Psychosexual therapy for delayed ejaculation based on the Sexual Tipping Point model

Introduction

The Sexual Tipping Point® (STP) model facilitates understanding, diagnosis and treatment of delayed ejaculation (DE). DE is a subset of male ejaculatory disorders (EjD) and a type of diminished ejaculation disorder (DED), which including all subtypes manifesting ejaculatory delay/absence (1). Healthcare clinicians (HCC) may find DE difficult to treat and may not grasp the interpersonal and psychological distress it causes. A single pathogenetic pathway does not exist for sexual disorders generally and the same is true for DE specifically (2). Assessment requires a thorough sexual history including inquiry into masturbatory methods to ascertain the information needed for proper diagnosis and treatment (3,4). This article derives from 40 years of clinical experience (>300 DE cases) and describes a transdisciplinary approach to the etiology, diagnosis and treatment of men with DE based on the STP model [see (A) in section “Notes”] (5-7).

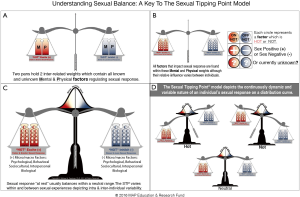

The STP is the interaction of constitutional sexual capacity with various bio-psychosocial-behavioral and cultural factors. A person’s STP differs from one experience to another, based on the proportional effect of one factor(s) dominating, as others recede in importance. The STP model can illustrate such intra and inter-individual variability characterizing sexual response and its disorders for both men and women (Figure 1).

The STP can be easily used to explain etiology and highlight treatment targets for patients. It helps clinicians disabuse patient’s erroneous binary beliefs. HCCs can instill hope through a simple explanation of how the problem’s causes can be diagnosed, parsed, and “fixed” (2). Teaching the STP model to the patient and partner helps reduce despair and anger. A complaint of DE might evoke this dialogue: “Your DE is not ‘all in your head’” nor “is it all a physical problem.” Reciprocally, his partner can be taught the reasons are not, “all your fault at all!”

Prevalence & characterization

DE remains an uncommon disorder, with estimated prevalence rates of 1–4% of the male population (9,10), but rates are increasing due to greater use of pharmacotherapy [5-alpha reductase inhibitors (5αRIs), serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs), etc.], in addition to an aging population’s gradually declining ejaculatory capacity (8,11,12). A man complaining of DE usually has intact erectile capacity, but his ability to ejaculate during partnered sex is extremely difficult, or impossible, despite “adequate” stimulation (8). Ejaculatory difficulty may occur in all situations (generalized) or limited to certain experiences (situational). It may be lifelong (primary) or acquired (secondary). A man typically reports an inability to ejaculate in the presence of a partner (especially during coitus), but has little difficulty reaching orgasm and ejaculation during solo masturbation.

The negative impact described in the ED and PE literature also applies to men with DE, in terms of relationship distress, anxiety over sexual performance, and general health issues, versus sexually functional men. Men with DE typically report less coital activity, lower subjective arousal, and often report feeling “less of a man” (2,8,13-15). Some partners initially enjoy extended intercourse, but eventually they usually experience some annoyance, pain, injury, and the very distressing question: “Does he really find me attractive?” Despite initially blaming themselves, partners frequently become angry at the perceived rejection. Men with DE may fake orgasm to avoid negative partner reaction (8). Finally, distress is extreme when conception “fails”, while fear of pregnancy leads other men to avoid sex altogether (8,16,17).

Definition

Some nomenclature confusion arises over ejaculation and orgasm usually occurring simultaneously, despite being separate physiological phenomena. Orgasm is typically coincident with ejaculation, but is a central sensory event that has significant subjective variation. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes for DE diagnosis is: N53.11—retarded ejaculation. Sexual dysfunction not due to a substance or known physiological condition is diagnosed as F52.32—male orgasmic disorder. In the United States (particularly among mental health practitioners), many rely on the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), which defines DE (302.74) as: marked delay in ejaculation and/or marked infrequency or absence of ejaculation. Five additional factors must be considered during assessment: (I) partner issues; (II) relationship quality; (III) individual vulnerability; (IV) cultural/religious influences; and (V) medical diagnoses relevant to prognosis (2,18).

The International Society of Sexual Medicine (ISSM) recommends using “evidence-based” definitions of EjD. The 2008 International Society for Sexual Medicine Ad Hoc Committee for the definition of PE defined lifelong PE (19,20). The 2nd International Society for Sexual Medicine Ad Hoc committee defined acquired PE (21,22). Amongst other sources, these two committees (and subsequent International Consultations for Sexual Medicine) relied upon Patrick, and Waldinger et al.’s published “worldwide” normative IELT studies that provided evidence that heterosexual males in stable monogamous relationships had a median IELT duration of approximately 5–6 minutes: (I) “…The distribution of the IELT in all the five countries was positively skewed, with a median IELT of 5.4 minutes (range, 0.55–44.1 minutes)” (23) (p. 492); (II) “The IELT had a positively skewed distribution, with a geometric mean of 5.7 minutes and a median of 6.0 minutes (range: 0.1–52.1 minutes)” (24) (p. 2888). In addition to the Waldinger et al. studies, the Patrick et al. [2005] study was also cited by the 3rd International Consultation On Sexual Medicine (ICSM) Committee on Disorders of Male Orgasm and Ejaculation as supporting, “that most sexually functional men ejaculate within about 4–10 minutes” (25,26) (p. 861).

Influenced by those population studies, the ISSM EjD’s definitions invoked a concept of percentage (0.5% and 2.5%), often used in medicine when defining disease (24,27,28). The 3rd ICSM’s defined DE as an IELT threshold beyond 20–25 minutes of sexual activity, as well as negative personal consequences such as bother or distress. The 20–25 minutes IELT criterion was chosen because it represents greater than two standard deviations above the mean found in the IELT population based studies which helped form the basis for earlier ISSM EjD definitions (21,23,24,28).

An alternative perspective regarding the temporal criterion emerges when recognizing that the ISSM EjD definitions were all based on studies which documented that the majority of men (~65%) had an IELT range of approximately 4–10 minutes (19,20,22,29). Any skeptical readers should be reassured as to the accuracy and reliability of that ~4–10 minute IELT range calculation [see (B, C) in section “Notes”], when reminded that the 3rd ICSM committee on Disorders of Male Orgasm and Ejaculation report also indicated: “…most sexually functional men ejaculate within about 4–10 minutes (21).” Such robust quantitative evidence should become the basis for determining the temporal criterion for defining PE and DE [see (D) in “Notes” section]. Any bilateral deviation from the majority of men’s ~4–10 minutes IELT range would meet the qualification for the temporal criterion, but a licensed HCC must also assess for “lack of control” and “distress” for a man to be diagnosed with a PE or DE disorder (19,20,22,29).

Using the “middle” values of a “normal range” of ejaculatory time as a cut-off point for both PE and DE in terms of the definitive temporal construct (rather than the “tails”) was consistent with the reality that disorders of orgasm and ejaculation represented a spectrum from dysfunction, to function, to dysfunction once again. A more relaxed screening standard implicitly recognized etiological variability and multidimensionality, which can become overshadowed when dysfunction is over-defined because of latency time. Elegantly, the same temporal screening standard would apply to lifelong and acquired PE, as well as DE.

Loosened latency criteria could result in false positive diagnoses, but requiring a licensed HCC evaluation of the control and distress criteria reduced that risk. This author believes “control” and “distress” trump “latency” and should carry greater diagnostic weight. There is substantial evidence that satisfactory sexual intercourse and the distress related to both PE and DE are probably mediated more by perceived control over ejaculation than by latency time (30-33). Jern et al. have emphasized how the concept of “control” (self-efficacy, confidence, etc.) does not correlate perfectly with IELT, and is mitigated by volition (34).

Below is this author’s definition of coital DE, as men most typically pursue treatment for that subtype.

Coital DE is defined as:

- Inability/incapacity to choose to ejaculate intra-vaginally in less than ~10 minutes, in all, or nearly all, coital encounters;

- Not having the ability/capacity to choose to ejaculate sooner, but preferring to do so;

- Experiencing negative personal consequences, such as distress, bother, frustration and/or the avoidance of sexual intimacy.

Similar to the ISSM recommendations, the definition would be further qualified as lifelong (primary) or acquired (secondary), global or situational. Analogous to DSM 5 definitions would then be specified as mild, moderate, or severe. It must be emphasized that the preceding conceptualization of how both PE and DE could be redefined does not mean that everyone outside the 4–10 minutes IELT range would be diagnosed with a sexual disorder. Only those men who met the temporal criterion and were also suffering from distress and an incapacity/inability to choose when he wanted to ejaculate would potentially be diagnosed with a disorder. For instance, a man who usually ejaculates in 3 minutes, who is not distressed would not be labeled PE, nor would a man who ejaculates in 15 minutes who is not distressed be labeled DE. Clearly a man and/or his partner might prefer that coitus is longer than 10 minutes, and such an individual is not suffering from DE. However, a man who is unable to ejaculate within ~4–10 minutes (IELT) consistent with the majority other men (~65%), and subjectively experiences “no choice” (control) and is distressed, could be diagnosed as suffering from DE [see (E) in section “Notes”].

Etiology

A man’s inability to implement any strategy to facilitate ejaculating in response to coital stimulation within an ~4–10 minutes time frame may be due to biological and/or a range of psychosocial and cultural factors (5,15). As biological causes of DE are reviewed elsewhere in this journal, this article focuses on psychosocial-behavioral and cultural causes. However, medical examination, laboratory testing and sexual history to rule out anatomical, hormonal, neurological abnormalities which may result in DE, should be obtained for every patient whenever possible. However, physicians often tell DE patients they are “normal”.

Certainly, there is significant pre-clinical research indicating the importance of biological predisposition in EjD. Genetically predetermined ejaculatory thresholds do have a prodigious impact on ejaculatory ease and latency time, and distribute similarly to other human characteristics (5,35). Yet, scatter clouds rather than trigger points are better metaphors for ejaculatory threshold. The timing of a particular ejaculation is the result of a variety of psychosocial-cultural and behavioral factors influencing that biologically predetermined range (10). Such a multilayered conceptualization is different from current animal models that postulate an exclusive neurobiological threshold model (36). Yet, the very nature of genetic predisposition and its manifestations are variable. A man whose IELT is greater than 35 minutes may be suffering from DE that is primarily biological in its etiology, secondary to genetic predisposition, disease or pharmaceutical side effects. However, this DOES NOT mean that a man who always ejaculated in approximately 18–20 minutes, who manifests an “inability to choose” to ejaculate sooner, and feels distressed, is not also suffering as much, or even more than his greater than ~35 minutes IELT counterpart. Such a man should be diagnosed with a life-long (primary) DE even if his bio-psychosocial-cultural factors are not yet fully comprehended. Nosology and etiology are related but separate constructs. Presumably he suffers from a susceptibility that interacted with a variety of psychosocial, environmental, cultural and medical risk factors resulting in dysfunction (5,7).

Although a biopsychosocial model is the ideal lens to view etiology, there is benefit from reviewing the earlier psychological and behavioral theories which variously emphasized ineffective sexual communication, cultural and religious prohibitions, mood disorders, fatigue, trauma, and feeling overly pressured to have sex. Dynamics reported included: losing control, abandonment/rejection, intimacy, autonomy, hostility, and paraphilic inclinations/interests (2,37,38). Fear of: hurting/defiling partner, female genitalia have all been discussed. Other commonly invoked psychosocial factors were: “spectatoring” (intrusive self-observation during sex), relational conflict, and pregnancy fears (39). Additional presumed causes of DE included: anxiety, lack of confidence, poor body image, etc. (10). Anxiety draws the man’s attention away from erotic cues that enhance arousal, and interfere with genital stimulation sensation resulting in insufficient excitement for climax, even if erection is maintained. Depression can lead to DE as it is the most important clinical condition affecting sexual desire; this relationship is bidirectional (40). Although medications for depression may affect desire through shared underlying mechanisms, studies have demonstrated that depression itself may have a more significant adverse effect on desire and orgasmic capacity than anti-depressant medication side effects (40-43).

Apfelbaum identified men who preferred solo masturbation to partnered sex as having an “autosexual orientation” (44,45). Subsequent work supported his observations that these men often present due to partner pressure (10,17). Perelman documented DE cases caused by men confusing ED medication induced vasocongestion, with genuine sexual arousal (12).

Regardless of the degree of organic etiology, DE is exacerbated by insufficient stimulation: an inadequate combination of “friction and fantasy” (8). Fantasy refers to all erotic thoughts and feelings that are associated with a given sexual experience. High frequency negative thoughts may neutralize or override erotic cognitions (fantasy) and subsequently delay, ameliorate or completely inhibit ejaculation, while a partner’s physical stimulation (friction) may result in unsatisfying/inadequate physical stimulation. Perelman identified three masturbation related factors associated with DE: frequency of masturbation (>3 times per week); idiosyncratic masturbatory style, and adisparity between masturbatory fantasy and reality (4,46). Although correlated with high frequency masturbation, the primary factor causing DE for many men was an “idiosyncratic masturbatory style”, which Perelman defined as masturbation technique not easily duplicated by the partner’s hand, mouth, or vagina. These men were engaging in patterns of self-stimulation notable for one or more of the following idiosyncrasies: speed, pressure, duration, body posture/position, and specificity of focus on a particular “spot” in order to produce orgasm/ejaculation (4). In fact, some men report penile irritation and erythema secondary to their masturbatory pattern (13,47). Almost universally, these men fail to communicate their preferences to either the partners (or doctors), because of embarrassment. Disparity between the reality of sex with their partner and their preferred sexual fantasy (whether or not unconventional) used during masturbation is another cause of DE (47). That disparity takes many forms, such as partner attractiveness, body type, sexual orientation, and the specific sex activity performed (10,48).

Clinical experience affirms that bifurcating etiology into a rigid duality such as psychogenic and biologic is too categorical. Genetic predispositions affect the typical speed and ease of ejaculation for any particular organism; however, many of these components are then influenced by experience and present context (49). Biogenic and psychogenic etiologies are neither independent nor mutually exclusive. The STP and other biopsychosocial-cultural models all explain this variation both between and within given individuals, and provide a better theoretical basis for understanding DE (5,10).

Evaluation and diagnosis

The evaluation of DE focuses on uncovering causes of the disorder. A urologist will often conduct a genitourinary examination and medical history that may identify physical anomalies, as well as contributory neurologic and endocrinologic (especially androgen levels) factors (50). Attention should be given to identifying reversible urethral, prostatic, epididymal, and testicular infections for secondary DE in particular, adverse pharmaceutical side effects—most commonly from SRI’s, or 5-αRI—should be ruled out. Evaluate for illnesses that result in neuropathies, e.g., diabetes, multiple sclerosis. Finally, all clinicians should be mindful about surgical sequelae; prostate cancer (PCa) treatments in particular are notorious for creating a host of problematic orgasmic patterns, which may not meet diagnostic manual standards, yet deserve compassionate guidance for the patient/partner (8,51,52).

While objective diagnostic procedures have scientific and research appeal, in clinical settings the diagnosis of DE is often subjective and imprecise. There are no syndrome-specific tests or inventories to support a more objective diagnosis, and the most valuable diagnostic tool is a focused sex history (sex status) (3,53). For instance, some men with an IELT of 20–25 minutes may be deliberately delaying their ejaculation, while others might choose to stop intercourse in frustration when not ejaculating after 10 minutes of coitus, if they “knew” they would not eventually ejaculate. That was especially true if they believed their partner was “already done”. The HCC’s history taking must parse why coitus was voluntarily discontinued. Just as pathophysiology should not be assumed without medical investigation, a psychogenic etiology should not be assumed and a sex status is critical (53). A sex status typically begins by differentiating DE from other sexual problems and reviewing the conditions under which the man can ejaculate. Perceived partner attractiveness, the use of fantasy during sex, anxiety-surrounding coitus and masturbatory patterns all require meticulous exploration. Identify important causes of DE by juxtaposing an awareness of his cognitions and the sexual stimulation he experiences during masturbation versus a partnered experience.

Below are questions, clinicians can incorporate into the interview to enhance understanding: “What is the frequency of your masturbation?” “How do you masturbate?” “In what way does the physical stimulation you provide yourself differ from your partner’s stimulation style, in terms of speed, pressure, etc.?” “During masturbation do you find that you change bodily movements or technique, if you feel ejaculation approaching and want it to happen?” “What are the differences you experience during self-stimulation versus partner-stimulation?” “Help me understand, in what specific way partner stimulation may be insufficient?” “Have you communicated your preference to your partner and if so, what was their response?” At some point the patient might balk at these personal and intrusive questions, but once the patient is assured that research has shown such information is critical to successful outcome, refusal to engage in such inquiry is rare.

Assess for the degree of immersion and focus on “arousing” thoughts and sensations during masturbation versus partnered sexual activity including: fantasy, watching/reading pornography, sexy versus anti-erotic intrusive thoughts, e.g., “It’s taking too long!” How do his thoughts/feelings during sex with a partner differ from those during solo masturbation? Additional questions will identify other etiological factors that improve or worsen performance, (particularly those related to psychosexual arousal). Obtain the disorder’s development history and if orgasm was possible previously. Review life events/circumstances temporally related to orgasmic cessation. Investigate previous treatment approaches, including the use of herbal therapies, home remedies, etc., and if any benefit was obtained. Information regarding the partners’ perception of the problem and their satisfaction with the relationship may assist treatment planning (54). Sexual and relationship inventories in general and even ones specific to ejaculation, like the MSHQ (55) may improve research methodology, but regrettably provide limited clinical utility.

Psychosexual therapy of DE based on the STP model

A safe effective medication for DE does not yet exist. When and if such a drug becomes available, this author’s transdisciplinary perspective supports the appropriate use of that medication when combined with counseling (6). However, there are still numerous techniques, which can be combined to treat DE including and not limited to sex education, cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness, psychodynamic exploration of underlying conflicts, and/or couples therapy (56,57). Patient and partner (when present) education should be integrated into the history taking process to the extent it does not interfere with rapport building or obtaining the necessary information. Be sensitive to patient preference regarding partner participation, as patient and partner cooperation is more critical to successful treatment than partner attendance at all office visits (53). Before the evaluation concludes, offer the patient a formulation that highlights the immediate cause of his problem and how it can be alleviated. Explain how the mental and physical erotic stimulation he is receiving is insufficient for him to ejaculate in the manner he desires (manual, oral, coital, etc.). Usually the patient will ask about prognosis. Provide a hopeful answer based on clinical evidence, such as: “presuming you are able to accept the guidance provided, many patients find improvement within a range of a few weeks to a few months’ timeframe.” Success depends on the patient’s willingness to follow therapeutic recommendations, which will be influenced by the extent of organicity, relational issues, and the depth and degree of deeper patient/partner psychodynamic problems.

Help the man identify behaviors that enhance his ability to be immersed in excitation and minimize inhibiting thoughts, in order to reach ejaculation in his preferred manner. Discussion of a potential biologic predisposition is useful in reducing patient and partner anxiety and mutual recriminations, while improving therapeutic alliance (8). Current treatments usually emphasizes integrating behavioral masturbatory retraining, within a nuanced sex therapy (2,37,45,53,58,59). Masturbation can serve as rehearsal for partnered sex. By informing the patient how masturbation conditioned his response, stigma is minimized and partner cooperation can be evoked. Of course, masturbation retraining is only a means to an end; the goal of DE therapy is evoking higher levels of psychosexual arousal within mutually satisfying experiences.

Men with primary DE need to identify their sexual arousal preferences through self-exploration and stimulation. Masturbation training is similar to models described for women; yet the use of vibrators, often recommended by urologists, are rarely needed (58). Progressing from neutral to pleasurable sensations is encouraged (initially without ejaculation) to remove “demand” aspects of performance (45). Fantasizing and use of erotica (including internet pornography) can help block thoughts that might otherwise interfere with arousal. Some men with DE display an over-eagerness to “please” partners, at the expense of their own pleasure. Validate (not encourage) an auto-sexual orientation when encountering it in a man, and assist in removing stigma suggesting withholding toward his partner. Finally, encourage the man and his partner to share their preferences, so that both their needs are met.

For both primary and secondary DE (as soon as therapeutically possible) obtain an agreement from the patient to temporarily refrain from ejaculating alone. If he won’t stop, negotiate a reduction in his masturbatory ejaculatory frequency with a minimum commitment of no orgasm within 72 hours (arbitrary but based on experience) of his next partnered experience. If he initially insists on continuing to masturbate alone, it is essential he do so in a manner different from his normal routine. Have him limit his orgasmic outlet from his easiest current capacity (usually a specific masturbation style), and progressively “shaping” it (with repeated attempts) closer to what he will experience with partnered sex. This can vary from changing hands or the position he uses during self-stimulation, to masturbating in his partner’s presence. Transitioning from manual to oral, to coital stimulation is typical, as each provides progressively less friction than the other.

Twenty-five years ago, lack of adequate stimulation was the salient variable for an early primary DE case of this author. A young and sexually naïve Orthodox Jewish couple presented with a symptom of primary DE, which interfered with their desire for a large family. The cause was sexual ignorance, inexperience, and a complete lack of adequate penile stimulation. They lay quietly together during coitus, waiting for his ejaculation to occur. Once informed of the benefit of “thrusting”, a pregnancy soon ensued and follow-up found them with eight children (60). But regrettably, such sex education is almost never sufficient in and of itself.

Primary and secondary DE treatments share similarities. First, counsel the “secondary” patients to suspend masturbatory activity and temporarily only ejaculate from their desired goal activity, e.g., coital orgasm. Reducing or discontinuing masturbation (typically for 14–60 days), often evokes patient resistance. The clinician must provide support to ensure adherence to this suspension. Depending on motivation level, masturbation interruption must sometimes be compromised and negotiated. Encourage a man who continues to masturbate to alter style (“switch hands”) and to approximate the stimulation likely to be experienced through manual, oral, or vaginal stimulation by his partner (10). The patient’s coital bodily movements and fantasies should approximate the thoughts and sensations experienced in masturbation. Single men should use condoms during masturbation to rehearse “safe sex”.

When appropriate, the clinician might incorporate this conversation into treatment: “Regrettably, your masturbation has conditioned you to be an expert masturbator who only fully responds to very specific stimuli.” “With all your practice, no wonder there’s a problem… anyone would (humor helps here)!” “Do you know what will help solve your problem?” The answer: “You need to temporarily stop masturbating. Do not have an orgasm unless it’s by partner stimulation.” Depending on patient’s response: “If you continue masturbating, do so only if your partner is present.” Then ask: “Can you do that? Are you willing?” “Any ideas on how to do it?” If he doesn’t, then suggestions must be offered. Success will require most men to be taught to: “maneuver your body with your partner’s, so your sensations and erotic thoughts become as stimulating, or more so than when you masturbate.” Telling a man to postpone masturbating until he is able to have a partnered orgasm, (especially a coital one), is likely to evoke a predictable “why”, at best, and “no I won’t” at worst. Encouraging compliance necessitates understanding that this is a temporary requirement needed to expand sexual repertoire.

Temporary cessation of masturbation (and/or alteration of both masturbation style and frequency) required by most men is difficult to accomplish. Below are tips to manage resistance and facilitate success. Coach an answer if the patient appears to draw a blank stare when asked how he might think and move his body differently. How to coach? First ask more questions: “What would help you get more lost in the moment?” Familiar sports analogies about “being in the zone” may help.

Sex therapists may find that simultaneous exploration of both intra and interpersonal conflicts, depending on progress is required. Support men who are passive and only concerned with their partner’s pleasure to be more aggressive. Give men permission to move in a manner to maximize their pleasure. Help the patient become more “selfish” and not worry as much about his partner. Their partner will take care of themselves, or he can learn how to help later. Reframe the concept of selfishness: “Selfish is not allowing your partner the pleasure of gratifying you.” This is usually at odds with his need to provide stimulation that is best for the partner at the expense of himself. Ironically, there are men suffering from DE who naively interrupt stimulation that is close to bringing them to orgasm because they feel their partner is “not ready”. They subsequently find themselves unable to ejaculate later, once their partner’s excitement declines post-orgasmically.

Sexual fantasies may need realignment so that thoughts experienced during masturbation better match those occurring during coitus. Efforts to increase the arousing capacity of the partner, by reducing the disparity between the man’s fantasy and the actuality of sex with his partner may help. Significant disparity tends to characterize more severe relationship problems and treatment recalcitrance (47).

Reassurance is required for men and their partners who suffer from DE secondary to aging. As men age there is an expected lengthening of ejaculatory latency, lengthening of their refractory period and inconsistency of orgasmic attainment. Accepting this knowledge is critical to helping them avoid the anti-sexual thoughts, which will inhibit ejaculation from taking place if more is expected from an aging body than reasonable.

Outcome

Success rates for treatment are greater than 75%. Approximately 20% of these men will experience an intravaginal ejaculation in less than 6 weeks of employing these techniques (2). Others will only be able to intermittently ejaculate with their partner. Obviously, not all cases resolve themselves easily. Often coital orgasms are obtained, but no longer remain the preferred choice. Despite being the patient/partner’s initial preference, coital orgasms may be less pleasurable and intense than masturbatory orgasms. Nonetheless, for many men and their partners it is often subjectively the most satisfying for a variety of psychosocial-cultural reasons. This potential conundrum is best resolved when the HCC allows the choice of post treatment orgasmic preference to remain the decision of the man/couple. Sometimes these men will need clinician support to express their preference for non-coital orgasms, especially when their coital orgasms were less satisfactory and only obtained by painstaking effort. However, clinicians who readily negotiate compromise with a couple whose female partner prefers non-coital stimulation should recognize the parallel with men suffering from coital DE. Finally, for some men with DE, failure is predetermined secondary to partner psychopathology, values regarding pornography and their relationship issues, etc.

Partner issues affect males’ ejaculatory interest and capacity, but two require special attention: fertility and resentment. The pressure of a woman’s “biological clock” is often an initial treatment driver. The women—and often the man—usually resist anything delaying their plan to conceive. If the HCC suspects the patient’s DE is related to fear of conception, inquire if there is a disparity experienced during sex when using contraception versus “unprotected” sex. Such a “test” is a powerful diagnostic indicator. If the DE only occurs during “unprotected” sex, the HCC can assume that impregnation reluctance is a primary variable. Resolution typically requires individual work with the man and occasionally with the partner.

Fertility related or not, patient/partner anger is an important causational factor, and must be ameliorated through individual and/or conjoint consultation. Anger acts as a powerful anti-aphrodisiac. While some men avoid sexual contact entirely when angry, others attempt to perform, only to find themselves modestly aroused and unable to function. The man’s assertiveness should be encouraged, but the HCC should also remain sensitive and responsive to the impact of change on the partner, as well as alterations in the couple’s equilibrium.

As treatment progresses, interventions may be experienced as mechanistic and insensitive to the partner’s needs and goals. Understandably, partners’ respond negatively to the impression the patient is essentially masturbating himself with her body, as opposed to engaging in a connected lovemaking. This perception is exacerbated when men need pornography to distract themselves from negative thoughts in order to function. Indeed, some men are disconnected emotionally from their partners. The HCC must empathically help the partner become comfortable with the idea of temporarily postponing desired intimacy. Once the patient is functional, the clinician can encourage a man/couple towards greater intimacy. Alternatively, both partners may be disconnected from each other, but otherwise in a valued stable relationship. Support the patient’s goals, but do not push the man (couple) towards the clinician’s own preordained concept of a relationship. Instead, embrace McCarthy’s “good enough” sex model (61).

The treatment approach recommended above is not merely for heterosexual men. This author recently provided a successful 4-month treatment with a homosexual man (referred by his psychiatrist) who never had been able to orgasm with a partner. Etiology was primarily two-fold: first, his orgasmic capacity was impeded by the SSRI he was using successfully for his life-long obsessive-compulsive disorder. Second, he was conditioned to a fantasy of “men who smoked”. Feeling ashamed, he never discussed this with his partners or previous doctors. Initially, he reported masturbating daily each morning via Skype (in a global pornography video chat room) with multiple European and Asian men who smoked. By temporarily suspending masturbation, he was able to ejaculate with a new partner within 4 weeks of beginning treatment. While that relationship eventually ended, the patient found he was still able to ejaculate with other sex partners by not masturbating to orgasm for at least 72 hours in advance of any new date.

The more relationship strife, the less likely treatment will succeed. Identifying psychological factors does not mean they must all be addressed by the initial HCC. Clinicians should practice to their level of comfort, but should not hesitate to refer as needed (53,62,63). For instance, given the real limitations of penile rehabilitation therapies, men often need help accepting their sex life has changed (64). Sexual efficacy, confidence and satisfaction need to be defined in broader terms. Helping the man identify and request the sexual stimulation he enjoys most becomes critical. Here vibratory devices may become desirable, as greater stimulation is required secondary to the damage caused by the PCa treatments (65,66). Sex therapists may find themselves humbled when rehabilitating a response that is anatomically limited. One man treated for post-prostatectomy orgasmic change indicated: “it used to feel like a jet engine…it became a paperclip after surgery. You’ve got me back to a prop plane and that is what I need to live with.” Certainly, the greater the nerve damage, the more psychotherapy facilitates adjustment to loss, rather than restoration of function.

The good success rates reported by sex therapists when treating DE (10,37,67) should only be viewed as exploratory. Althof notes the difficulty in evaluating sex therapy treatment outcomes, because the published studies use small samples, uncontrolled, non-randomized methodologies, and lack validated outcome measures (39). Disparity between the results of different professionals may well also reflect different treatment populations. Only well designed multicenter clinical trials will establish an answer.

Conclusions

DE is an academic stepchild when compared to the vast number of PE studies in the sexual medicine literature. A major source of that disparity is related to no regulatory agency anywhere in the world having yet approved a drug for DE. There is no question that a drug treatment for men with severe DE would be beneficial (regardless of the degree of psychosocial-behavioral and cultural factor complications) although patients would benefit even more from medical treatment augmented by counseling. This is consistent with the recommendations many have provided to the sexual medicine community that an approach be developed for DE similar to integrated treatments for ED and PE (8,29,49,68-70).

As a clinician and researcher this author’s primary concern is making care accessible to those who desire treatment using ejaculatory definitions that are valid, and consistent globally across centers of excellence. This goal (access, validity, reliability) is fulfilled using a DE definition which differs from the ISSM and DSM-5 guidelines but still incorporates the critical tenets of time, control, and distress (19-22,28). This approach emphasizes the utility of a biopsychosocial-cultural perspective combined with particular attention to the patient’s narrative. Treatment is always conducted in the context of a patient-centered holistic approach that integrates a variety of therapies as needed whether for DE or any other sexual concern.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the administrative help of Alessia DiGenova.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author served as an Advisor to the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 Task Force & Work Group. The author is a long time member of the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM), (formerly the ISSIR) and has served on the Standards Committee (2007–2013), the Standards Ad Hoc PE Definition Subcommittee (2007–2010), and the Communications Committee (2007–Present). The author was a member of the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th ICSM Consultations, serving on the Male Ejaculation Committee for the 2nd and 4th Consultations.

(A): The STP is a registered trademark owned by the MAP Educational Fund, a 501(c)(3) public charity. Figure 1 and other STP images are all available free for the reader’s use from mapedfund.org.

References

- Perelman MA, McMahon C, Barada J. Evaluation and treatment of the ejaculatory disorders. In: Lue T. editor. Atlas of Male Sexual Dysfunction. Philadelphia: Current Medicine, 2004:127-57.

- Perelman MA, Watter DN. Delayed Ejaculation. In: Levine SB, Risen CB, Althof SE. editors. Handbook of Clinical Sexuality for Mental Health Professionals. 3rd Edition. New York and London: Routledge, 2016.

- Althof SE, Rosen RC, Perelman MA, et al. Standard operating procedures for taking a sexual history. J Sex Med 2013;10:26-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. Idiosyncratic Masturbation Patterns: A Key Unexplored Variable in the Treatment of Retarded Ejaculation by the Practicing Urologist. J Urol 2005;173:340. Abstract 1254. [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. The sexual tipping point: a mind/body model for sexual medicine. J Sex Med 2009;6:629-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. Advocating For a Transdisciplinary Perspective in Sexual Medicine. Curr Sex Health Rep 2015;7:1-2. [Crossref]

- Perelman MA. Why the Sexual Tipping Point® Model? Curr Sex Health Rep 2016;8:39-46. [Crossref]

- Perelman MA. Delayed Ejaculation. In: Binik YM, Hall KS. editors. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. 5th edition. New York: Guilford Press, 2014.

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281:537-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA, Rowland DL. Retarded ejaculation. World J Urol 2006;24:645-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowland DL. Neurobiology of sexual response in men and women. CNS Spectr 2006;11:6-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parelman MA. Regarding ejaculation, delayed and otherwise. J Androl 2003;24:496. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Hamid IA. Saleh el-S. Primary lifelong delayed ejaculation: characteristics and response to bupropion. J Sex Med 2011;8:1772-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowland D, van Diest S, Incrocci L, et al. Psychosexual factors that differentiate men with inhibited ejaculation from men with no dysfunction or another sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2005;2:383-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. Patient highlights. Delayed ejaculation. J Sex Med 2013;10:1189-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corona G, Mannucci E, Petrone L, et al. Psychobiological correlates of delayed ejaculation in male patients with sexual dysfunctions. J Androl 2006;27:453-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. Retarded ejaculation. Curr Sex Health Rep 2004;1:95-101. [Crossref]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. Available online: http://psy-gradaran.narod.ru/lib/clinical/DSM5.pdf

- McMahon CG, Althof S, Waldinger MD, et al. An evidence-based definition of lifelong premature ejaculation: report of the International Society for Sexual Medicine Ad Hoc Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation. BJU Int 2008;102:338-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMahon CG, Althof SE, Waldinger MD, et al. An evidence-based definition of lifelong premature ejaculation: report of the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) ad hoc committee for the definition of premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 2008;5:1590-606. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Althof SE, McMahon CG. Contemporary Management of Disorders of Male Orgasm and Ejaculation. Urology 2016;93:9-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serefoglu EC, McMahon CG, Waldinger MD, et al. An evidence-based unified definition of lifelong and acquired premature ejaculation: report of the second international society for sexual medicine ad hoc committee for the definition of premature ejaculation. Sex Med 2014;2:41-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD, Quinn P, Dilleen M, et al. A multinational population survey of intravaginal ejaculation latency time. J Sex Med 2005;2:492-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD, McIntosh J, Schweitzer DH. A five-nation survey to assess the distribution of the intravaginal ejaculatory latency time among the general male population. J Sex Med 2009;6:2888-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patrick DL, Althof SE, Pryor JL, et al. Premature ejaculation: an observational study of men and their partners. J Sex Med 2005;2:358-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McMahon CG, Rowland D, Abdo C, et al. Disorders of Orgasm and Ejacuation in Men. Available online: http://www.issm.info/images/book/Committee%2017/

- Waldinger MD, Hengeveld MW, Zwinderman AH, et al. An empirical operationalization study of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for premature ejaculation. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 1998;2:287-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serefoglu EC, McMahon CG, Waldinger MD, et al. An evidence-based unified definition of lifelong and acquired premature ejaculation: report of the second International Society for Sexual Medicine Ad Hoc Committee for the Definition of Premature Ejaculation. J Sex Med 2014;11:1423-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Althof SE, McMahon CG, Waldinger MD, et al. An Update of the International Society of Sexual Medicine's Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Premature Ejaculation (PE). J Sex Med 2014;11:1392-422. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosen RC, McMahon CG, Niederberger C, et al. Correlates to the clinical diagnosis of premature ejaculation: results from a large observational study of men and their partners. J Urol 2007;177:1059-64; discussion 1064. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowland DL, Kolba TN. Understanding the effects of establishing various cutoff criteria in the definition of men with premature ejaculation. J Sex Med 2015;12:1175-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowland DL, Neal CJ. Understanding men's attributions of why they ejaculate before desired: an internet study. J Sex Med 2014;11:2554-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patrick DL, Rowland D, Rothman M. Interrelationships among measures of premature ejaculation: the central role of perceived control. J Sex Med 2007;4:780-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jern P, Gunst A, Sandqvist F, et al. Using Ecological Momentary Assessment to investigate associations between ejaculatory latency and control in partnered and non-partnered sexual activities. J Sex Res 2011;48:316-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waldinger MD. Toward evidence-based genetic research on lifelong premature ejaculation: a critical evaluation of methodology. Korean J Urol 2011;52:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olivier B, Chan JS, Snoeren EM, et al. Differences in sexual behaviour in male and female rodents: role of serotonin. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2011;8:15-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masters WH, Johnson VE. editors. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little, Brown & Co, 1970.

- Perelman MA. The history of sexual medicine. In: Tolman DL, Diamond LM, editors. APA Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology, Vol 2: Contextual Approaches. Washington: American Psychological Association, 2014:137-79.

- Althof SE. Psychological interventions for delayed ejaculation/orgasm. Int J Impot Res 2012;24:131-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laurent SM, Simons AD. Sexual dysfunction in depression and anxiety: conceptualizing sexual dysfunction as part of an internalizing dimension. Clin Psychol Rev 2009;29:573-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zemishlany Z, Weizman A. The Impact of Mental Illness on Sexual Dysfunction. In: Balon R. editor. Sexual Dysfunction: the Brain-Body Connection. Basel: Karger, 2008:89-106.

- Atlantis E, Sullivan T. Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med 2012;9:1497-507. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johannes CB, Clayton AH, Odom DM, et al. Distressing sexual problems in United States women revisited: prevalence after accounting for depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:1698-706. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Apfelbaum B. Retarded ejaculation: a much-misunderstood syndrome. In: Lieblum SR, Rosen RC. editors. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press, 1989:168-202.

- Apfelbaum B. Retarded ejaculation: a much-misunderstood syndrome. In: Leiblum SR, Rosen RC. editors. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press, 2000:205-41.

- Perelman MA. FSD partner issues: expanding sex therapy with sildenafil. J Sex Marital Ther 2002;28 Suppl 1:195-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. Integrating sildenafil and sex therapy: unconsummated marriage secondary to ED and RE. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy 2001;26:13-21.

- Rowland DL, Keeney C, Slob AK. Sexual response in men with inhibited or retarded ejaculation. Int J Impot Res 2004;16:270-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. A new combination treatment for premature ejaculation: a sex therapist's perspective. J Sex Med 2006;3:1004-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corona G, Jannini EA, Lotti F, et al. Premature and delayed ejaculation: two ends of a single continuum influenced by hormonal milieu. Int J Androl 2011;34:41-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. Post-Prostatectomy Orgasmic Response. J Sex Med 2008;5:248-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- International Socity for Sexual Medicine. Understanding and treating retarded ejaculation: a sex therapist’s perspective. Available online: http://www.issm.info/news/review-reports/understanding-and-treating-retarded-ejaculation/

- Perelman MA. Sex coaching for physicians: combination treatment for patient and partner. Int J Impot Res 2003;15 Suppl 5:S67-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, et al. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 2000;56:899-905. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosen RC, Catania J, Pollack L, et al. Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ): scale development and psychometric validation. Urology 2004;64:777-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davidson RJ, Kaszniak AW. Conceptual and methodological issues in research on mindfulness and meditation. Am Psychol 2015;70:581-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. Delayed Ejaculation. In: Binik YM, Hall KS. editors. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford, 1980.

- Nelson CJ, Ahmed A, Valenzuela R, et al. Assessment of Penile Vibratory Stimulation as a Management Strategy in Men with Secondary Retarded Orgasm. Urology 2007;69:552-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sank LI. Traumatic masturbatory syndrome. J Sex Marital Ther 1998;24:37-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. The urologist and cognitive behavioral sex therapy. Contemporary Urology 1994;6:27-33.

- Metz ME, McCarthy BW. The “Good-Enough Sex” model for couple sexual satisfaction. Sex Relation Ther 2007;22:351-62. [Crossref]

- Perelman MA. Combination therapy for sexual dysfunction: integrating sex therapy and pharmacotherapy. In: Balon R, Segraves RT. editors. Handbook of Sexual Dysfunction. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, 2005:13-41.

- Perelman MA. Psychosocial evaluation and combination treatment of men with erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am 2005;32:431-45. vi. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burnett AL. Current rehabilitation strategy: clinical evidence for erection recovery after radical prostatectomy. Transl Androl Urol 2013;2:24-31. [PubMed]

- Nelson CJ, Ahmed A, Valenzuela R, et al. Assessment of penile vibratory stimulation as a management strategy in men with secondary retarded orgasm. Urology 2007;69:552-5; discussion 555-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tajkarimi K, Burnett AL. The role of genital nerve afferents in the physiology of the sexual response and pelvic floor function. J Sex Med 2011;8:1299-312. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA, Watter DN. Delayed Ejaculation. In: Kirana PS, Tripodi F, Reisman Y, et al. editors. The EFS and ESSM Syllabus of Clinical Sexology. Amsterdam: Medix Publishers, 2013:678-94.

- Althof SE, McMahon CG, Waldinger MD, et al. An update of the International Society of Sexual Medicine's guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of premature ejaculation (PE). J Sex Med 2014;11:1392-422. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. Integrated sex therapy: a psychosocial-cultural perspective integrating behavioral, cognitive, and medical approaches. In: Carson CC, Kirby RS, Goldstein I, et al. editors. Textbook of Erectile Dysfunction. 2nd ed. London: Informa Healthcare, 2009:298-305.

- Perelman MA. Epiologue: Cautiously Optimistic For the Future of A Transdisciplinary Sexual Medicine. In: Lipshultz LI, Pastuszak AW, Giraldi A, et al. editors. Management of Sexual Dysfunction in Men and Woman: An Interdisciplinary Approach. New York: Springer, 2016.