Wide-based oblique anastomosis reduces urethral stricture rate following the transverse preputial island flap procedure

Highlight box

Key findings

• The overall postoperative complication rate in our study was 20.8%, especially no urethral stricture (US) occurred.

What is known and what is new?

• The core of wide-based oblique anastomosis (WOA) technique is to perform a breadthwise anchoring of the dorsal side of the anastomosis to corpus cavernosum.

• The postoperative wide dorsal anastomotic morphology confirms the advantage of the WOA technique.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• WOA technique is straightforward and effective, especially in the prevention of postoperative US.

• WOA technique can be well integrated with transverse preputial island flap procedure.

Introduction

The transverse preputial island flap (TPIF) procedure, reported by Duckett in 1980, remains one of the classic single-stage procedures for severe hypospadias repairs. Although the TPIF procedure has since been improved, a recent meta-analysis showed that the incidence of postoperative complications remained as high as 42% over the last decade. Among them, urethral stricture (US) is a refractory complication, with an incidence of 13% (1). US usually occurs at the anastomosis site between the TPIF and the proximal urethral opening (2,3). Thus, the urethral anastomosis technique may need to be improved. In this study, we developed wide-based oblique anastomosis (WOA) technique during the TPIF procedure, and analyzed its effect on postoperative complications, especially US. We present this article in accordance with the SUPER reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-133/rc).

Methods

Data were collected retrospectively from consecutive patients who underwent the TPIF procedure for primary hypospadias repair by the same pediatric urologist at Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine between January 2018 and June 2023. Collected information included age at surgery, operative details, and outcomes at follow-up. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (No. 2021-IRB-322) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) severe ventral curvature (>30°) after degloving; (II) a primary single-stage TPIF procedure with or without the Duplay procedure; (III) surgical details were recorded completely; and (IV) follow-up over 1 year.

Surgical procedure and antibiotics management

The surgical procedures for TPIF have been described previously (4). The major steps are described in Figure 1. The urethral plate and the corpus spongiosum were transected after degloving. The proximal urethral plate and the corpus spongiosum were dissociated from the corpus cavernosum, and then tension-free refixed to the corpus cavernosum with interrupted sutures. The remnant ventral curvature was corrected by dorsal plication (<30°) or ventral corporoplasty (≥30°) with Buck fascia or urethral plate flap (5). A 1.2–1.5 cm wide prepuce flap was harvested, transposed ventrally, and tubularized over 8–12 Fr catheters, leaving a 10-mm-long flap at the proximal end for further anastomosis. The glans channel was incised adequately to a diameter corresponding to 10–14 Fr. The tubularized prepuce flap was transposed through the glans channel. The dorsal sutured midline of tubularized prepuce flap anchored longitudinally toward the ventral surface of corpus cavernosum with interrupted sutures. Glansplasty was subsequently performed. Then the WOA technique was performed: the dorsal edge of the proximal end of the flap was sutured to the dorsal edge of spatulated native urethra, simultaneously breadthwise anchoring to the corpus cavernosum with 4–5 stitches, and the ventral edge of the proximal end of the flap was then sutured continuously with the ventral edge of spatulated native urethra (Figures 1F,1G,2A). The difference between the WOA and the classic oblique anastomosis is shown in Figure 2. The neourethra and urethral anastomotic site were covered by the flap pedicle (if insufficient, combined with the pedicled tunica vaginalis). The foreskin was trimmed and shaped. The catheters were removed 3–4 weeks postoperatively.

There were some variations in the surgical procedures. If the urethral defect was longer than the available tubularized prepuce flap, a Duplay procedure was performed for proximal urethroplasty. In the case of an insufficient prepuce flap despite the combined application of the Duplay procedure, the patient subsequently underwent staged TPIF and was not included in the cohort.

Antibiotics were administered to prevent infection during the perioperative period and for approximately 7 days postoperative. If signs of infection, such as skin redness and swelling, were observed, the duration of antibiotic treatment was extended accordingly.

Postoperative follow-up and assessment

Routine follow-up for all patients included clinical assessment at 6 weeks and 6 months postoperatively, and every 2–3 years thereafter. Online follow-up was also conducted at least once a year by telephone, video call, and WeChat. If any complications were suspected through online follow-up, further clinical assessment was conducted. Postoperative complications included fistula, urethral diverticulum, US, meatal stenosis, dehiscence, and ventral curvature. US was diagnosed by (I) obstructive voiding symptoms; (II) Qmax <2 standard deviations in uroflowmetry; and (III) further calibration <8 Fr in infants, <10 Fr in prepubescent individuals, or <12 Fr in postpubescent individuals. Urethral dilation was not routinely performed at follow-up. During reoperation for any complications, urethral calibration was routinely performed to further identify the presence of US.

Statistical analyses

Normality was analyzed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Univariate analysis of potential risk factors for postoperative complications was analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test or χ2-test. The level of statistical significance was prospectively determined to be P<0.05. All analyses were carried out using SPSS software, version 26.

Results

A total of 72 patients were included in the study. The median age at surgery was 1.6 years (range, 0.5–13.7 years). According to Orkiszewski’s classification of hypospadias (6), the location of the corpus spongiosum division was penile in 27 patients (37.5%) and proximal in 45 patients (62.5%). The median glans width was 13 mm (range, 6–30 mm). The median ventral curvature after degloving was 45° (range, 30–150°). A total of 56 patients (77.8%) underwent the TPIF procedure for hypospadias repair, while 16 patients (22.2%) underwent TPIF + Duplay procedures. The median neourethra length was 32 mm (range, 20–60 mm). At a median follow-up period of 4.1 years (range, 1.1–6.6 years), complications occurred in 15 patients (20.8%), including nine cases of fistula, seven cases of urethral diverticulum and two cases of meatal stenosis. Some patients presented with two complications. No cases of US, urethral dehiscence, or ventral curvature occurred. Complications occurred at a median time of 1 month (range, 0.5–6 months) after operation. According to the classification of hypospadias, complications incidence was 14.8% in the penile type and 24.4% in the proximal type. Univariate analysis showed no statistical association between postoperative complications and potential risk factors included in the model (Table 1).

Table 1

| Agents | No complication (n=57) | Complication (n=15) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.7 [1.0, 2.8] | 1.3 [0.8, 2.3] | 0.18 |

| Location of corpus spongiosum division | 0.38 | ||

| Penile | 23 (85.2) | 4 (14.8) | |

| Proximal | 34 (75.6) | 11 (24.4) | |

| Glans width (mm) | 13.0 [11.5, 14.8] | 12.0 [11.0, 14.0] | 0.17 |

| Ventral curvature after degloving (°) | 45 [45, 70] | 60 [45, 90] | 0.12 |

| Urethroplasty technique | 0.73 | ||

| TPIF | 45 (80.4) | 11 (19.6) | |

| TPIF + Duplay | 12 (75.0) | 4 (25.0) | |

| Neourethra length (mm) | 30 [28, 40] | 40 [26, 44] | 0.38 |

Estimates were given as median [quartile 1, quartile 3] or frequency (percentage). TPIF, transverse preputial island flap.

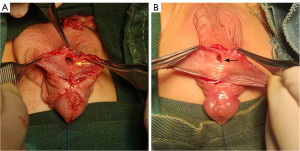

The postoperative anastomotic morphology was observed during subsequent reoperations for diverticulum repair. Two of the seven cases of urethral diverticulum were secondary to meatal stenosis, while other five cases were unrelated to US or meatal stenosis (urethral calibration of 10–14 Fr). The dorsal side of the WOA was extensively fixed to the corpus cavernosum, forming a wide-based, spacious lumen (Figure 3A). Comparatively, in our previous case with classic oblique anastomosis (not included in this study), the dorsal side of the anastomosis was fixed at a point to the corpus cavernosum, forming a narrow-based lumen (Figure 3B).

Discussion

The core of WOA technique is to perform a breadthwise anchoring of the dorsal side of the anastomosis to corpus cavernosum. Our data showed good outcomes of TPIF repair with the application of WOA technique. US did not occur in this study, as compared with 13% in the previous meta-analysis of TPIF repair (1). Besides, the overall complication rate was 20.8% in this study, which was lower than that of 42% in the previous meta-analysis of TPIF repair (1). Duckett (4) first reported the TPIF procedure and described the anastomosis method, including two key points: (I) oblique anastomosis was performed to form a wide anastomotic surface; and (II) then the junction of the flap and proximal urethra was extended distally toward the penis shaft. Several modified TIPF procedures were accompanied by improvements in anastomotic techniques. Aoki et al. (7) made a V-shaped incision at the ventral side of the native urethra before anastomosis. Huang et al. (8) made a V-shaped incision at the dorsal side of the proximal end of flap before anastomosis. Blanc et al. (9) designed an Onlay-Tube-Onlay flap and performed the anastomosis similar to the Onlay procedure. All reported improvements in anastomotic techniques were intended to create a wider anastomotic surface. These reports did not mention breadthwise anchoring of the dorsal side of the anastomosis to corpus cavernosum.

Although a wider anastomotic surface and an extension of dorsal point of anastomosis distally toward penis shaft can reduce the occurrence of anastomotic kinking and stricture, these treatments were not always effective. There were some special situations in the urethral anastomosis. During TPIF procedure, the penis was stretched or erected. After surgery, the penis was usually in a nonerectile state, and the anastomotic distortion and deformation may emerge, followed by surrounding hematoma, exudation, and inflammation. Finally, an irreparable scar may develop at the anastomotic site, resulting in US. Relatively, WOA technique provided an extra breadthwise anchoring to corpus cavernosum, and presented with minimal anastomotic distortion and deformation regardless of penile erection. Thus, the anastomotic scars were milder, benefiting from less hematoma, exudation, and inflammation. In addition, the breadthwise anchoring itself also ensured a wide width of the dorsal side of anastomosis and prevented postoperative narrowing of the lumen. The postoperative wide dorsal anastomotic morphology confirms the advantage of the WOA technique.

Similar breadthwise anchoring has been used in other urethroplasty procedures for failed hypospadias. Wu et al. (10) reported a one-stage repair for US. After scarred urethral tissue excision, the buccal mucosal graft was widely anchored to the corpus cavernosum on the dorsal side of the urethral defect, followed by an Onlay procedure on the ventral side. Xue et al. (11) also reported a one-stage repair for US. After harvesting of pedicled preputial/penile skin flaps, longitudinal edge of flap was sutured to tunica albuginea in corpus cavernosum with a breadthwise distance of 0.5 cm to the other side, followed by flap tubularization. During their follow-up, cystoscopy confirmed a smooth unobstructed neourethra, which benefited from breadthwise anchoring.

US was also related to the poor vascularization of the prepuce flap and the native urethra (12). In our study, priority was given to ensure a well-vascularized pedicle of flap during harvesting, and the native urethra tissue with poor blood supply was trimmed before anastomosis. Staged TPIF procedure for hypospadias repairs have been shown to reduce the risk of postoperative complications (including US) (1). However, it needs to be recognized that staged repairs increased the number of operations, and most likely did not reduce the total number of operations needed for cure. Besides, the risk of multiple reoperations may increase once complications occurred following staged hypospadias repairs (13).

Urethral diverticulum tends to develop secondary to distal urethral obstruction. In our study, the incidence of urethral diverticulum was 9.7%, which is similar to the 10% reported previously (1). Five out of seven cases of diverticulum were unrelated to US or meatal stenosis. This may be attributed to an overly wide flap relative to the outflow tract at the glans. Urethral diverticulum rarely occurs in graft-based repairs, such as the Bracka technique (14,15). Another cause of urethral diverticulum is the lack of spongiosal support around the neourethra (16). In our study, there was a lack of corpus spongiosum at the neourethra site after urethral plate transection. Although the neourethra was covered with the flap pedicle, it still lacked adequate support from the surrounding tissue. Reducing the incidence of urethral diverticulum following the TPIF procedure remains a worthwhile effort.

No risk factors associated with complications were identified in this study. This may be due to the small sample size. However, the present study has other limitations. It was a retrospective single-center study, and all patients were operated on by the same surgeon. Given the inherent variability in patient anatomy, each repair was unique. Postoperative outcomes may be heterogeneous between different institutions or surgeons (1). Multi-center randomized controlled clinical studies with a larger sample size are needed. Although all the emerged complications occurred within 6 months after operation, the actual overall complication rate may be higher if followed beyond adolescence (3,17,18). Further follow-up is required.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that the WOA technique is straightforward and effective, especially in the prevention of postoperative US. The WOA technique can be well integrated with TPIF procedure, and its use is recommended in all cases treated with TPIF procedure.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported financially by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SUPER reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-133/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-133/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-133/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-133/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (No. 2021-IRB-322) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Babu R, Chandrasekharam VVS. Meta-analysis comparing the outcomes of single stage (foreskin pedicled tube) versus two stage (foreskin free graft & foreskin pedicled flap) repair for proximal hypospadias in the last decade. J Pediatr Urol 2021;17:681-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng DC, Yao HJ, Cai ZK, et al. Two-stage urethroplasty is a better choice for proximal hypospadias with severe chordee after urethral plate transection: a single-center experience. Asian J Androl 2015;17:94-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang CX, Zhang WP, Song HC. Complications of proximal hypospadias repair with transverse preputial island flap urethroplasty: a 15-year experience with long-term follow-up. Asian J Androl 2019;21:300-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duckett JW Jr. Transverse preputial island flap technique for repair of severe hypospadias. Urol Clin North Am 1980;7:423-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ru W, Feng C, Tian H, et al. A novel corporoplasty technique with a urethral plate flap in hypospadias repair. Int J Urol 2023;30:666-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Orkiszewski M. A standardized classification of hypospadias. J Pediatr Urol 2012;8:410-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aoki K, Fujimoto K, Yoshida K, et al. One-stage repair of severe hypospadias using modified tubularized transverse preputial island flap with V-incision suture. J Pediatr Urol 2008;4:438-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang Y, Xie H, Lv Y, et al. One-stage repair of proximal hypospadias with severe chordee by in situ tubularization of the transverse preputial island flap. J Pediatr Urol 2017;13:296-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blanc T, Peycelon M, Siddiqui M, et al. Double-face preputial island flap revisited: is it a reliable one-stage repair for severe hypospadias? World J Urol 2021;39:1613-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu M, Chen SZ, Ye WJ, et al. Redo surgery for failed hypospadias treatment using a novel single-stage repair. Asian J Androl 2018;20:311-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xue JD, Xie H, Fu Q, et al. Single-Staged Improved Tubularized Preputial/Penile Skin Flap Urethroplasty for Obliterated Anterior Urethral Stricture: Long-Term Results. Urol Int 2016;96:231-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paraboschi I, Gnech M, Minoli DG, et al. Indocyanine Green (ICG)-Guided Onlay Preputial Island Flap Urethroplasty for the Single-Stage Repair of Hypospadias in Children: A Case Report. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023;20:6246. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ru W, Tang D, Wu D, et al. Identification of risk factors associated with numerous reoperations following primary hypospadias repair. J Pediatr Urol 2021;17:61.e1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu Y, Guan Y, Wang X, et al. Repair of proximal hypospadias with single-stage (Duckett's method) or Bracka two-stage: a retrospective comparative cohort study. Transl Pediatr 2023;12:387-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Wang X, Wu Y, et al. Grafts vs. flaps: a comparative study of Bracka repair and staged transverse preputial island flap urethroplasty for proximal hypospadias with severe ventral curvature. Front Pediatr 2023;11:1214464. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali D, Hanna MK. Symptomatic corpus spongiosum defect in adolescents and young adults who underwent distal hypospadias repair during childhood. J Pediatr Urol 2021;17:814.e1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lucas J, Hightower T, Weiss DA, et al. Time to Complication Detection after Primary Pediatric Hypospadias Repair: A Large, Single Center, Retrospective Cohort Analysis. J Urol 2020;204:338-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rynja SP, de Jong TPVM, Bosch JLHR, et al. Proximal hypospadias treated with a transverse preputial island tube: long-term functional, sexual, and cosmetic outcomes. BJU Int 2018;122:463-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]