Application of decellularized tilapia skin in rabbit urethral reconstruction: an experimental study

Highlight box

Key findings

• We successfully prepared a marine acellular dermal matrix material, decellularized tilapia skin (DTS) and used it in a rabbit urethral defect model for repair. During the urethral defect healing with DTS, the tissue collagen and smooth muscle content were significantly increased and the inflammatory response was milder.

What is known and what is new?

• Urethral reconstruction remains a clinical challenge today. There is no single urethral reconstruction procedure that is accepted by all clinicians, and various postoperative complications are common.

• As a tissue engineering material of marine animal origin with no religious restrictions, DTS is expected to be used in clinical urethral reconstruction due to its effective effect on defect healing and histocompatibility in future.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Tilapia has made the production of tilapia-derived biomaterials economically feasible due to its wide geographic distribution and stable availability. DTS has better biocompatibility as an implant and is expected to be used in the manufacture of various clinical products.

Introduction

In the urethra tissue, urothelial epithelial cells, smooth muscle cells and their associated extracellular matrix (ECM) form a highly ordered elastic luminal structure which are vital for urine and semen transport (1,2). Trauma, inflammation, congenital anomalies and medically induced injuries can cause urethral strictures, urethral fistulas, and other conditions that require surgical reconstruction of the urethra in severe cases. However, there is no single urethral reconstruction procedure that is accepted by all clinicians, and various postoperative complications are common. Urethral reconstruction remains a clinical challenge today (3).

Currently, the gold standard in urethroplasty to treat urethral stricture are autologous grafts from buccal mucosa or genital skin (4,5). Among them, buccal mucosa has greatly improved the success rate of urethral reconstruction over the past two decades due to its excellent physicochemical properties and has become the preferred tissue for urethral reconstruction (1,6). However, patients undergoing replacement urethroplasty using buccal mucosal grafts or tissue flaps may have donor site lesions or insufficient donor material to meet reconstruction needs (7).

Tissue engineering (TE) combines strategies from biology, materials science, medicine, and engineering and provides a therapeutic approach to repair damaged tissues and organs using ECM or synthetic materials (8,9). The ideal material not only has reliable biocompatibility but also provides a biochemical and physical environment similar to that of native tissue, which promotes cell adhesion, proliferation, and production of ECM (10,11). In experimental and clinical urogenital TE, collagen-based materials such as small intestinal submucosa (SIS) and bladder acellularized matrix (BAM) have been successfully used to repair short-segment urogenital defects (4,7,12-14).

Tilapia is a tropical freshwater fish. During the processing of tilapia, a large number of by-products are discarded. These wastes account for 50–70% of the weight of the entire fish (15). The wide geographical distribution and consistent availability of tilapia make large-scale production of tilapia-derived biomaterials economically feasible. Effective utilization of these fish skins can reduce costs while also reducing environmental pollution (16).

Previously, Lv et al. (17) showed that tilapia skin decellularized matrix could promote the healing of large acute wounds in rats by directing cell infiltration, and angiogenesis, regulating the expression and secretion of inflammatory and skin repair-related factors as well. Lau et al. (18) used decellularized tilapia skin (DTS) in a rat cranial defect model to promote bone regeneration. The major component of DTS is collagen which is an important component of connective tissue, accounting for 25–30% of total mammalian protein, and is less immunogenic, making it widely used in TE (19,20) due to circumvent of religious constraints and the risk of zoonosis between mammalian species.

To explore an ideal alternative material for urethroplasty in this study, we decellularized fresh tilapia skins via combinations of physical, chemical and enzyme treatments, and then conducted a randomized controlled trial using DTS for urethroplasty in rabbits urethral defect model with SIS collagen-based scaffold as a positive control, to verify its effect on urethral defect reconstruction. We present this article in accordance with the ARRIVE reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-598/rc).

Methods

Chemical and biological reagents

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), dispase, Pierce universal nuclease, PicoGreen assay kit and type I collagenase were obtained from Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA. SIS was purchased from Cook Biotech, West Lafayette, IN, USA. Anti-α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) was purchased from Novus Biologicals, Englewood, CO, USA. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was purchased from Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA. Secondary antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA. Other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA, unless otherwise stated.

Preparation of DTS

The method for fish skin decellularization used in this study is followed our previous report with some modifications (18). Freshly harvested skins from Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) descaled were cleaned and then immersed into 0.5 mol/L NaOH solution and shaken at 100 rpm for 3 hours and then rinsed with deionized (DI) water until the pH is less than eight. Subsequently, they were then immersed into 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution for 6 hours. Once completion, the fish skins were scraped from the surface with a blade to physically remove the epidermis. After washed with DI water to remove the black residue. Nuclease 25 U/mL in PBS solution was used to remove nucleic acids from the fish skin for 3 hours. After treatment, the fish skins were thoroughly washed with DI water and dried in a freeze-dryer for 24 hours after 3 hours freeze in −80 ℃ freezer. Finally, the decellularized fish skins was cut into 1 cm × 1 cm pieces (Figure 1) after ethylene oxide sterilization.

Characterization of DTS

Residual DNA content measurement

Freeze-dried DTS were cut into 5 mm × 5 mm pieces (n=3). Each piece was weighed and placed into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube. DNA content was quantified using the FavprepTM Tissue Genomic DNA Extraction Mini Kit (Chiyoda Science, Tokyo, Japan) to extract the DNA from the DTS samples and then quantified using the PicoGreen®dsDNA Assay Kit according to the instructions to verify the success of the decellularization process.

Morphology characterization

The morphologies of the DTS and SIS were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). After freeze dry, the samples were fixed to the stages using conductive adhesive. Thereafter the samples were spattered with an ultrathin platinum layer for 90s. Finally, DTS and SIS samples were observed by ultra-high resolution SEM (SU8000, HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan).

Mechanical property characterization

Uniaxial tensile tests were used to determine the mechanical properties of DTS and SIS. Samples were cut into 30 mm × 5 mm strips and mounted on a Universal Testing Systems (Instron 5594, Instron, Norwood, MA, USA). The tensile testing software recorded the dimensions of each specimen. The load sensor was calibrated and the specimens were pulled at a rate of 10 mm/min until failure. The results were recorded by Universal Testing Systems, the maximum tensile stress and Young’s modulus were compiled. The test is repeated at least three times for each set of specimens.

Degradation

DTS samples with a square size of 1 cm × 1 cm were prepared, lyophilized, accurately weighed (Wo), and placed under sterile conditions in 10 mL simulated body fluid (SBF) containing 50 U/mL type I collagenase (18) to simulate in vivo enzymatic degradation. Tubes were capped and incubated at 37 ℃. Every one hour, the solution was removed with a syringe, and the samples were lyophilized and reweighed (Wr). The degradation curve was plotted based on percentage weight loss [(Wo − Wr)/Wo] * 100%.

Animal experiment

Surgical procedure

Experiments were performed under a project license (No. wydw-2022-0463) granted by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee at Wenzhou Medical University, in compliance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guidelines for the care and use of animals.

During the animal experiments, we used 24 New Zealand rabbits. The weight of rabbits were between 2.5–3.0 kg, and rabbits were housed in the animal facilities of Wenzhou Medical University. All surgical procedures were performed under aseptic conditions. Before surgery, DTS and SIS were given a 15-minute rehydrating soak in sterile saline prior to surgery. Sodium pentobarbital (30–50 mg/kg) was administered intravenously via the ear margins to anesthetize rabbits. After an 8 F catheter was inserted, the ventral skin of the penis was incised with a 1.5 cm cut, with each layer being incised in turn and separated down to the urethra (Figure 2A,2B). Group A (n=8) was implanted with a DTS; group B (n=8) was implanted with a SIS; group C (control group, n=8) was not implanted, and the urethral defect was closed directly using 6-0 poly-p-dioxanone suture (PDS) (Figure 2C). After repair, the 6-0 PDS was used to close layer by layer, and 5-0 prolene sutures were left in place to mark the ends of the wound and the catheter was removed (Figure 2D).

Histological, immunohistochemical, and histomorphometric analyses

Overdoses of sodium pentobarbital were administered through rabbit alar vein at 2 and 4 weeks postoperatively. The penises were excised intact for gross examination and histological processing. All tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours and then paraffin embedded. Tissue paraffin blocks were cut into sections with a thickness of 5 µm. The histological analysis was done by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for pathological examination. The angiogenesis in samples were evaluated by numbers of blood vessel formation a blood vessel area measured using ImageJ software as previous reports (21,22). In addition, collagen distribution was evaluated using Masson’s staining. The detection of smooth muscle was accomplished through α-SMA staining in immunohistochemistry (IHC). Tissue inflammatory response detected by TNF-α staining in immunofluorescence (IF).

Statistical analysis

All experimental data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The manual tracking and measurement software used for histomorphometry was NIS-Elements (version 5.11.01). Quantitative analysis of Masson staining, IHC, and IF results was done by ImageJ software (version 1.53t). Experimental data were tested for differences by applying analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-test using SPSS (version 22.0). P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The experimental data were processed using a double-blind method.

Results

In Figure 3, the surfaces and cross sections of DTS and SIS were shown. Compared to fresh tilapia skins, melanin were removed from the DTS surface and the appearance of DTS was similar as that of SIS (Figure 3A,3D). We measured the residual DNA content of DTS. The results showed that DTS retained 38.78±5.84 ng/mg (dry tissue) after the decellularization, a value lower than the 50 ng/mg specified in the industry standard (23). This indicates that the DTS was successful in reducing the DNA content after treatment while maintaining the structural integrity of the fish skin as show in Figure 3. As shown in SEM images of DTS and SIS, DTS successfully preserved its three-dimensional microstructure during processing and appeared to be looser in its internal structure than SIS. In DTS, the collagen fibres showed a clear laminar arrangement, along with the presence of many pores, which render the high permeability properties.

Through measument using a macrometer, it was found that the thickness of DTS and SIS were 0.39±0.04 and 0.22±0.01 mm, respectively. In order to compare the mechanical properties of DTS and SIS, uniaxial tensile tests were performed. From the results, it revealed excellent ductility of DTS with a maximum tensile stress of 20.97±4.46 MPa and Young’s modulus of 130.43±7.00 MPa, while the SIS presented less ductility with a maximum tensile stress of 37.32±3.97 MPa and Young’s modulus of 615.13±7.43 MPa which is in line with its dense structure (Figure 4A). In vitro degradation test, DTS experienced 49% and 86% weight lost after 2 and 4 hours in SBF with 50 U/mL collagenase, respectively. After 6 hours DTS was completely degraded, while 51.26%±5.42% of SIS still remained under the same treatment (Figure 4B) resulted from its dense structure.

All the experimental animals survived throughout the experimental phase. From morphological observation, the penile wounds in group A healed effectively without any significant penile body curvature and the absence of any fistula openings on the surface (Figure 5A). On the other hand, group B experienced a little curvature of the penis with a slight contracture visible in the wound, although the wound healed well overall (Figure 5B). Conversely, group C suffered from an inadequately healed penile wound featuring severe scarring, substantial contracture, and a ventral fistula opening that adversely impacted erectile function (Figure 5C).

H&E staining at week 2 and week 4 in Figure 6 revealed an intact, stratified uroepithelium on the surface of the excised ventral urethra, with organized smooth muscle and blood vessels visible beneath the uroepithelium. At 2 weeks postoperatively, neither the DTS nor the SIS patch had completely disintegrated in the rabbit penis. In group A, the DTS in the penis showed flaky disintegration and resulted in local deposition of collagen fibers with fibroblast infiltration, but no significant inflammatory cells were detected around DTS fragments (Figure 6A). In group B, it showed significant delamination of the SIS patch under high magnification, with heavy infiltration of inflammatory cells around the SIS laminars (Figure 6B). Group C showed typical loose connective tissue with reticular fibrous structures and a few local inflammatory cells under microscopy (Figure 6C). At 4 weeks postoperatively, in both treatments (DTS and SIS implantations), there were no significant rejections were observed as shown in Figure 6D,6E. The collagen fibers between the tissues had deposited significantly to form a lamellar collagen structure, different from the sparse reticular structure in group C (Figure 6F). In group B, a few SIS patches were still visible in the microscopic field, but not completely fused to the tissue (Figure 6E). We examined the neovasculature in defect area in each group at 4 weeks postoperatively (as characterized by endothelialized lumens containing red blood cells) under a high-power field (HPF) microscope (Figure 7). In terms of the number of blood vessels formation, there was significant difference in group A (5.81±2.61/HPF) compared to group C (3.31±2.44/HPF) (Figure 7A) (P=0.006). There was no significant difference between group A and B (P=0.39). Also, there was significant difference in vascular area in group A [(3.20±1.96)×104 pixel/HPF] compared to the group C [(1.47±1.59)×104 pixel/HPF] (Figure 7B) (P=0.04). Similarly, there was no significant difference between group A and B in term of vascular area (P=0.88).

To clarify the severity of inflammation in each group, we detected TNF-α through IF (Figure 8). The results showed that the fluorescence intensity of TNF-α was weak in group A in where DTS was used for defect repair at both 2 and 4 weeks postoperatively (Figure 7C), and on the contrary, the fluorescence intensity of TNF-α in group B in where commercialized SIS was used for urethral defect repair was the strongest among those groups at both 2 and 4 weeks. At 4 weeks postoperatively, the fluorescence intensities increased in all groups compared with those at 2 weeks earlier, which may be related to the enhancement of background fluorescence due to the increases of collagen fibres in the tissues.

Masson’s staining was used to assess the deposition of collagen fibers during defect repair (Figure 9). At 2 and 4 weeks post surgery, collagen fibers significantly deposed over time in the penile interstitium of groups A and B. The area of collagen fibers in group A was (14.56±0.29)×106 pixels/HPF, is the highest among those groups at each time points (2 and 4 weeks post surgery) (Figure 7D).

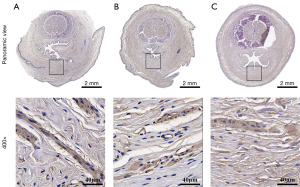

At 4 weeks postoperatively, the hyperplastic collagen tissue was analyzed by IHC staining, and assess the proliferation of α-SMA positive cells as well (Figure 10). At ×400 magnification, the cells in the penile interstitium of group A were organized and dense, and the mean area of reached (16.13±1.72)×105 pixels/HPF, which was significantly more hyperplastic compared to (13.42±1.27)×105 pixels/HPF in group B and (13.70±3.51)×105 pixels/HPF in group C (Figure 7E) (A to B, P=0.006; A to C, P=0.002).

Discussion

Urethral reconstruction is to restore urethral continuity by harvesting tissue from adjacent or other areas and shaping it for the urethra disorder treatment. It is used to repair or replace urethral strictures or defects caused by congenital defects, trauma, inflammation, or surgery to restore normal urethral structure and function, and therefore improve the patient’s quality of life (24,25). Compared to flaps and skin grafts, buccal mucosa has thicker epithelial cells, and grafting buccal mucosa for urethral reconstruction has been used successfully in clinical practice, showing higher success rates and patient satisfaction during phase I and multi-stage repairs (26-28). However, patients may experience complications such as pain, numbness, and postoperative scar contracture after a portion of the buccal mucosa is removed (29). Based on the available literature, multiple regimens using scaffolds and cells alone or in combination have achieved short-term success in animals or small human trials, but none have matured in the clinic (30-34). The development of urethral replacements with adequate strength, rapid functional recovery, and tissue regeneration rates is a long-term clinical goal (35).

Tilapia skin, as a natural biomaterial, has been gaining attention in recent years in the field of TE. It is rich in collagen and other bioactive components, as well as having excellent biocompatibility, and is therefore considered an ideal natural scaffold material (36,37). In TE, tilapia skin is often used as a three-dimensional scaffold for cell culture to provide space for cell growth and differentiation (18). Tilapia skin has now been successfully used for regeneration and repair of tissues such as skin, cartilage and bone (38). The residual nucleic acid in the tilapia skin is a potential antigen that can cause rejection, and there is still the possibility of sensitization or immune rejection, which poses a potential risk of clinical use and cannot meet the basic requirements for pre-market approval and regulation, and therefore it is necessary to remove it by decellularization technology. SIS has been considered as a promising biological scaffold due to its excellent biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, good mechanical property, and biodegradability. Therefore, SIS was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for urogenital surgery (39). It was initially reported as an almost-acellular material (40). However, further studies have shown porcine cells inside, which may cause inflammatory response after in vivo implantation which is in line with our results as shown in H&E image (Figure 6A). The DNA content in the DTS used in this experiment was 38.78±5.84 ng/mg which may effectively help avoid immune rejection during urethral reconstruction. We lyophilized and sterilized DTS to prolong the shelf-life and avoid soft tissue infections after implantation without changing the physicochemical properties of DTS as much as possible (18,41). By comparing the physical characterization of DTS with that of SIS, we found that DTS possessed a looser three-dimensional micropore structure (Figure 3) than that of SIS, and this is essential as a scaffold for cell migration and proliferation during the repair process. In addition, it also results in large deformation under stretching and exhibits good ductility (Figure 4). Under electron microscopy, its loose three-dimensional pore structure is a scaffold for the tissue to provide cell proliferation during the repair process. At 4 weeks postoperatively, DTS had fully fused with the penile tissue, while some obvious residues were still visible in the SIS patch. This result is agreed with the dense structure of SIS which may attenuates the water molecules infiltration. Angiogenesis is critical for the survival of implant as de novo blood vessel will provide nutrients and oxygen for cells proliferation and tissue growth. Our results in Figure 6 are in line with previous reports in which they concluded that the neovascularization induced by decellularized tissue is the key factor to promote de novo tissue growth and wound healing as well (21,22).

Nature of collagen renders DTS to inherent the advantages of low cytotoxicity, low immunogenicity, guiding the regeneration of cells, and good compatibility with the human body. After degradation, it can promote the deposition of collagen in the tissues. Collagen, as a major component of the ECM, and collagen deposition can be used to assess the effectiveness of wound healing (42). As shown in Figure 9, the area of collagen fiber in the DTS group were significantly higher than those in the SIS group and the control group. Compared with the sparse tissue structure in the control group, the deposited collagen made the tissue structure of the ventral side of the penis strengthened, which could effectively prevent the occurrence of complications such as urethral fistula. As shown in SEM, DTS has a regular and dense microporous and layered structure, which provides a scaffold for cells to anchor and grow in one way, while ensuring water vapor permeability and water absorption, and providing suitable conditions for postoperative wound wet healing in another way. In addition, while promoting urethral tissue repair, DTS has a thickness of 0.39±0.04 mm, which acts as a physical barrier to the external environment, blocking bacterial invasion and preventing postoperative wound infection (38).

TNF-α is a central regulator of inflammatory cascade and associated with inflammatory mechanisms related to implantation. Implants coated with TNF-α inhibitor could lead to significantly higher vessel densities, suggesting improved biocompatibility of implants (43). Overproduction of TNF-α is thought to affect wound healing through wound strength due to decreased collagen type I and type III expression (44). Collagen obtained by hydrolysis with different proteases usually possesses various biological activities such as antioxidant, bacteriostatic and immunomodulatory. This may be the reason why the degree of inflammatory response during DTS repair was significantly lower than that in the SIS and control groups. It can also be observed that a large number of inflammatory cells infiltration was seen around the postoperative SIS patch in the SIS group, which may be related to the fact that some porcine-derived cells still remained in the SIS thus leading to local inflammatory reactions after implantation in the animal and affecting the effect of urethral tissue repair (39). In addition, smooth muscle stain positive cell proliferation was more pronounced in urethral tissues after the application of DTS compared to SIS. It has been pointed out that collagen also retains, stores and transports growth factors, and plays an important role in cell proliferation and angiogenesis during tissue growth and repair (45-47).

To date, decellularized porcine and bovine skin have been developed into medical devices successfully used in the repair of clinically refractory wounds, and their function in promoting tissue regeneration and wound healing has been clinically proven (48). The use of decellularized matrix materials origin from porcine and bovine may be restricted due to the risk of zoonotic disease transmission such as mad cow disease and foot and mouth disease, coupled with religious factors (49). In the meantime, several studies have shown that marine animal collagen is a promising alternative due to its safety profile (17,41,50,51). Fish collagen has been shown to have several biological benefits, including immunomodulation, anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties, and promoting wound healing (52-54). Today, decellularized matrix products are relatively expensive, and the skin of tilapia, one of the most extensively farmed fish in the world, is disposed of as a waste resource in fish processing, generating tens of thousands of tons of waste yearly. The structure of fish skin is similar to that of mammalian skin and religious ethical barriers can be effectively circumvented.

Therefore, the DTS matrix is expected to be an alternative for decellularized matrix from terrestrial animals for soft tissue repair. The limitation of this study is that we were not able to test the repaired urethra for erectile function, uroflowmetry, and excretory urethrography, but we did not find that the rabbits had severe urinary difficulties during the experiment. Regarding larger defects, a potential limitation of DTS could be its relatively slower neovascularization rate compared with that of smaller defects. In larger defects, the diffusion distance of nutrients and oxygen from the surrounding tissues is longer than in small defects. Another limitation might be related to the mechanical properties of the DTS. In larger defects, similar to other rigid or elastic biomaterials, DTS may not provide adequate long-term mechanical support. However, we are currently exploring methods such as the crosslinking of collagen fibers in DTS, to modify DTS and improve its mechanical properties for better performance in larger urethral defect repair.

Conclusions

In the present study, we successfully prepared a marine acellular dermal matrix material, DTS, and used it in a rabbit urethral defect model for repair. Compared with the repairing effect of SIS, the tissue collagen and smooth muscle content were significantly increased and the inflammatory response was milder during the urethral defect healing with DTS. As a TE material of marine animal origin with no religious restrictions, DTS is expected to be used in clinical urethral reconstruction due to its effective effect on defect healing and histocompatibility in future.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the ARRIVE reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-598/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-598/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-598/prf

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-598/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Experiments were performed under a project license (No. wydw-2022-0463) granted by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee at Wenzhou Medical University, in compliance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guidelines for the care and use of animals.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Osman NI, Hillary C, Bullock AJ, et al. Tissue engineered buccal mucosa for urethroplasty: progress and future directions. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2015;82-83:69-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro-Filho LA, Sievert KD. Acellular matrix in urethral reconstruction. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2015;82-83:38-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verla W, Oosterlinck W, Spinoit AF, et al. A Comprehensive Review Emphasizing Anatomy, Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Male Urethral Stricture Disease. Biomed Res Int 2019;2019:9046430. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Ma W, Liu B, et al. Urethral reconstruction with autologous urine-derived stem cells seeded in three-dimensional porous small intestinal submucosa in a rabbit model. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017;8:63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Huang L, Yuan W, et al. Sustained release of stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha from silk fibroin microfiber promotes urethral reconstruction in rabbits. J Biomed Mater Res A 2020;108:1760-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barbagli G, Kulkarni SB, Fossati N, et al. Long-term followup and deterioration rate of anterior substitution urethroplasty. J Urol 2014;192:808-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Du A, Li J, et al. Development of a cell-seeded modified small intestinal submucosa for urethroplasty. Heliyon 2016;2:e00087. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pastorek D, Culenova M, Csobonyeiova M, et al. Tissue Engineering of the Urethra: From Bench to Bedside. Biomedicines 2021;9:1917. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adamowicz J, Kuffel B, Van Breda SV, et al. Reconstructive urology and tissue engineering: Converging developmental paths. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2019;13:522-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ortac M, Ekerhult TO, Zhao W, et al. Tissue Engineering Graft for Urethral Reconstruction: Is It Ready for Clinical Application? Urol Res Pract 2023;49:11-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chepelova N, Sagitova G, Munblit D, et al. The search for an optimal tissue-engineered urethra model for clinical application based on preclinical trials in male animals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bioeng Transl Med 2024;9:e10700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan Q, Le H, Tang C, et al. Tailor-made natural and synthetic grafts for precise urethral reconstruction. J Nanobiotechnology 2022;20:392. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chapple C. Tissue engineering of the urethra: where are we in 2019? World J Urol 2020;38:2101-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mandal TK, Dhanuka S, Choudhury S, et al. Tissue engineered indigenous pericardial patch urethroplasty: A promising solution to a nagging problem. Asian J Urol 2020;7:56-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El-Rashidy AA, Gad A. Chemical and biological evaluation of Egyptian Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticas) fish scale collagen. Int J Biol Macromol 2015;79:618-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Menezes MDLLR, Ribeiro HL, Abreu FOMDS, et al. Optimization of the collagen extraction from Nile tilapia skin (Oreochromis niloticus) and its hydrogel with hyaluronic acid. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2020;189:110852. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lv K, Wang L, He X, et al. Application of Tilapia Skin Acellular Dermal Matrix to Induce Acute Skin Wound Repair in Rats. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022;9:792344. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lau CS, Hassanbhai A, Wen F, et al. Evaluation of decellularized tilapia skin as a tissue engineering scaffold. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2019;13:1779-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang S, Lu X, Chen J, et al. Promotion of angiogenesis and suppression of inflammatory response in skin wound healing using exosome-loaded collagen sponge. Front Immunol 2024;15:1511526. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Wang Z, Dong Y. Collagen-Based Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2023;9:1132-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Li Z, Zheng Y, et al. 3D-printed dermis-specific extracellular matrix mitigates scar contraction via inducing early angiogenesis and macrophage M2 polarization. Bioact Mater 2021;10:236-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen L, Ma J, Chen Y, et al. Polydopamine modified acellular dermal matrix sponge scaffold loaded with a-FGF: Promoting wound healing of autologous skin grafts. Biomater Adv 2022;136:212790. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crapo PM, Gilbert TW, Badylak SF. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials 2011;32:3233-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni S, Joshi PM, Bhadranavar S. Advances in urethroplasty. Med J Armed Forces India 2023;79:6-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang B, Lv X, Li Z, et al. Urethra-inspired biomimetic scaffold: A therapeutic strategy to promote angiogenesis for urethral regeneration in a rabbit model. Acta Biomater 2020;102:247-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wessells H, Angermeier KW, Elliott S, et al. Male Urethral Stricture: American Urological Association Guideline. J Urol 2017;197:182-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zinman L. Muscular, myocutaneous, and fasciocutaneous flaps in complex urethral reconstruction. Urol Clin North Am 2002;29:443-66. viii. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santiago JE, Gross MD, Accioly JP, et al. Decision regret and long-term success rates after ventral buccal mucosa graft urethroplasty. BJU Int 2025;135:303-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao X, Guo Q, Zhang X, et al. The urinary and sexual outcomes of buccal mucosal graft urethroplasty versus end-to-end anastomosis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sex Med 2024;12:qfae064. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hua Y, Wang K, Huo Y, et al. Four-dimensional hydrogel dressing adaptable to the urethral microenvironment for scarless urethral reconstruction. Nat Commun 2023;14:7632. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Zhu Z, Liu Y, et al. Double-Modified Bacterial Cellulose/Soy Protein Isolate Composites by Laser Hole Forming and Selective Oxidation Used for Urethral Repair. Biomacromolecules 2022;23:291-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shebl SE, Akl MM, Abdalrazek M. Buccal versus skin graft for two-stage repair of complex hypospadias: an Egyptian center experience. BMC Urol 2022;22:115. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paramasivam T, Maiti SK, Palakkara S, et al. Effect of PDGF-B Gene-Activated Acellular Matrix and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation on Full Thickness Skin Burn Wound in Rat Model. Tissue Eng Regen Med 2021;18:235-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao Y, Peng H, Sun L, et al. The application of small intestinal submucosa in tissue regeneration. Mater Today Bio 2024;26:101032. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang C, Chen C, Guo M, et al. Stretchable collagen-coated polyurethane-urea hydrogel seeded with bladder smooth muscle cells for urethral defect repair in a rabbit model. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2019;30:135. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin HK, Madihally SV, Palmer B, et al. Biomatrices for bladder reconstruction. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2015;82-83:47-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jin Y, Yang M, Zhao W, et al. Scaffold-based tissue engineering strategies for urethral repair and reconstruction. Biofabrication 2024;17: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lima Verde MEQ, Ferreira-Júnior AEC, de Barros-Silva PG, et al. Nile tilapia skin (Oreochromis niloticus) for burn treatment: ultrastructural analysis and quantitative assessment of collagen. Acta Histochem 2021;123:151762. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casarin M, Fortunato TM, Imran S, et al. Porcine Small Intestinal Submucosa (SIS) as a Suitable Scaffold for the Creation of a Tissue-Engineered Urinary Conduit: Decellularization, Biomechanical and Biocompatibility Characterization Using New Approaches. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:2826. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng MH, Chen J, Kirilak Y, et al. Porcine small intestine submucosa (SIS) is not an acellular collagenous matrix and contains porcine DNA: possible implications in human implantation. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2005;73:61-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li D, Sun WQ, Wang T, et al. Evaluation of a novel tilapia-skin acellular dermis matrix rationally processed for enhanced wound healing. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2021;127:112202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karoud W, Ghlissi Z, Krichen F, et al. Oil from hake (Merluccius merluccius): Characterization, antioxidant activity, wound healing and anti-inflammatory effects. J Tissue Viability 2020;29:138-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hussain T, Gellrich D, Siemer S, et al. TNF-α-Inhibition Improves the Biocompatibility of Porous Polyethylene Implants In Vivo. Tissue Eng Regen Med 2021;18:297-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu R, Bal HS, Desta T, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates diabetes-enhanced apoptosis of matrix-producing cells and impairs diabetic healing. Am J Pathol 2006;168:757-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Pei X, Liu H, et al. Extraction and characterization of acid-soluble and pepsin-soluble collagen from skin of loach (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus). Int J Biol Macromol 2018;106:544-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharif S, Ai J, Azami M, et al. Collagen-coated nano-electrospun PCL seeded with human endometrial stem cells for skin tissue engineering applications. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2018;106:1578-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kandhasamy S, Perumal S, Madhan B, et al. Synthesis and Fabrication of Collagen-Coated Ostholamide Electrospun Nanofiber Scaffold for Wound Healing. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2017;9:8556-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petrie K, Cox CT, Becker BC, et al. Clinical applications of acellular dermal matrices: A review. Scars Burn Heal 2022;8:20595131211038313. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim YS, Ok YJ, Hwang SY, et al. Marine Collagen as A Promising Biomaterial for Biomedical Applications. Mar Drugs 2019;17:467. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun L, Li B, Song W, et al. Comprehensive assessment of Nile tilapia skin collagen sponges as hemostatic dressings. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2020;109:110532. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ge B, Wang H, Li J, et al. Comprehensive Assessment of Nile Tilapia Skin (Oreochromis niloticus) Collagen Hydrogels for Wound Dressings. Mar Drugs 2020;18:178. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elbialy ZI, Atiba A, Abdelnaby A, et al. Collagen extract obtained from Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) skin accelerates wound healing in rat model via up regulating VEGF, bFGF, and α-SMA genes expression. BMC Vet Res 2020;16:352. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Elango J, Wang S, et al. Characterization of Immunogenicity Associated with the Biocompatibility of Type I Collagen from Tilapia Fish Skin. Polymers (Basel) 2022;14:2300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laasri I, Bakkali M, Mejias L, et al. Marine collagen: Unveiling the blue resource-extraction techniques and multifaceted applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2023;253:127253. [Crossref] [PubMed]