in crude models, those who were older than 50 years were 1.79 times more likely to experience prolonged symptoms compared to those who were younger [51+ vs. ≤40 years: odds ratio (OR) 1.78; P=0.001]. Multivariable associations adjusting for ethnicity, marital status, employment status, and education confirmed these findings, with men older 51 years and older 1.61 times more likely to have delayed presentation than those aged 40 years or younger (OR 1.61; P=0.01; Table 2).

Table 2

| Age group (years) | Sample N | Univariable | Multivariable** | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |||

| ≤40 | 292 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |||||

| 41–50 | 349 | 1.30 | 0.95, 1.89 | 0.10 | 1.25 | 0.91, 1.731 | 0.17 | |

| 51+ | 264 | 1.78 | 2.36, 2.50 | 0.001 | 1.61 | 1.13, 2,39 | 0.01 | |

*, delayed access defined as experiencing symptoms for more than 2 years prior to seeking care; **, adjusted for ethnicity, marital status, employment status, and education. CI, confidence interval; N, number of participants; OR, odds ratio; ref, reference category.

The majority (81%) of respondents turned to online sources to learn about TD, while fewer (18%) felt comfortable discussing hormonal health with their peers (available online: https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/tau-2024-738-2.pdf). Less than a quarter (24%) felt adequately equipped with the knowledge and resources to manage their symptoms and navigate treatment options within the UK healthcare system. When seeking professional advice, 44% consulted their general practitioner (GP), 29% saw a specialist (e.g., urologist) and 28% consulted another HCP. Nearly a third (31%) engaged with online forums, and 20% relied on websites to explore hormonal health and treatment options.

Before considering TRT, the most common lifestyle modifications included changes to exercise routines (66%), dietary adjustments (62%), the use of testosterone boosters, including non-TRT supplements (46%) and stress management techniques (32%). The primary motivations for seeking treatment for low testosterone were the desire to improve personal relationships, including intimacy and communication (80%), and/or to enhance physical appearance (55%). Most respondents were not influenced by concerns about social acceptance of TRT or societal perceptions of masculinity when considering treatment for TD (59% and 58%, respectively).

Experience with TRT

Patient expectations during medical consultations primarily focused on obtaining a diagnosis (77%), understanding their available treatment options (64%), discussing potential side effects (51%) and understanding the long-term implications of TRT (50%). Most patients (71%) anticipated a gradual improvement in symptoms with TRT, although 24% expected a more rapid response. Preferences for consultation format varied, with 19% favouring in-person consultations, 18% opting for telephone or online consultations, and the remainder expressing no strong preference.

A significant proportion (85%) of patients reported TRT as highly effective, with longer-term users (defined as having used TRT for more than 1 year) being 2.6 times more likely to rate TRT as effective or very effective compared to recent starters (1+ vs. 0–6 months: OR 2.6, P<0.001; data not shown).

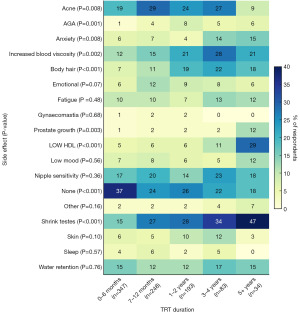

Figure 1 details the occurrence of side effects, overall and stratified by TRT duration. Overall, 29% of respondents reported no side effects. The most reported side effects included acne (23%), testicular atrophy or reduced sperm production (24%), nipple sensitivity or gynecomastia (18%), increased blood viscosity (16%) and fluid retention (15%). When analysing TRT treatment duration, we found a significant increase in incidence of self-reported testicular atrophy (P<0.001) and increased blood viscosity (P=0.002). However, the incidence of other side effects remained low and showed only minor variation between short- and long-term users, suggesting a consistent safety profile of TRT over time (Figure 1).

Overall, TRT users reported the positive impact of TRT in their overall quality of life (including work performance, social interactions and personal satisfaction; 75%), mental wellbeing (71%), self-esteem and confidence (69%) and appearance (61%).

Discussion

Summary of key findings

We analysed data collected from 905 British adult men aged 21–80 years with TRT experience. This study expands on previous suggestions that there are significant challenges in the management and treatment-seeking behaviours of men with TD. Despite the considerable impact of TD on quality of life, 86% of the respondents surveyed delayed seeking care for more than a year, with 24% of patients experiencing symptoms for over five years before consulting a healthcare provider. Older men, who are at higher risk for TD, were also significantly more likely to delay seeking treatment.

TRT was reported as effective or very effective by 85% of respondents, noting overall increased quality of life (75%), mental wellbeing (71%), self-esteem and confidence (69%), appearance (63%), with few experiencing side effects from treatment. However, the lack of routine testing and awareness in the English primary care setting remains a major barrier to streamlining timely access to effective treatment regimen, particularly patients with TD symptoms.

Comparison with existing literature

Few studies characterised the average time from the onset of symptoms to a formal diagnosis of TD in men due to symptoms TD being relatively non-specific and consequently misinterpreted as part of the ageing process or as a result of apathy or depression (21,22). Studies that evaluated this diagnostic delay more often focused on symptoms of erectile dysfunction as the primary presenting complaint (23,24), despite TD manifesting in a broader range of symptoms such as loss of libido, oligospermia, weakness, increased anxiety, fatigue and anaemia.

Conversely, several studies have assessed HCPs’ awareness and understanding of TD diagnosis and treatment, highlighting the gap between clinical knowledge and patient engagement. Anderson et al. surveyed 443 participants, including 88 HCPs, and found that while over 90% of new TD cases were considered treatable, half of HCPs reported that patients rarely initiated conversations about their condition (25). Similarly, a study in British Columbia investigated the awareness of TD among Primary Care physicians, reporting that while 96% were aware of TD and its health implications, more than half (57%) of the surveyed physicians encountered difficulties in diagnosing or treating TD due to a lack of education and awareness around hypogonadism care (26). These findings suggest general awareness of TD may not translate into clinical confidence in managing the condition, resulting in delays to providing timely and effective care.

Several studies reported that education around the benefits and possible risks of TRT remained a key determining factor for whether a patient-initiated treatment. Gilbert et al. (27) surveyed 97 urological patients and found that half were unsure of the risks of such treatments. Other studies that assessed patient satisfaction and motivation while on TRT indicate that patients were generally satisfied with their treatment, with mood and concentration being reported as some of the biggest improving factors (28). These observations are supported by a wealth of evidence, more recently summarised in the British Society of Sexual Medicine Guidelines on Male Adult Testosterone Deficiency, with Statements for Practice (11) also highlighting the metabolic, physical, mental, sexual and long-term health benefits of TRT. Interestingly, despite the evidence of the effectiveness of TRT and the positive impact it has on health and wellbeing outcomes, there was a high dropout rate from TRT (27,29). Whilst the reasons for this dropout rate are unclear, they may potentially be associated with the cost (out-of-pocket expense) of accessing TRT outside of NHS, changing priorities, and/or because the patient was able to resolve their symptoms of TD to the extent that they felt TRT was no longer required. There is a need for continuous patient education, emphasising both the potential benefits of TRT and the importance of adhering to longer-term treatment plans to maintain the achieved results.

Implications for policy, practice and research

Delays in seeking care for TD may be indicative of broader systemic issues, including insufficient awareness amongst both the public and healthcare providers. The reliance on online information, with 84% of men turning to the internet for guidance coupled to the discomfort some men face in discussing hormonal health with their peers (18%), highlighting both how individuals access information today, the lingering stigma around TD, and potential gaps in patient awareness about available clinical support for testosterone therapy. Furthermore, many healthcare providers are unfamiliar with the nuances of TD, often leading to delayed diagnoses and treatment. Combined, this knowledge gap may further discourage patients from initiating care during their interactions with their HCPs, as patients may hesitate to discuss testosterone concerns due to uncertainty about their symptoms or wariness of being dismissed, potentially perceiving their concerns as non-urgent. Additionally, the development of updated clinical guidelines may promote education around health and well-being outcomes for men by addressing common misconceptions and gaps in general awareness about the benefits and risks of TRT among both patients and healthcare providers.

While low testosterone can manifest through various interconnected physical, mental and sexual symptoms, our research indicates that men frequently seek medical attention when these changes start to affect intimate relationships or self-perception. Specifically, sexual dysfunction, such as decreased libido, erectile difficulties (30), and noticeable alterations in body composition (31) appear most likely to initiate consultation. Such socially and personally prominent signs tend to be perceived as urgent, whereas more subtle mental health changes may be disregarded or attributed to “normal ageing”, contributing to delayed help-seeking. Identifying which clinical triggers motivate men to seek care can inform more targeted interventions and education aimed at earlier recognition and treatment of TD.

There is also a critical need for greater attention to ensure more equitable access to TRT across diverse populations. More research is needed to understand the underlying socioeconomic and racial barriers (such as healthcare costs, lack of awareness or cultural stigma) to accessing TRT care, as these factors may prevent underrepresented groups from seeking and receiving timely care. Further research into TD that evaluates the health economic impact and lost productivity to economies would highlight the pressing unmet need in men’s health provision. Population health data could also support the case for streamlining timely and equitable access to care, coupled with policy directions that call for further investments in men’s health. This research could be used to guide the development of policy directives to promote further investments in men’s health (an area that continues to be overlooked) and to address disparities in equitable access to care and support from underserved segments of society.

Study strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first quantitative study to quantify average time from the onset of symptoms to a formal diagnosis of TD among men in the UK and includes a large sample size of 905 participants with a diverse demographic profile. We acknowledge several limitations, including the electronic distribution of the survey, which may have inadvertently excluded individuals with limited digital access or literacy. The principal limitations of this study are concerned with (I) reliance on self-reported data, which may introduce bias as participants’ responses may be influenced by social desirability or lack of understanding around hormonal health, and (II) the cross-sectional nature of the study, which precludes the determination of causality between variables. Additionally, while the full questionnaire was not formally validated, this does not limit the information gathered from the survey; we also incorporated the quantitative Androgen Deficiency for Aging Male questionnaire (qADAM) and EQ-5D instruments to assess symptoms of TD and overall health. Both measures have been widely used in clinical and research settings. Furthermore, in this cross-sectional study, participants were asked about any current TD symptoms that they may be experiencing, rather than symptoms that they may have experienced in the past. As such, we are unable to perform analyses to comment on which symptoms/signs are most likely to drive men to seek medical attention. Another limitation of our study is that we mainly accessed participants through clinic email lists, professional organisations and researcher networks, making it less likely to capture responses from individuals using testosterone outside formal clinical oversight. Men who self-prescribe or obtain testosterone from unregulated sources such as black-market products and online distributors may exhibit different demographic patterns, motivations, dosing regimens, and side effect profiles.

The observed associations between long-term (>5 years) testosterone therapy and potential prostate growth and reduced HDL cholesterol warrant cautious interpretation. While these effects could partly reflect therapy-specific mechanisms, normal ageing, preexisting metabolic factors, and lifestyle confounders must also be considered. Future longitudinal research is required to distinguish changes attributable to TRT from those driven by the aging process alone. Additionally, while we collected data on various forms of testosterone administration, we did not capture information on adjunctive therapies, such as human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) or other gonadotropins that some clinicians may use to preserve fertility.

We also acknowledge that the demographic profile of study participants largely consisted of white and university-educated men who were already engaged with the healthcare system for TRT rather than the general population of men with low testosterone symptoms. While this demographic may align with the broader population accessing TRT in the UK, it may also limit the generalisability of our findings. In addition, while information on gender identity was collected, for the purposes of confidentiality and study scope, we did not collect or report on factors for low testosterone in these individuals. A further limitation is the small proportion of respondents over age 61 years, despite TD increasing with age. This likely reflects our online recruitment strategy, which may lower engagement among older individuals, and a tendency for older men to view symptoms as ‘normal’ aging and not seek further assessment.

Conclusions

Despite the positive health effects of TRT, the vast majority (85%) of men with TD surveyed delayed seeking care for their symptoms for more than a year, likely due to a combination of factors, including cultural and societal narratives that trivialise TD and incorrectly associate symptoms with ‘normal ageing’. As the prevalence of TD continues to increase, more research coupled with coherence education and awareness campaigns are needed to help educate men and HCPs alike regarding the signs and symptoms of TD, and possible treatment options.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank staff at Menwell Ltd. for their support in survey beta testing and development.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CHERRIES reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2024-738/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2024-738/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2024-738/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2024-738/coif). A.E.O. and B.H. are supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) Northwest London. V.N.L. is a paid employee (Clinical research Lead) at Manual (Part of Menwell Ltd.). D.H. is employee of Menwell Ltd. J.F. is the Director of Men’s Health at Manual [the founder of H3Health; now part of Menwell Ltd. (t/a Manual)]. H.J. is a paid employee (Researcher in Innovation) at Manual (Part of Menwell Ltd.). The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The Imperial College Research Ethics Committee (ICREC) granted ethical clearance for this study (No. ICREC #6990009). All experimental protocols were approved by ICREC. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. All subjects provided electronic consent by selecting the relevant tick box at the start of the online survey. Consent for publication is not applicable.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Pop AL, Nasui BA, Bors RG, et al. The Current Strategy in Hormonal and Non-Hormonal Therapies in Menopause-A Comprehensive Review. Life (Basel) 2023;13:649. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lobo RA. Hormone-replacement therapy: current thinking. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2017;13:220-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal S, Alzahrani FA, Ahmed A. Hormone Replacement Therapy: Would it be Possible to Replicate a Functional Ovary? Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:3160. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carruthers M. Time for international action on treating testosterone deficiency syndrome. Aging Male 2009;12:21-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaplan AL, Hu JC, Morgentaler A, et al. Testosterone Therapy in Men With Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol 2016;69:894-903. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hackett G, Kirby M, Edwards D, et al. British Society for Sexual Medicine Guidelines on Adult Testosterone Deficiency, With Statements for UK Practice. J Sex Med 2017;14:1504-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nassar GN, Leslie SW. Physiology, Testosterone. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- Tajar A, Forti G, O'Neill TW, et al. Characteristics of secondary, primary, and compensated hypogonadism in aging men: evidence from the European Male Ageing Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:1810-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al Hayek AA, Khader YS, Jafal S, et al. Prevalence of low testosterone levels in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. J Family Community Med 2013;20:179-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu FC, Tajar A, Beynon JM, et al. Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. N Engl J Med 2010;363:123-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hackett G, Kirby M, Rees RW, et al. The British Society for Sexual Medicine Guidelines on Male Adult Testosterone Deficiency, with Statements for Practice. World J Mens Health 2023;41:508-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jayasena CN, Anderson RA, Llahana S, et al. Society for Endocrinology guidelines for testosterone replacement therapy in male hypogonadism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2022;96:200-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shoskes JJ, Wilson MK, Spinner ML. Pharmacology of testosterone replacement therapy preparations. Transl Androl Urol 2016;5:834-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosen RC, Wu F, Behre HM, et al. Quality of Life and Sexual Function Benefits of Long-Term Testosterone Treatment: Longitudinal Results From the Registry of Hypogonadism in Men (RHYME). J Sex Med 2017;14:1104-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Diem SJ, Greer NL, MacDonald R, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Testosterone Treatment in Men: An Evidence Report for a Clinical Practice Guideline by the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2020;172:105-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Araujo AB, Dixon JM, Suarez EA, et al. Clinical review: Endogenous testosterone and mortality in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:3007-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Sharefi A, Wilkes S, Jayasena CN, et al. How to manage low testosterone level in men: a guide for primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2020;70:364-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang DR, Goodship A, Webber I, et al. Experience and severity of menopause symptoms and effects on health-seeking behaviours: a cross-sectional online survey of community dwelling adults in the United Kingdom. BMC Womens Health 2023;23:373. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qualtrics. Qualtrics 2025. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/citing-qualtrics/

- Tostain JL, Blanc F. Testosterone deficiency: a common, unrecognized syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Urol 2008;5:388-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rivas AM, Mulkey Z, Lado-Abeal J, et al. Diagnosing and managing low serum testosterone. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2014;27:321-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shabsigh R, Perelman MA, Laumann EO, et al. Drivers and barriers to seeking treatment for erectile dysfunction: a comparison of six countries. BJU Int 2004;94:1055-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajfer J. Relationship between testosterone and erectile dysfunction. Rev Urol 2000;2:122-8.

- Anderson JK, Faulkner S, Cranor C, et al. Andropause: knowledge and perceptions among the general public and health care professionals. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M793-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pommerville PJ, Zakus P. Andropause: knowledge and awareness among primary care physicians in Victoria, BC, Canada. Aging Male 2006;9:215-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilbert K, Cimmino CB, Beebe LC, et al. Gaps in Patient Knowledge About Risks and Benefits of Testosterone Replacement Therapy. Urology 2017;103:27-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kovac JR, Rajanahally S, Smith RP, et al. Patient satisfaction with testosterone replacement therapies: the reasons behind the choices. J Sex Med 2014;11:553-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McLaren D, Siemens DR, Izard J, et al. Clinical practice experience with testosterone treatment in men with testosterone deficiency syndrome. BJU Int 2008;102:1142-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsujimura A. The Relationship between Testosterone Deficiency and Men's Health. World J Mens Health 2013;31:126-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isidori AM, Giannetta E, Greco EA, et al. Effects of testosterone on body composition, bone metabolism and serum lipid profile in middle-aged men: a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;63:280-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]