The impact of ejaculatory dysfunction upon the sufferer and his partner

Introduction

The work with sexual dysfunction in men is often difficult due to the fact that their relationship with their sexuality is marked by a blocked perception of the inner world of thoughts and emotions. This tendency to externalize negative feelings, such as fear or shame, explains why an organic etiology and a pharmacological treatment approach are more attractive than a psychological approach and psychotherapy or sex therapy for many patients (1).

Many men believe that their sexual response can be automatic, which is a defense against their own vulnerabilities and needs. The individual basic conditions for a satisfying sexuality are blurred and their history reveals only rudimentary sexual competence at best (1).

Apart from the pressure to perform and the fear of failure, the loss of an erotic world is the most significant problem in relation to male sexuality (1).

As occurs with other domains of the male sexual response, the ejaculatory function cannot be evaluated outside the dyadic process and without taking into account the men’s and women’s cognition of the condition and how their subjective perception impacts on the evaluation of the relationship and sexual quality (2).

The factors and processes outlined above constitute the broader framework that translates into behavioral problems often encountered in clinical practice. Sex easily becomes mechanical and the couple loses the rhythm of giving and receiving pleasure-oriented touching (3).

Although the distress of the sufferer and his partner has been a motivating factor in leading men with ejaculatory dysfunction to seek medical help, few objective or prospective evaluations of the effects on the couple have been reported (4).

It is noteworthy that specialized literature has been dealing with ejaculatory disorders in a heterogeneous manner. Comparatively, there are far more studies on premature ejaculation (PE) than on delayed ejaculation (DE) and even fewer studies on other male orgasm disorders. Therefore, this article focuses on the two most studied ejaculatory disorders. It is important to emphasize that the matter presented in this article can also be considered for other ejaculatory disorders, since all of them relate to a failure of control, changing the intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT), with consequences for both men and their partners.

Definition and classification issues

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) classifies ejaculatory disorders as DE (302.74) and PE (early ejaculation) (302.75) (5). Such conditions are given different names in the literature, such as rapid ejaculation, in the case of PE, and inhibited or retarded ejaculation in the case of DE.

The prevalence of PE remains unclear. This is mostly due to the difficulty to determine what constitutes clinically relevant PE. Vague definitions without specific operational criteria, different modes of sampling, and non-standardized data acquisition have led to a great variability in estimated prevalence (6-9). Most studies on the prevalence of PE utilized the DSM, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (IV-TR) definition (10), and characterized PE as the “most common male sexual dysfunction,” with a prevalence rate of 20–30% (11-13). As the DSM-IV-TR definition lacks objective diagnostic criteria, the high prevalence of PE reported in many of these surveys is a source of ongoing debate. It is appropriate to bear in mind that there are significant differences between PE prevalence rates in the general population and clinic settings because the majority of men with PE do not seek treatment (14).

Recently, the IELT has become popular as a diagnosis criterion for PE (14). The International Society of Sexual Medicine’s and DSM-5’s definition of PE are based on 1 minute, in terms of an IELT, for the purpose of clinical studies. There is evidence that the prevalence of lifelong PE is unlikely to exceed 4% of the general population. Additionally, a prevalence of approximately 5% of acquired PE and lifelong PE in general populations is consistent with epidemiological data indicating that approximately 5% of the population have an ejaculation latency equal to less than 2 minutes (14).

Lifelong or chronic DE remains one of the least prevalent and least understood of all the sexual disorders and confronts both researchers and clinicians with many unresolved problems. Much remains to be found about why men differ so dramatically in ejaculatory latency or why men capable of ejaculating with masturbation are unable to ejaculate intravaginally. Both the neurobiological vulnerability and the biographical, psychodynamic, or interpersonal factors responsible for this dysfunction need to be elucidated (1).

The psychodynamic of ejaculatory dysfunction

The identification of the reciprocal influences of partners on each other’s sexual function and dysfunction has been overshadowed by a focus on individual factors (15). Nonetheless, studies have begun to clarify the dynamics and reciprocal relationship of one partner’s sexual experience, function, physical and mental health and well-being with the other partner’s sexual functioning and satisfaction (16).

There are multiple psychological explanations as to why a man develops PE or DE. Unfortunately, none of the theories evolve from evidence-based studies (17). Although untested, the theories are thought-provoking (18).

Psychoanalyst Karl Abraham was the first to consider the psychodynamic basis of PE in 1927. He theorized that the cause of PE was an infantile narcissism, resulting in an excessive importance being placed on the penis, and a symptom of unconscious conflicts involving hostility toward, or fear of, women (19). Bernard Schapiro found little or no support for this hypothesis and speculated that a man with PE had specific biological organ vulnerabilities that directed the expression of the individual’s psychological conflicts (20).

Kaplan considered that PE could be the result of an unconscious, deep-seated hatred of woman (21). By ejaculating quickly, the man symbolically “soils” the woman and robs her of sexual pleasure. This theory assumes that vaginal intercourse is the primary source of sexual pleasure for women (18). In addition, it does not explain PE in homosexual men. Moreover, the link between male hostility towards women and PE lacks empirical evidence. Later, Kaplan suggested that most men with PE do not have personality disorders (22).

Hartmann et al. characterized men with PE as preoccupied with thoughts about controlling their orgasms, with anxious anticipation of a possible failure, thoughts about embarrassment and thoughts about keeping their erections (23).

DE is understudied and therefore poorly understood. Nevertheless, this dysfunction can result in a lack of sexual fulfillment for both the man and his partner (24). A somatic condition may explain the disorder, and indeed, any procedure, disease, or medication that disrupts sympathetic or somatic innervations to the genital region has the potential to affect ejaculatory function and orgasm (25-27). However, some men with DE have no somatic factors that could explain the disorder. As a result of their inability to ejaculate, these men also do not experience orgasm (28). Some studies suggest that a number of cognitive and behavioral factors may ultimately be combined in men with DE to result in attenuated subjective arousal and therefore significant difficulty in reaching orgasm during coitus (28-30).

DE is also affected by the interplay between an individual’s genetics, the neurophysiology that regulates ejaculation latency, biology, behaviors, and psychosocial/cultural factors (31-33). The list of causes of DE is extensive, and a full discussion of each one is beyond the scope of this review (34).

Fear and shame derived from personal or religious beliefs may cause psychological conflict and inhibit ejaculation: fear of fathering a child or fear of harm inflicted on either the partner or self from coitus (35). Idiosyncratic masturbation and sexual fantasy used only during masturbation have also been associated with DE during partnered sex (31,36,37).

In many cases, the man has conditioned himself to ejaculate only in response to a particular, often very vigorous, touch by his own hand on a particular spot of his penis. The result can be a completely conditioned sexual dysfunction (1).

The common final pathway of these factors is the irrational fear of ejaculating intravaginally. The wide array of possible conflicts and fantasies that has been described can only be briefly listed and assigned to some broader categories: incest fears, castration fears, fears of hurting the woman, fear of loss of control, hostility and anger toward woman, fear of sperm loss, paraphilic impulses (1).

However, some theories on the etiology of DE maintain that these factors are of particular importance in patients with this dysfunction. As sexual excitement is dependent on specific stimuli for these men, the sexual arousal possible in partnered sex may be sufficient for achieving an erection (especially if paraphilic fantasies are used), but not a coital orgasm (1).

Most of these concepts are speculative and amenable to empirical verification. As a matter of fact, some of the available questionnaire studies indicated a higher degree of hostility and anxiety in patients with DE (38). However, these studies had methodological limitations (1).

The role of distress in the concept of ejaculatory dysfunction

Psychological distress is a range of symptoms and experiences of a person's internal life that are commonly held to be troubling, confusing, or out of the ordinary (5).

In DSM-IV, a criterion was added in the sense that PE caused marked distress or interpersonal consequences before it could be diagnosed as PE (39). DSM-5 has kept the existence of distress on the sufferer as a mandatory diagnosis criterion for DE and PE, and states that these sexual disorders may also cause personal distress in the sexual partner and decreased sexual satisfaction for the couple (5).

Some studies have found distress to be associated with PE and that PE can be associated with negative psychological consequences for patients and their partners (13,40,41). There is a debate about the choice of words to describe these negative psychological consequences. Qualitative research used in the development of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) for pharmaceutical research indicates that words such as bother, frustration, and annoyance reflect more accurately patient experiences (42). A more important issue is whether the negative consequence of a disorder should be included in the definition of the diagnostic entity. For example, one could argue that the entity of PE should be defined simply in terms of IELT. Waldinger cogently makes this argument by using an analogy of a migraine headache. A migraine headache is diagnosed by its clinical presentation, not by the amount of distress it causes to the patient (43). Among the diagnosis criteria for PE, DSM-5 ultimately adopted the existence of distress in cases in which “a persistent or recurrent pattern of ejaculation occurring during partnered sexual activity within approximately 1 minute following vaginal penetration and before the individual wishes it”. However, for DE, the DSM-5 states that, in addition to the existence of distress, “the definition of ‘delay’ does not have precise boundaries, as there is no consensus as to what constitutes a reasonable time to reach orgasm or what is unacceptably long for most men and their sexual partners” (5).

Jern et al. aimed to clarify the relationship between a number of indicators of PE and personal distress. In order to do this, they looked at differences in experienced distress as a function of the level of the different indicator variables. The levels of the indicator variables evidence could be a cut-off point with those scoring below and those scoring above this point having different levels of personal distress; such cut-off scores could represent a potential way to separate different degrees of severity of PE. The authors found that every indicator of PE included—ejaculation prior to intercourse, feeling of control, worrying about PE, pretending to ejaculate, trying to speed up intercourse, trying to delay intercourse, subjective experience of PE, later ejaculation than desired, and the number of thrusts—was significantly associated with sexual distress. However, there were substantial differences between the different indicator variables. First (and perhaps foremost), there was a substantial variation in effect sizes for the different indicators, with variables measuring subjective experience related to PE having a substantially stronger impact on the variance in sexual distress. Among men in a relationship, a low number of thrusts and a short ejaculation latency time were related to sexual distress, whereas no such association was found for participants who were not in a relationship. One could argue that these factors are particularly embarrassing in a relationship where the man is repeatedly engaged with the same partner, compared with the relative anonymity of one-night stands. The authors also found that nearly 85% of the variance in sexual distress is caused by something other than PE (general psychological distress in the individual, such as anxiety or depression). The direction of causality is not established: they cannot be certain whether anxiety and worry is causing PE or if PE is causing the anxiety (44).

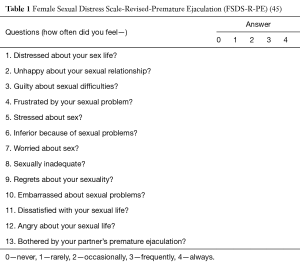

Although the effects of PE on the partner in terms of distress are essential to understanding the impact of PE on the men and couples, this topic has been understudied using validated instruments. Limoncin et al. undertook the first population based study to specifically investigate the relationship between PE and sexual distress in the female partner. The Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised-Premature Ejaculation (FSDS-R-PE) questionnaire was validated and standardized in a population of women whose partners had PE. The FSDS-R-PE is a self-reporting questionnaire that includes thirteen questions that ask women to rate their distress in relation to low sexual desire (Table 1) (45).

This questionnaire (FSDS-R-PE) showed that the female partners of men with PE experienced significantly higher sexual distress than controls. After adjusting for confounders such as age, relationship duration and educational level, there was a significant association between female sexual distress and male partners with PE. The fact that the perception of sexual distress did not differ across age groups and was not influenced by relationship duration or educational level constitutes further interesting evidence. The high sensitivity and specificity makes this questionnaire an important tool, and a useful, powerful psychometric instrument to identify female sexual distress related to a partner with PE (45).

Subsequently, a study undertaken with women living in Mexico, Italy, and South Korea showed that the perception of PE and related distress had a strong variation and depended not only on their own sexual functioning but also on their views of what good and fulfilling sexuality meant. In this regard, an important source of distress is not only the parameters related to performance such as control or duration, but rather inappropriate attention focus possibly due to lack of control and the negligence of sexual needs and preferences other than penetration (2).

The role of anxiety in ejaculatory dysfunction

Multiple life stressors can lead to anxiety and in turn induce male and female sexual dysfunction. Psychosocial stress factors are part of everyday life. In addition to life stressors resulting in anxiety, sexual dysfunction itself can lead to specific anxiety (16), anxiety stemming from a man’s lack of confidence to perform adequately, to appear and feel attractive (body image), to satisfy his partner sexually, and to experience an overall sense of self-efficacy (46).

Anxiety is used to characterize three different mental phenomena: (I) a phobic response; (II) the end result of conflict resolution where two contradictory urges are at play; (III) anticipatory anxiety (preoccupation with sexual failure and poor performance leads to deteriorating the sexual function and avoidance of future sexual interactions) (17,47,48). Anxiety related to sexual relations in men with PE is 30.7% compared to 7.7% in subjects without PE (49).

The relationship between any type of anxiety disorders and male sexual dysfunction has not been studied. Indeed, anxiety is a common feature of PE and, while there is some evidence that this may also be a reason for the condition, it is certainly likely to be a consequence (50).

The association between pre-existing anxiety disorders and sexual performance anxiety has been found in men and couples with ejaculatory dysfunction. This could reflect a process in which pre-existing anxiety triggers sexual dysfunction, causing performance anxiety and leading to a vicious cycle: anxiety, sexual dysfunction, more anxiety (51).

It is important to bear in mind that performance anxiety per se does not generally cause the initial episode of PE. It is responsible for maintaining the dysfunction, because it distracts the man from focusing on his level of arousal, rendering him helpless in exerting voluntary control over his sexual arousal and ejaculation (17). With each failure, performance anxiety increases and may result in a behavior of sexual avoidance (18). Men believe that their partners do not understand the frustration and humiliation that they experience. This disconnection between men and their partners is the basis for considerable relationship tension (17).

Life event stressors may precipitate PE presumably due to a temporary imbalance of the neurological mechanisms of ejaculation. In some cases, PE may result from situational stress, whereas in other cases it is unclear whether the identified anxiety may be the cause or sequelae of PE (52).

The most distressing form of ejaculation dysfunction is lifelong and generalized PE with very short latency times (<30 s). It has been associated with higher social anxiety and with a stronger tendency to avoid aversive situations. In turn, a situational form of PE is characterized by a somewhat different type of anxiety that is an emotionalism responsible for the variations of the problem according to affective and relational circumstances (53).

As already mentioned in relation to the etiology of DE, most of the concepts are highly speculative and amenable to empirical verification. As a matter of fact, some studies have indicated a higher degree of anxiety in these patients (54,55). It has been suggested that the evaluative aspect of sex with a partner often creates “sexual performance anxiety” for the man, a factor that may contribute to DE. Such anxiety typically stems from the man’s lack of confidence to perform adequately, to appear and feel attractive (body image), to satisfy his partner sexually, to experience an overall sense of self-efficacy, and to measure up against the competition (46,56). Additionally, anxiety surrounding the inability to ejaculate may draw the man’s attention away from erotic cues that normally serve to enhance arousal (31). However, studies do not allow a clear interpretation regarding the cause and consequence status of the conditions (1).

In summary, experience suggests that anxiety disorders are related to sexual dysfunction in men and women. Several sexually dysfunctional individuals exhibit heightened levels of anxiety, suggesting an essential role of this condition in the subjective experience and maintenance of sexual disorders. But this does not imply causality. In addition, it is not clear either if it is generalized anxiety, or anxiety that is more closely related to the sexual content that is more strongly related to sexual dysfunction (16).

Longitudinal and experimental studies are needed to address whether anxiety causes sexual dysfunction, whether sexual dysfunction causes anxiety, whether the relationship is bidirectional and reciprocating, or anxiety and sexual dysfunction can be different expressions of the same processes (16).

The burden of ejaculatory dysfunction for the patient

Often the impact of DE is not fully appreciated by some clinicians. They erroneously perceive this dysfunction as a positive attribute that allows the man to “bestow multiple coital orgasms to his partner” (35).

A distinguishing characteristic of men with DE is that they usually have little or no difficulty attaining or keeping their erections. Yet, despite their satisfactory erections, they report low levels of subjective sexual arousal and pleasure, at least compared with sexually functional men (30). It is not frequent for men with DE to “fake orgasm”. They perceive it as a demand from their partner to reach orgasm (35). Consequently, high levels of relationship distress, fear of failure, sexual dissatisfaction, anxiety regarding their sexual performance and general health issues are significantly higher in DE men than in sexually functional men (24,30).

Jannini et al. perceive the delay in ejaculation as mirroring the man’s over-controlled personality organization. In other words, in life these men show little emotion and seem over-controlled. Additionally, the authors suggest a possible role of the man’s fear of impregnating his partner or contracting sexually transmitted diseases as interfering with arousal and ejaculation (57).

Men with DE are similar to men with other sexual dysfunctions. They exhibit the same elevated level of sexual dissatisfaction and they also show lower levels of coital frequency. They use masturbatory activity to a lower extent relative to controls (28).

The burden of PE for patients is revealed in three different levels: the emotional burden; the health burden; and the burden on the relationship (58). In terms of emotional burden, there is often a sense of embarrassment and shame for not being able to satisfy their partners and patients often have low self-esteem, feelings of inferiority (59), anxiety, anger, and disappointment. Men feel frustrated about their PE and how it affects their intimacy with their partners and sexual relationship (60). These dysfunctional men report lower rates of general life satisfaction than controls (61). Additionally, PE durations extending beyond a year elevate the risk of depression in PE patients (62).

Men with PE are more likely to report being dissatisfied with their sexual relationship than men without PE (49), and coital frequency is significantly lower (63). They often find it hard to initiate or maintain relationships. These patients may not believe that they are giving adequate sexual satisfaction and find it easier to cheat on their partners as they perceive that their partners are not being true about their feelings (58).

The burden of ejaculatory dysfunction on the partner and the relationship

The definitions of PE take into consideration different aspects of this condition, including lack of control over ejaculation (5,64,65), persistency (64), latency time (5,64,65), distress (5,64,66), sexual satisfaction (64,65) and interpersonal difficulty (64). Some definitions emphasize the importance of these effects on the partner as well as the patient, although effects on partners have been less studied (4).

Patrick et al. reported that 44% of partners of men with PE rated their extent of personal distress as “quite a bit” or “extreme” compared to 3% in a group of partners of normal controls (4). Subsequently, Burri et al. indicated that women in the PE group had a 7.12 to 9.83 greater probability of having sexual distress than controls (2). Although partner distress appears as a significant contributor to treatment seeking behavior, there are limited data regarding the effects of PE on partners.

It is important to highlight that women and men commonly have more than one sexual dysfunction when they seek treatment. Consequently, for the small, but significant number of women who reported having their own problem irrespective of their partner’s PE, treatments for PE may have no impact or even detrimental impact on the female partner’s condition (67).

Many factors are thought to influence sexual functioning in women including age, race, education, physical and emotional health and menopause symptoms (68-70). Another factor could be the sexual dysfunction of the male partner (67).

Research on the partners of men with PE has received less attention than that research on female partners of men with erectile dysfunction (ED). However, the literature suggests that, as is the case with the partners of men with ED, PE partners will also have increased levels of sexual difficulties, as already mentioned (67).

An illustration is the fact that there is some evidence to suggest that partnered-orgasm frequency is associated with the duration of penile-vaginal intercourse, rather than, as is often written, correlating with the duration of foreplay (71). PE had a particularly high occurrence in the partners of women presenting sexual desire disorder (29.9%), arousal/lubrication disorder (42.7%), anorgasmia (47.8%) and not enjoying sex (51.5%) (72). Hobbs et al. confirmed that partners of men with PE reported 77.7% sexual dysfunction compared with 42.7% for partners of men with no sexual dysfunction. Additionally, nearly half (48.2%) of the women whose partners had PE experienced two or more sexual dysfunctions, compared to only 22.4% of the control group (67). Similar results were reported by Kaya et al. who found sexual dysfunction in 78% of women who had a male partner with PE, while on the other hand sexual dysfunction was 40% for female partners of healthy men (73).

Naturally, the woman’s sexual dysfunction cannot be attributed to the man’s PE alone; there will be other factors involved (67). High prevalence of female sexual dysfunction, in these studies, may reflect the existence of sexual dysfunction in the women themselves or could be indicative of greater difficulty with their own desire, arousal and satisfaction resulting directly from the presence of PE in their partners. It is also possible that the focus of dissatisfaction is not physiological but has much more to do with a frustration with the lack of connection and sense of impaired intimacy resulting from the male partner’s preoccupation with PE and his sexual performance (67).

Some studies have indicated that the effects of PE on the female partner are essential in order to understand the effects of PE on the male partner and on the sexual relationship as a whole (52,59,74). Patrick et al. demonstrated that PE similarly and adversely affects the female partner and the male with PE. Although partner perceptions of PE generally indicated less dysfunction than those of subjects, partner outcome measures play an important part in the assessment of PE (4). Additionally, few differences in outcome measures were observed between the lifelong and acquired PE groups. The better ratings of satisfaction with sexual intercourse and lower ratings of interpersonal difficulty observed in the lifelong PE group suggest that different aspects of PE may be of greater importance at different times in the natural history of the dysfunction (4).

In their turn, personal anguish, decreased intimacy, relationship stress and dissatisfaction can result from DE (75-77). Along with other sexually dysfunctional counterparts, men with DE typically report a lower frequency of intercourse (28).

Some authors focus on the men’s idiosyncratic masturbatory style that cannot be replicated with a female partner using her hand, mouth, or vagina (28,37,78). Many men with DE engage in self-stimulation that is striking in the speed, pressure, duration, location and intensity necessary to produce an orgasm, and dissimilar to what they experience with a partner (24). Apfelbaum suggests that men presenting with DE may actually possess an “autosexual” orientation in that they experience greater enjoyment in solo masturbation, rather than partnered sex (37). Perelman argues that masturbation serves as a “dress rehearsal” for sex with a partner. By informing the patient that his difficulty is merely a reflection of “not rehearsing the part he intended to play”, the stigma associated with this problem can be minimized and cooperation of both the patient and partner can be evoked (24).

A man’s (expressed/unexpressed) anger toward his partner may be an important intermediate causational factor: anger acts as a powerful anti-aphrodisiac, and while some men avoid sexual contact entirely when angry at a partner, others attempt to perform, only to find themselves only modestly aroused and unable to maintain an erection and/or reach orgasm (24).

Conclusions

Ejaculatory dysfunction has a significant negative impact on both the man and his female partner and, consequently, has implications for the couple as a whole.

These dysfunctions involve the integration of physiological, psychobehavioral, cultural, and relationship dimensions. All these elements need to be considered in the treatment of these conditions.

Treatment is most effective when the etiology of ejaculatory dysfunction is properly identified and tailored to address the pathophysiology.

Although partner perceptions of PE generally indicated less dysfunction than those of subjects, partner outcomes measures play a part in the assessment of PE.

Therapeutics approaches not only improved latency time, but also both men and their partners had a significantly improved sexual satisfaction, with partners experiencing an improvement in coital orgasmic attainment.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Hartmann U, Waldinger MD. Treatment of delayed ejaculation. In: Leiblum SR, Rosen RC, editors. Principles and practice of sex therapy. 4th ed. New York, NY: The Guildford Press, 2007:241-76.

- Burri A, Giuliano F, McMahon C, et al. Female partner's perception of premature ejaculation and its impact on relationship breakups, relationship quality, and sexual satisfaction. J Sex Med 2014;11:2243-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCarthy B, McCarthy E, editors. Male sexual awareness. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1998.

- Patrick DL, Althof SE, Pryor JL, et al. Premature ejaculation: an observational study of men and their partners. J Sex Med 2005;2:358-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- Waldinger MD. The neurobiological approach to premature ejaculation. J Urol 2002;168:2359-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Althof SE, Abdo C, Dean J, et al. International Society for Sexual Medicine's Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 2010;7:2947-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hatzimouratidis K, Amar E, Eardley I, et al. Guidelines on male sexual dysfunction: Erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation. Eur Urol 2010;57:804-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carson C, Gunn K. Premature ejaculation: Definition and prevalence. Int J Impot Res 2006;18:S5-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR, 4th edition, Text Revised, Washington, DC: America Psychiatric Publishing, 2000.

- Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, et al. Sexual problems among women and men aged 40-80 y: prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Int J Impot Res 2005;17:39-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281:537-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Porst H, Montorsi F, Rosen R, et al. The premature ejaculation prevalence and attitudes (PEPA) survey; prevalence, comorbidities, and professional help-seeking. Eur Urol 2007;51:816-23; discussion 824. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Althof SE, McMahon CG, Waldinger MD, et al. An update of the International Society of Sexual Medicine's guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of premature ejaculation (PE). J Sex Med 2014;11:1392-422. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Byers ES, Rehman U. Sexual well-being. In: Tolman D, Diamond L, editors. APA handbook of sexuality and psychology Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2013:317-37.

- Brotto L, Atallah S, Johnson-Agbakwu C, et al. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. J Sex Med 2016;13:538-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Althof S. Psychological approaches to the treatment of rapid ejaculation. J Mens Health Gend 2006;3:180-6. [Crossref]

- Abdo CH. The psychodynamic approach to premature ejaculation. In: Jannini EA, McMahon C, Waldinger MD, editors. Premature ejaculation: From etiology to treatment. Milan: Springer, 2012:221-7.

- Abraham K. Ejaculatory praecox. In: Jones E, editor. Selected papers of Karl Abraham. London: Hogarth Press, 1949.

- Schapiro B. Premature ejaculation, a review of 1,130 cases. J Urol 1943;50:374-9.

- Kaplan H, editor. The new sex therapy: Active treatment of sexual dysfunctions. New York: Crown, 1974.

- Kaplan H, editor. PE: How to overcome premature ejaculation. New York: Bruner/Mazel, 1989.

- Hartmann U, Schedlowski M, Krüger TH. Cognitive and partner-related factors in rapid ejaculation: Differences between dysfunctional and functional men. World J Urol 2005;23:93-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA, Rowland DL. Retarded ejaculation. World J Urol 2006;24:645-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Witt MA, Grantmyre JE. Ejaculatory failure. World J Urol 1993;11:89-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Master VA, Turek PJ. Ejaculatory physiology and dysfunctions. Urol Clin North Am 2001;28:363-75, x. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vale J. Ejaculatory dysfunction. BJU Int 1999;83:557-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowland D, Van Diest S, Incrocci L, et al. Psychosexual factors that differentiate men with inhibited ejaculation from men with no dysfunction or with another dysfunction. J Sex Med 2005;2:383-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morokoff PJ, Heiman JR. Effects of erotic stimuli on sexually functional and dysfunctional women: Multiple measures before and after treatment therapy. Behav Res Ther 1980;18:127-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowland DL, Keeney C, Slob AK. Sexual response in men with inhibited or retarded ejaculation. Int J Impot Res 2004;16:270-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. A new combination treatment for premature ejaculation: A sex therapist’s perspective. J Sex Med 2006;3:1004-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Binik YM, Hall KS. Delayed ejaculation. In: Perelman MA, editor. Principles and practice of sex therapy. 5th ed. New York: The Guilford Press, 2014:138-55.

- Waldinger MD. Toward evidence-based genetic research on lifelong premature ejaculation: a critical evaluation of methodology. Korean J Urol 2011;52:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sadowski DJ, Butcher MJ, Köhler TS. Delayed ejaculation: Medical and psychological treatments and algorithm. Curr Sex Health Rep 2015;7:170-9. [Crossref]

- Althof SE. Psychological interventions for delayed ejaculation/orgasm. Int J Impot Res 2012;24:131-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. Masturbation revisited. Contemporary Urology 1994;6:68-70.

- Apfelbaum B. Retarded ejaculation: A much-misunderstood syndrome. In: Lieblum SR, Rosen RC, editors. Principles and practice of sex therapy: Update for the 1990’s. 2nd edition. New York: Guilford Press, 1989:168-206.

- Dekker J. Inhibited male orgasm. In: O’Donohue W, Geer JH, editors. Handbook of sexual dysfunctions: Assessment and treatment. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1993.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV, 4th edition, Washington, DC: America Psychiatric Publishing, 1994.

- McMahon CG. Clinical trial methodology in premature ejaculation. Observational interventional and treatment preference studies — part I — Defining and selecting the study population. J Sex Med 2008;5:1805-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowland DL, Motofei IG. The aetiology of premature ejaculation and the mind-body problem: Implications for practice. Int J Clin Pract 2007;61:77-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Althof S, Rosen R, Symonds T, et al. Development and validation of a new questionnaire to assess sexual satisfaction, control and distress associated with premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 2006;3:465-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD. Premature ejaculation: Different pathophysiologies and etiologies determine its treatment. J Sex Marital Ther 2008;34:1-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jern P, Santtila P, Johansson A, et al. Indicators of premature ejaculation and their associations with sexual distress in a population-based sample of young twins and their siblings. J Sex Med 2008;5:2191-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Limoncin E, Tomassetti M, Gravina GL, et al. Premature ejaculation results in female sexual distress: standardization and validation of a new diagnostic tool for sexual distress. J Urol 2013;189:1830-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zilbergeld B, editor. The new male sexuality. New York: Bantam Books, 1993.

- Kaplan HS. Anxiety and sexual dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry 1988;49 Suppl:21-5. [PubMed]

- Strassberg DS, Kelly MP, Carroll C, et al. The psychophysiological nature of premature ejaculation. Arch Sex Behav 1987;16:327-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowland D, Perelman M, Althof S, et al. Self-reported premature ejaculation and aspects of sexual functioning and satisfaction. J Sex Med 2004;1:225-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD. Lifelong premature ejaculation: From authority-based to evidence-based medicine. BJU Int 2004;93:201-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar RP, Kumaran AK. The association of anxiety with the subtypes of premature ejaculation: a chart review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2014.16. [PubMed]

- Metz ME, Pryor JL. Premature ejaculation: a psychophysiological approach for assessment and management. J Sex Marital Ther 2000;26:293-320. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kempeneers P, Andrianne R, Bauwens S, et al. Functional and psychological characteristics of Belgian men with premature ejaculation and their partners. Arch Sex Behav 2013;42:51-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Hamid IA. Saleh el-S. Primary lifelong delayed ejaculation: characteristics and response to bupropion. J Sex Med 2011;8:1772-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xia JD, Han YF, Pan F, et al. Clinical characteristics and penile afferent neuronal function in patients with primary delayed ejaculation. Andrology 2013;1:787-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Althof SE, Leiblum SR, Chevert-Measson M, et al. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. In: Lue TF, Basson R, Rosen R, et al, editors. Sexual medicine: sexual dysfunctions in men and women, Second International Consultation on Sexual Dysfunctions. Paris, France: 2004:73-116.

- Jannini EA, Simonelli C, Lenzi A. Sexological approach to ejaculatory dysfunction. Int J Androl 2002;25:317-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sotomayor M. The burden of premature ejaculation: the patient's perspective. J Sex Med 2005;2 Suppl 2:110-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Symonds T, Roblin D, Hart K, et al. How does premature ejaculation impact a man’s life? J Sex Marital Ther 2003;29:361-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Revicki D, Howard K, Hanlon J, et al. Characterizing the burden of premature ejaculation from a patient and partner perspective: a multi-country qualitative analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCabe MP. Intimacy and quality of life among sexually dysfunctional men and women. J Sex Marital Ther 1997;23:276-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Gao J, Liu J, et al. Prevalence rate and risk factors of depression in outpatients with premature ejaculation. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:317468.

- Rowland DL, Patrick D, Rothman M, et al. The psychological burden of premature ejaculation. J Urol 2007;177:1065-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serefoglu EC, McMahon CG, Waldinger MD, et al. An evidence-based unified definition of lifelong and acquired premature ejaculation: report of the second International Society for Sexual Medicine Ad Hoc Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation. J Sex Med 2014;11:1423-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. ICD-10 1992;1:355-6.

- Montague DK, Jonathan J, Broderick G, et al. AUA guideline on the pharmacologic management of premature ejaculation. J Urol 2004;172:290-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hobbs K, Symonds T, Abraham L, et al. Sexual dysfunction in partners of men with premature ejaculation. Int J Impot Res 2008;20:512-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hisasue S, Kumamoto Y, Sato Y, et al. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction symptoms and its relationship to quality of life: a Japanese female cohort study. Urology 2005;65:143-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, Kim SC, et al. Sexual behaviour and dysfunctions and help seeking patterns in adults aged 40-80 years in the urban population of Asian countries. BJU Int 2005;95:609-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdo CH, Oliveira WM, Moreira ED, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and correlated conditions in a Sexual dysfunction in PE partners sample of Brazillian women—results of the Brazillian study on sexual behaviour (BSSB). Int J Impot Res 2004;16:160-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weiss P, Brody S. Women's partnered orgasm consistency is associated with greater duration of penile-vaginal intercourse but not of foreplay. J Sex Med 2009;6:135-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Riley A, Riley E. Premature ejaculation: presentation and associations. An audit of patients. Int J Clin Pract 2005;59:1482-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaya C, Gunes M, Gokce AM, et al. Is sexual function in female partners of men with premature ejaculation compromised? J Sex Marital Ther 2015;41:379-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Byers ES, Grenier G. Premature or rapid ejaculation: heterosexual couples’ perceptions of men’s ejaculatory behavior. Arch Sex Behav 2003;32:261-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bronner G, Ben-Zion IZ. Unusual masturbatory practice as an etiological factor in the diagnosis and treatment of sexual dysfunction in young men. J Sex Med 2014;11:1798-806. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowland D, McMahon CG, Abdo C, et al. Disorders of orgasm and ejaculation in men. J Sex Med 2010;7:1668-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shin DH, Spitz A. The evaluation and treatment of delayed ejaculation. Sex Med Rev 2014;2:121-33. [Crossref]

- Perelman M. Idiosyncratic masturbation patterns: A key unexplored variable in the treatment of retarded ejaculation by the practicing urologist. J Urol 2005;173:S340.