Psychological aspects of Peyronie’s disease

Introduction

François Gigot de La Peyronie, surgeon to King Louis XV of France, was the first to describe Peyronie’s disease (PD) in 1743 (1). PD is an acquired fibrotic disorder (disorganized collagen deposition) in the tunica albuginea. This scar tissue or “plaque” builds up in the tunica albuginea and results in penile deformities. These deformities can be simple, multiple, or complex, which most commonly results in penile curvature. The deformities can also consist of penile indentations, tapering of the penis, or in the shape of an hourglass. PD may be associated with erectile dysfunction (ED) and/or pain on erection or flaccid state.

There is no consensus concerning the etiology and the prevalence PD. Depending on the source, the prevalence rates range from 3.2% to 8.9% (2,3). PD is most likely under diagnosed, especially in men with ED who are not capable of achieving an erection hard enough that would show the true severity of the deformity. In a review of a prospective database, Tal et al. reported a PD prevalence of 15.9% following radical prostatectomy (4). The average patient age at diagnosis has been reported to be around 52–57 years of age (3,5,6).

The pathophysiology of PD still remains poorly understood and is considered to be multifactorial. Genital traumatism is considered to be the primary etiologic factor, but the physiopathologic theories for PD are multiple: genetic predisposition, autoimmune disorder, collagen alterations, and overexpression of pro inflammatory cytokines. According to Mulhall, trauma might be the primary initiating factor. This trauma may lead to plaque development in a man who is genetically predisposed and whose tunica albuginea has a status of local impaired wound healing (7). For most men, PD does not resolve on its own. In 2006, Mulhall et al. reported the natural history of PD in 246 men. Only 12% of men had spontaneous recovery, while 40% remained stable and 48% of men saw their condition worsen over time (5).

PD can have a significant negative impact on a man’s mood and quality of life. Although the psychological impact of PD has generally been understudied, there has been a growing body of literature that has assessed the impact PD can have on men’s mental health and relationships. The aim of this study is to review the current literature on the psychological and relationship impact of PD.

Methods

We performed a MEDLINE search limited to English language literature using the terms: “Peyronie’s Disease AND Psychological OR Psychosocial”, and select references were included for review.

Review of the literature

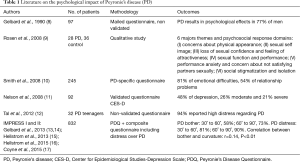

In general, there is a paucity of research on the psychological effects of PD. Nevertheless, of the studies that have been conducted, depression and relationship distress are prevalent and consistent across studies (see Table 1 for summary of the literature).

Full table

In the first study to characterize the distress related to PD, Gelbard et al. [1990] surveyed 97 men with PD (8). These authors used a non-validated questionnaire, sent by mail. The topics of this questionnaire included: pain, intercourse functionality, bending of the penis, overall effect of PD, psychological effect of PD, treatments for PD, and disease progression. The assessment of distress was one question, which asked about the “psychological effects” of PD, and one question that asked if these psychological effects changed over time. A total of 77% of men reported psychological effects due to PD. These psychological symptoms improved in 28%, worsened in 36%, and did not change in 36% of men. Among men who reported an improvement in their disease, 48% declared that they thought about their problem frequently or all the time (8).

Smith et al. [2008] surveyed men with PD treated in a single clinical practice. The aim of this cross-sectional study was to determine the prevalence of emotional and relationship difficulties attributed to PD, and to identify risk factors associated with these difficulties. The authors used a self-developed, non-validated questionnaire that contained one question about PD-related “emotional problems” and one question about PD-related “relationship problems” (10). They reported that 81% of the 245 men had emotional difficulties and 54% attributed relationship problems to PD (10). Among men with relationship problems, 93% had emotional problems. Among men with emotional problems, 62% had relationship problems. The presence of relationship problems and loss of penile length were shown by multivariable analysis to be significantly associated with emotional problems (respectively eight- and three-fold increase). Men able to have intercourse reported less relationship problems. Loss of penile length, low libido, and penile pain were also risk factors for relationship problems (10).

In 2008, Nelson and colleagues studied the chronology of depression and distress in men with PD (11). To our knowledge, this is the only study that used validated instruments to assess distress and depression. The authors used the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), a widely used and validated self-report questionnaire for the assessment of depressive symptoms (18). Ninety-two patients with PD were assessed, and 48% were classified as depressed on the CES-D (26% moderate and 21% severe) (11). The degree of depression significantly correlated with being single (r=0.22, P˂0.05) and subjectively reported penile shortening (r=0.27, P˂0.05). Patients answered these questionnaires on an average of 18 months after initial assessment of PD. The CES-D score remained consistently high over time, and there was no significant difference between groups according to the length of time since diagnosis of PD.

Recently, following a long development process, the Peyronie’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ) has been created to assess the physical and psychological impact of PD. The PDQ is a specific, self-administered questionnaire designed to quantitatively measure psychosexual consequence of PD. The PDQ is comprised of three subscales: (I) Peyronie’s psychological and physical symptoms (six items); (II) Peyronie’s symptom bother (six items); and (III) penile pain (three items) (13). The Investigation for Maximal Peyronie’s Reduction Efficacy and Safety Studies (IMPRESS) I and II used the PDQ as a secondary outcome. The IMPRESS studies were two, large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical studies (n=832) that examined the effects of collagenase clostridium histolyticum (CCH) treatment in men with PD.

A few publications have reported on the PDQ distress data from these IMPRESS studies. Coyne et al. reported that at baseline, 53% of men in IMPRESS I experienced moderate distress related to their PD and 31% experienced severe distress (19). In IMPRESS II, at baseline, 45% and 33% experienced moderate and severe distress respectively related to PD (19). Gelbard et al. reported that 72% of patients with severe penile deformity (>60˚) and 58% with mild/moderate deformity (˂60˚) were “very bothered” or “extremely bothered” upon last observation of their erect penis (14). Distress was weakly correlated with increasing deformity (14), while the psychological symptoms were also weakly correlated with greater penile curvature. Similarly, Hellstrom et al. reported that PDQ symptom bother, psychological and physical symptoms, was weakly correlated with clinical improvement in penile curvature (16). There was no difference in the correlations among improvement in PDQ domain scores and improvement in penile curvature between subgroup with penile curvature 30˚–60˚ and the subgroup penile curvature 60˚–90˚ (16). Importantly, Gelbard et al. [2015] found no significant difference between median PD bother when they stratified by the duration of PD, suggesting that patients do not psychologically “adjust” to the disease.

It is important to understand the context of the PDQ and the IMPRESS trials to appropriately interpret these data. First, the use of the PDQ is limited to patients engaging in routine vaginal intercourse. This may impact the data from the PDQ as men who are able to have intercourse reported significantly less relationship problems (10). Also of concern is that single men may not have completed the PDQ, and the data suggest that depression in men with PD is significantly correlated with being single (11). In terms of the IMPRESS studies, the inclusion and exclusion criteria may influence the results reported. For example, the studies excluded patients who were in the acute phase, had ventral curvature, or had non-PD sexual dysfunction. Taking into account the limitations of the PDQ and the eligibility criteria of the IMPRESS trials, it could be argued that the rate of psychological bother reported in these studies underestimates the true level of psychological distress.

In terms of subgroups of men with PD, Tal et al. investigated the characteristics of PD in teenagers, which is an at-risk population for psychological distress. These authors assessed 30 teenagers who had PD. Nearly all the teenagers in the study (94%) suffered from high distress. Moreover, 34% sought medical consulting for anxiety/mood disorder, and 28% had a negative encounter with a sexual partner related to PD (12). Farrell et al. [2013] reported on 23 homosexual men with PD and compared them to 200 heterosexual men with PD. These authors reported high distress in homosexual men with PD and a negative impact on intimate relationships; however, these figures were not statistically different from heterosexual men (20).

In 2008, Rosen et al. conducted a qualitative study in men with PD and men without PD. This type of qualitative work helps explain the quantitative data, reviewed above, from a patient perspective. Rosen and colleagues collected data from 13 focus groups and reported the psychosocial and sexual aspects of PD. In total, 64 men were included, composed of 28 with PD and 36 without PD (9). The primary goal of this study was to identify major themes of concern among men with PD. They reported six themes and psychosocial response domains:

- Concerns about physical appearance;

- Sexual self image;

- Loss of sexual confidence and feeling of attractiveness;

- Sexual function and performance;

- Performance anxiety and concern about not satisfying partners sexually;

- Social stigmatization and isolation.

Regarding body image and self esteem, men described themselves as “”abnormal”, “ugly”, “disgusting”, “like a cripple”, a “half man”. They reported diminution of their masculinity, and some of them described feeling of shame (9). Many men reported that they lost their sexual confidence, or ability to initiate sex with a partner, while most reported a decrease in sexual interest. The loss of sexual confidence caused feelings of high distress. Many men expressed performance anxiety, reinforced by a fear of not being able to satisfy their partners sexually. Most were embarrassed and uncomfortable with any discussion about sexuality and PD. None of men in the focus groups had sought medical help with their partner (9). Additionally, many men expressed a sense of stigmatization and isolation. This sense led to difficulties in speaking about their disease with sexual partners or healthcare professionals, and, as a result, men felt that they were not receiving the emotional support and understanding they needed (9).

Discussion

The research in this area confirms the clinical impressions of men with PD, which is that depression and relationship distress is prevalent. Approximately 50% of men with PD suffer from depressive symptoms and upwards of 80% report distress related to this condition (11,19). It appears that these rates remain relatively stable over time as the Nelson et al. [2008] and Gelbard et al. [2013] both conducted analyses that indicated a stable trajectory of psychological burden (11,14). High rates of relationship stress were also reported, as over 50% of men reported that PD had negatively impacted their relationship (10). The qualitative work helps us understand the nature of this distress, as men reported feeling a loss of sexual self-confidence, a sense of isolation, and expressed that they viewed themselves as a “cripple” or a “half man”.

PD is often underestimated by physicians who consider PD a functional problem with no vital affect. If we consider depressive symptoms, PD becomes a societal and economic problem. Nelson et al reported that PD in the United States might represent 250 million workdays missed, $66 billion of estimated replacement costs for depression-related absenteeism, and 2.5 billion in estimated incremental medical costs because of this depression (11). These projections highlight the importance of sexual dysfunction like PD, particularly in an average age of the PD population of 52–57 years (3,5,6).

The data presented in the studies above highlight that general practitioners, urologists, and sexual medicine professionals must be aware of psychosocial aspects of PD. Importantly, these studies outlined possible predictors of this distress in men with PD, and practitioners should be aware that single men, patients with loss of penile length, and those with the inability to have intercourse may be at higher risk to report distress. Taken in total, these studies indicate that those who actively treat PD should assess for distress or depressive symptoms in these men. The standard assessment of PD could include the PDQ, and at least two questions on individual and relationship distress, or the use of a validated questionnaire such as the CES-D. If any of these assessments indicate distress, these men should be quickly referred to a mental health professional. To do this, we suggest the PD practitioner develop a referral relationship with a mental health professional in their area. This should include providing educational information about PD to this mental health professional, so this referral source would have more than a basic understanding of PD.

Although the literature exploring distress and depression in men with PD is a “good start” to help us understand how men emotionally react to the disease, there are a number of recommendations for continued work in this area. First, the use of validated instruments to assess distress is essential to improve this literature. Nelson et al. was the only study that used a validated questionnaire for depression, and a number of the previously discussed studies assessed distress or relationship quality with one question, which was developed by the authors (11). The development of the PDQ is clearly an advancement in this area and should be used in future research; however, other validated instruments for constructs such as depression, sexual self-esteem, sexual bother, and sexual quality of life exist, and should be used in future studies. Second, longitudinal studies to better characterize the chronology of distress, depression, and relationship quality in men with PD are needed. Nelson et al. and Gelbard et al. both examined distress related to time since initial presentation, and the original Gelbard et al. [1990] asked about “changes” in psychological effects. However, these were all cross-sectional studies, which did not fully capture the natural evolution of the distress related to PD.

Another important weakness in this literature is that researchers have not explored the experience of partners of men with PD, or truly focused on the relationship aspects related to PD. Smith et al. reported that 54% of men had relationship problems due to PD, and that loss of penile length, low libido, and penile pain were also risk factors for relationship problems (10). However, this study assessed relationship problems with only one question. There are a number of validated instruments that assess relationship quality that could be used in future research. Furthermore, there have been no studies that have assessed the distress in partners of men with PD. Finally, only minimal data (n=27) on distress exists concerning gay patients with PD. In our experience, at a high volume PD center, we noted that negative effects might impact gay men more than straight men. Farrell et al. [2013] found no difference between gay and straight men related to distress and the impact on relationships, however, this type of work needs to be replicated with more studies and larger sample sizes (20).

Conclusions

Among men with PD, there is high prevalence of depression and relationship distress, which remains relatively stable over time. The significance of untreated psychological illness in men with PD can be a large burden in society. Taken in total, these studies indicate that those who actively treat PD should assess for distress or depressive symptoms in these men. The standard assessment of PD could include the PDQ and at least two questions on individual and relationship distress, or the use of a validated questionnaire.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Androutsos G. François Gigot de La Peyronie(1678-1747), benefactor of surgery and supporter of the fusion of medicine and surgery, and the disease that bears his name. Prog Urol 2002;12:527-33. [PubMed]

- Mulhall JP, Creech SD, Boorjian SA, et al. Subjective and objective analysis of the prevalence of Peyronie's disease in a population of men presenting for prostate cancer screening. J Urol 2004;171:2350-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer U, Sommer F, Klotz T, et al. The prevalence of Peyronie's disease: results of a large survey. BJU Int 2001;88:727-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tal R, Heck M, Teloken P, et al. Peyronie's disease following radical prostatectomy: incidence and predictors. J Sex Med 2010;7:1254-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mulhall JP, Schiff J, Guhring P. An analysis of the natural history of Peyronie's disease. J Urol 2006;175:2115-8; discussion 2118. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindsay MB, Schain DM, Grambsch P, et al. The incidence of Peyronie's disease in Rochester, Minnesota, 1950 through 1984. J Urol 1991;146:1007-9. [PubMed]

- Mulhall JP. Expanding the paradigm for plaque development in Peyronie's disease. Int J Impot Res 2003;15 Suppl 5:S93-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gelbard MK, Dorey F, James K. The natural history of Peyronie's disease. J Urol 1990;144:1376-9. [PubMed]

- Rosen R, Catania J, Lue T, et al. Impact of Peyronie's disease on sexual and psychosocial functioning: qualitative findings in patients and controls. J Sex Med 2008;5:1977-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith JF, Walsh TJ, Conti SL, et al. Risk factors for emotional and relationship problems in Peyronie's disease. J Sex Med 2008;5:2179-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nelson CJ, Diblasio C, Kendirci M, et al. The chronology of depression and distress in men with Peyronie's disease. J Sex Med 2008;5:1985-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tal R, Hall MS, Alex B, et al. Peyronie's disease in teenagers. J Sex Med 2012;9:302-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gelbard M, Goldstein I, Hellstrom WJ, et al. Clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability of collagenase clostridium histolyticum for the treatment of peyronie disease in 2 large double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled phase 3 studies. J Urol 2013;190:199-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gelbard M, Hellstrom WJ, McMahon CG, et al. Baseline characteristics from an ongoing phase 3 study of collagenase clostridium histolyticum in patients with Peyronie's disease. J Sex Med 2013;10:2822-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hellstrom WJ, Feldman R, Rosen RC, et al. Bother and distress associated with Peyronie's disease: validation of the Peyronie's disease questionnaire. J Urol 2013;190:627-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hellstrom WJ, Feldman RA, Coyne KS, et al. Self-report and Clinical Response to Peyronie's Disease Treatment: Peyronie's Disease Questionnaire Results From 2 Large Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Studies. Urology 2015;86:291-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coyne KS, Currie BM, Thompson CL, et al. The test-retest reliability of the Peyronie's disease questionnaire. J Sex Med 2015;12:543-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, et al. Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study. Am J Epidemiol 1977;106:203-14. [PubMed]

- Coyne KS, Currie BM, Thompson CL, et al. Responsiveness of the Peyronie's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ). J Sex Med 2015;12:1072-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farrell MR, Corder CJ, Levine LA. Peyronie's disease among men who have sex with men: characteristics, treatment, and psychosocial factors. J Sex Med 2013;10:2077-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]