Association between the American Heart Association’s new “Life’s Essential 8” metrics and urinary incontinence: a cross-sectional study of NHANES data from 2011 to 2018

Highlight box

Key findings

• Better body mass index and activity status are two key preventing factors for urinary incontinence (UI).

What is known and what is new?

• The American Heart Association introduced the concept of ideal cardiovascular health (CVH) and established the Life’s Essential 8 (LE8) score to reduce the risk of cardiovascular mortality.

• To our knowledge, our current study is the first to confirm that LE8 is significantly associated with the incidence of UI.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• This result challenges clinical and public health professionals to continue guiding health indicators in a positive direction. Looking ahead, we can aim to achieve or maintain higher CVH levels by controlling body weight and increasing physical activity, thereby reducing the incidence of cardiovascular diseases and UI. This reduction would likely lead to decreased healthcare costs and a diminished social burden.

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs) refer to a group of symptoms related to urinary retention, micturition, and post-micturition, as defined by the International Continence Society (ICS). The common symptoms of LUTS include urgency, frequency, nocturia, and urinary incontinence (UI). Particularly, UI has been shown to negatively affect both physical and mental health (1-3). Women in the United States are reported to spend more than $12 billion annually on treatment and care for stress urinary incontinence (SUI), which is a tremendous burden on the healthcare system (4).

UI is the involuntary loss of urine from the bladder (5). Currently, the ICS and International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) categorize UI into the following three types: SUI, urge urinary incontinence (UUI) and mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) (6). SUI is defined as “the involuntary leakage from the urethra occurring synchronously with effort, physical exertion, or during sneezing or coughing”. UUI is defined as “a complaint of involuntary urine loss associated with urgency, typically observed in the context of overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome”. Lastly, MUI is defined as “a complaint of involuntary urine loss associated with both urgency and effort, physical exertion, or sneezing or coughing” (7).

A few risk factors are associated with UI, including age, body mass index (BMI), race, smoking, depression and so on. Previous research has revealed that the prevalence of UI increases dramatically with age and BMI, and has a notable impact on patients’ quality of life (8,9). Furthermore, there is a wider range of potential risk factors, such as various cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) that have been demonstrated to increase the incidence of UI (10).

Initially, the American Heart Association (AHA) defined the notion of cardiovascular health (CVH) and quantified CVH into seven desirable metrics to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death (11). With extensive research, the AHA updated the CVH scale to include eight metrics in the following areas: diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, sleep health, BMI, lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure, known collectively as the “Life’s Essentials 8” (LE8) metrics (12). And it has been demonstrated that the application of an ideal CVH status can reduce the risk of kidney stones, sarcopenia and type 2 diabetes in these patients, in addition to improving the poor prognosis of patients with CVD (13,14). However, the relationship between optimum CVH state and the risk of UI incidence has not been clarified.

Therefore, the current study sought to investigate the relationship between ideal CVH status as rated by LE8 score and the occurrence of UI in American adults, to provide guidance for UI prevention. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2024-649/rc).

Methods

Participant details

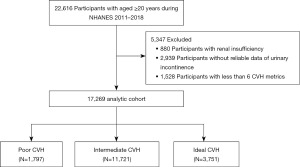

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is an ongoing, nationally representative, two-year cross-sectional survey designed and administered by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). It collects demographic, socioeconomic, nutritional, and health-related data from the United States and uses a combination of interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory tests to assess the health and nutritional status of the U.S. household population. The data are available on the website of the America Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm). Notably, the study protocol was approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board. All individuals gave written consent at the time of recruitment. 2011-2018 Patients’ basic information was derived from data file named as DEMO_G, DEMO_H DEMO_I and DEMO_J. As illustrated in Figure 1, this study comprised people aged ≥20 years who were joined in NHANES 2011–2018 (n=22,616). Of these participants, 5,347 were removed due to the following criteria: (I) renal insufficiency; (II) unreliable data of UI; and (III) insufficient data to calculate the CVH scores (less than 6 CVH metrics). Therefore, 17,269 participants were finally enrolled in the current study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

UI history

The information about urinary symptoms of 2011–2018 patients was acquired from data file KIQ_U_G, KIQ_U_H, KIQ_U_I, KIQ_U_J. Symptoms of UI were measured with the variables tagged as KIQ005 (how often have urinary leakage?), KIQ010 (How much urine lose each time?), KIQ042 (Leak urine during physical activities?), KIQ046 (Leak urine during nonphysical activities?) and KIQ480 (How many times urinate in night?).

CVH metrics

The CVH metrics encompass four health behaviors (diet, physical activity, nicotine exposure, and sleep) and four health factors (BMI, lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure) (11). The Healthy Eating Index 2015 (HEI-2015) score, which functioned as a proxy for the Healthy Eating Score and was determined using a 24-hour dietary recall from the first day. It is a dietary assessment tool comprising 13 components that are combined to give a total score of 100, with higher scores reflecting a healthier diet. To determine sleep health, objective sleep data from wearable devices were utilized to determine the average number of hours of sleep and calculate a score. Nicotine exposure was measured through self-reported usage of cigarettes or electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS); the adverse health effects of secondhand smoke were also included in the score. Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) or fasting blood glucose was used as the glycemic score. All participants had a history of diabetes prior to assessment. Non-high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, but not total cholesterol (TC), was used to measure blood lipids, and the BMI was computed by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared. The mean blood pressure was estimated using three standardized readings made during a medical examination.

Variables of interest

Age, sex, and race were self-reported. We utilized the CVH for our analysis, which was determined based on the definition of the AHA LE8 score and the scoring methodology for quantifying the CVH (12). Participants were given a calculated score of 0–100 for each CVH indicator, and the total CVH score was determined as the unweighted mean of all 8 metrics, ranging from 0 to 100. Participants with an average score of 0–49, 50–79, or 80–100 were categorized as having poor, intermediate, or ideal CVH, respectively.

Statistical analysis

We performed all statistical analyses according to CDC guidelines and used NHANES-recommended weights to account for program oversampling in specific groups. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were represented as counts plus percentages. The baseline characteristics across the 3 CVH groups were compared using the t-test for continuous variables and the Chi-squared test for categorical variables. To analyze the association between CVH metrics and UI, logistic regression analyses were performed using a crude model and two adjusted models: Model 1 was a crude model without adjustment; Model 2 was adjusted for age and gender; and Model 3 was adjusted for age, gender, and race. The strength of correlations was estimated by odds ratios (ORs) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) and weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression were utilized to perform the aggregate effect and principal component analysis, which help us determine which of the 8 factors are the key factors affecting the UI. All data analyses were performed using survey package in R software (version 4.0.4; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in (Table 1, available online: https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/tau-2024-649-1.xlsx). The average age of the 17,269 participants in this study was 49.21±17.62 years, and 50.29% of the participants were female. Among the 17,269 participants, a total of 2,335 (13.5%) were Mexican American, 2,056 (11.9%) were non-Hispanic Asian, 3,868 (22.4%) were non-Hispanic Black, 6,571 (38.1%) were non-Hispanic White and 1,798 (10.4%) were other Hispanic. The proportions of poor, intermediate, and ideal CVH were 10.41%, 67.87%, and 21.72%, respectively. In the present study, the probability of UI in participants with poor, intermediate, and ideal CVH was 40.7%, 30.7%, and 21.7%, respectively, and the probability of UI at rest was 13.0%, 8.7%, and 5.2%, respectively. In addition, the probability of night urination (including voluntary urination) in these participants was 79.1%, 71.7%, and 61.1%, respectively. Evidently, participants with poor CVH were two times more likely to experience UI than those with ideal CVH.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Total (n=17,269) | Poor CVH (n=1,797) | Intermediate CVH (n=11,721) | Ideal CVH (n=3,751) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.21 (17.62) | 51.95 (15.42) | 51.00 (17.40) | 42.30 (17.56) | <0.001 |

| Gender (female) | 8,685 (50.3) | 928 (51.6) | 5,696 (48.6) | 2,061 (54.9) | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||

| Mexican American | 2,335 (13.5) | 245 (13.6) | 1,687 (14.4) | 403 (10.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 2,056 (11.9) | 65 (3.6) | 1,202 (10.3) | 789 (21.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3,868 (22.4) | 617 (34.3) | 2,640 (22.5) | 611 (16.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 6,571 (38.1) | 615 (34.2) | 4,479 (38.2) | 1,477 (39.4) | |

| Other Hispanic | 1,798 (10.4) | 158 (8.8) | 1,281 (10.9) | 359 (9.6) | |

| Other race | 641 (3.7) | 97 (5.4) | 432 (3.7) | 112 (3.0) | |

| Marriage | <0.001 | ||||

| Divorced | 1,891 (11.0) | 293 (16.3) | 1,346 (11.5) | 252 (6.7) | |

| Living with partner | 1,502 (8.7) | 186 (10.4) | 996 (8.5) | 320 (8.5) | |

| Married | 8,693 (50.3) | 698 (38.8) | 6,010 (51.3) | 1,985 (52.9) | |

| Never married | 3,394 (19.7) | 358 (19.9) | 2,038 (17.4) | 998 (26.6) | |

| Refused | 7 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 4 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | |

| Separated | 568 (3.3) | 89 (5.0) | 407 (3.5) | 72 (1.9) | |

| Widowed | 1,214 (7.0) | 171 (9.5) | 920 (7.8) | 123 (3.3) | |

| Leakage frequency | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | 12,120 (70.2) | 1,066 (59.3) | 8,117 (69.3) | 2,937 (78.3) | |

| Less than once a month | 1,600 (9.3) | 170 (9.5) | 1,093 (9.3) | 337 (9.0) | |

| A few times a month | 1,642 (9.5) | 221 (12.3) | 1,166 (9.9) | 255 (6.8) | |

| A few times a week | 917 (5.3) | 139 (7.7) | 650 (5.5) | 128 (3.4) | |

| Every day and/or night | 990 (5.7) | 201 (11.2) | 695 (5.9) | 94 (2.5) | |

| Leakage amount | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 12,120 (70.2) | 1,066 (59.3) | 8,117 (69.3) | 2,937 (78.3) | |

| Drops | 3,586 (20.8) | 448 (24.9) | 2,520 (21.5) | 618 (16.5) | |

| Small splashes | 1,046 (6.1) | 184 (10.2) | 712 (6.1) | 150 (4.0) | |

| More | 517 (3.0) | 99 (5.5) | 372 (3.2) | 46 (1.2) | |

| Leak at rest | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 15,826 (91.6) | 1,564 (87.0) | 10,706 (91.3) | 3,556 (94.8) | |

| Yes | 1,443 (8.4) | 233 (13.0) | 1,015 (8.7) | 195 (5.2) | |

| Night urinates | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | 5,158 (29.9) | 376 (20.9) | 3,321 (28.3) | 1,461 (38.9) | |

| 1 time per night | 6,602 (38.2) | 577 (32.1) | 4,512 (38.5) | 1,513 (40.3) | |

| 2 times per night | 3,206 (18.6) | 414 (23.0) | 2,264 (19.3) | 528 (14.1) | |

| 3 times per night | 1,484 (8.6) | 249 (13.9) | 1,062 (9.1) | 173 (4.6) | |

| 4 times per night | 493 (2.9) | 103 (5.7) | 344 (2.9) | 46 (1.2) | |

| 5 times or more per night | 326 (1.9) | 78 (4.3) | 218 (1.9) | 30 (0.8) | |

| BMI score | 59.33 (34.01) | 31.51 (29.71) | 55.18 (32.81) | 85.61 (20.61) | <0.001 |

| Smoking score | 72.42 (39.37) | 35.67 (42.75) | 71.20 (39.37) | 93.77 (17.81) | <0.001 |

| Diet score | 51.13 (26.31) | 31.12 (22.60) | 49.00 (24.88) | 67.37 (23.23) | <0.001 |

| Activity score | 64.93 (37.13) | 41.07 (38.60) | 62.82 (37.90) | 80.39 (26.30) | <0.001 |

| Lipid score | 86.11 (23.19) | 70.62 (28.99) | 84.45 (23.97) | 94.97 (14.24) | <0.001 |

| Glucose score | 71.8 (30.18) | 39.89 (34.45) | 68.55 (29.33) | 90.35 (17.59) | <0.001 |

| Blood pressure score | 69.56 (31.61) | 45.37 (31.27) | 66.58 (31.16) | 90.48 (18.76) | <0.001 |

| Sleep score | 81.68 (25.20) | 61.61 (30.84) | 81.41 (24.77) | 92.07 (15.87) | <0.001 |

| CVH | 68.75 (58.33, 78.12) | 44.00 (39.00, 47.50) | 66.67 (59.38, 72.50) | 85.00 (82.14, 90.00) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean (SD), median (IQR) or n (%). BMI, body mass index; CVH, cardiovascular health; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Association between CVH score and UI in logistic model

Ideal CVH was associated with a reduced incidence of UI compared with poor CVH in the crude model (OR: 0.404, 95% CI: 0.358–0.457, P<0.001; Table 2). After the adjustment for age, sex, and race, ideal CVH was still associated with a reduced incidence of UI compared with poor CVH (adjusted OR: 0.495, 95% CI: 0.432–0.567, P<0.001).

Table 2

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||

| Poor CVH | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||||

| Intermediate CVH | 0.647 (0.585–0.717) | <0.001 | 0.640 (0.572–0.715) | <0.001 | 0.650 (0.581–0.728) | <0.001 | ||

| Ideal CVH | 0.404 (0.358–0.457) | <0.001 | 0.473 (0.414–0.540) | <0.001 | 0.495 (0.432–0.567) | <0.001 | ||

Model 1: crude; Model 2: adjusted age, sex; Model 3: adjusted age, sex, race. CVH, cardiovascular health; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Association between individual CVH components and UI occurrence

In sensitivity analyses, the WQS model revealed the weighted values of each CVH metric for UI. Models were adjusted for sex, age, race, education, family income-to-poverty ratio, marital status. Notably, BMI and activity score accounted for the largest proportion of the overall effect, both reaching more than 30%, suggesting that these two factors are the key factors affecting UI in LE8 (Figure 2). The BKMR model also showed an overall positive association of high LE8 score with the prevention of UI, although this association is that significant (Figure 3A). Moreover, mixture effect analysis particularly pointed out that BMI and physical activity are the two key preventing factors for UI, which is parallel with the WQS analysis (Figure 3B,3C), whereas the effects of the other metrics were not apparent. After further adjusting for age, gender, and race of the participants, the results did not substantially change.

Discussion

Over 200 million people in the world are suffering from UI to various degrees (15). Most of them are women, with the prevalence of UI ranging from 15% to 52% (16), and the incidence of UI is rising with the aging of the population, exerting a substantial burden on patients, their families, and society (9,17). Nevertheless, despite the huge number of patients, relatively few of them actually seek medical attention and receive standardized treatment (9). One reason for this is that they do not consider UI as a life-threatening condition, hence they rarely treat it as a health problem. According to Wong’s study, 60.6% of women believed that “UI is normal” and 78.3% of women with UI believed that “UI is not a disease” (18). This makes us realize that we should treat this disease from the perspective of prevention rather than cure. Moreover, little is known about UI, and few large studies have been able to identify risk factors by linking their data to patient medical outcomes. Therefore, there is an urgent need to raise public awareness of UI and spare no effort to increase the rate of patient presentation and standardized treatment.

In recent years, the AHA has introduced the concept of CVH and updated CVH as eight ideal indicators to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death. Interestingly, more and more studies have found that CVH is associated with a variety of other diseases in addition to CVD. Previously, Tennstedt et al. reported that CVD was one of the co-morbid risk factors for UI and that a variety of CVD increased the incidence of UI (10). White men with UI were more than 4 times more likely to have heart disease, while women with heart disease were 2.5 times more likely to have UI, as were black women and Hispanic women with hyperlipidemia (10). This led us to wonder if CVH was associated with UI. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to show that the AHA’s new “Essential 8” metric has a substantial relationship with the incidence of UI. This study analyzed cross-sectional data from the NHANES to show a substantial relationship between CVH and UI, revealing that people with perfect CVH parameters had a significantly decreased adjusted risk of UI. After accounting for relevant confounders, higher and optimal CVH remained favorably related with a lower incidence of UI.

Among the eight metrics in “LE8”, each is significantly associated with UI or its types. First, current research indicates that a high intake of numerous nutrients is not significantly associated with SUI or MUI. However, low-carbohydrate and high-protein diets may increase the risk of UUI in postmenopausal women (19). A high-protein diet may induce osmotic diuresis, a mechanism that could lead to urine accumulation in the bladder, thereby increasing the risk of UI (19,20). Second, numerous studies have demonstrated that women who engage in higher levels of physical activity report lower prevalence rates of UI (10,21). Bauer et al. found a significant association between higher levels of overall physical activity and both UUI and MUI in postmenopausal women, but no significant relationship with SUI (19). Third, Abufaraj et al. found a higher prevalence of UUI among women who smoke (22). This finding suggests that smoking may be a potential risk factor for UUI, thus warranting further investigation into its mechanisms. Fourth, studies have shown a significant correlation between sleep duration and UI, demonstrating a U-shaped nonlinear relationship (23). Sleep deprivation or excessive sleepiness may increase the risk of UUI and MUI (24). Additionally, research indicates that patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), both male and female, have a significantly higher prevalence of UI. The occurrence of OSA is closely related to an increased risk of SUI, UUI, and MUI (25). Fifth, a higher BMI is significantly associated with the prevalence of all types of UI, and this association is at least twice as strong. Specifically, the incidence of SUI increases with age. Among women aged 40 to 59 years, the prevalence of SUI is 51.3%, rising to 53.1% in women over 60 years (22). This trend indicates that BMI and age are important factors influencing the occurrence of UI. Sixth, hyperlipidemia has been shown to be associated with the risk of SUI in obese women (26). Epidemiological studies indicate that hyperlipidemia is not only a risk factor for white matter hyperintensity and OAB syndrome, but may also lead to UI (27,28). Among these, fasting serum triglycerides (TG) are the blood lipid indicators most closely related to the risk of SUI, particularly prominent in obese women under 50 years old (26). Additionally, elevated serum TC, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) are associated with increased susceptibility to SUI in women, whereas elevated TG and insulin resistance may offer some protective effects against UI (29). Seventh, blood glucose and HbA1c levels are closely related to the occurrence of SUI and UUI. As the severity of UUI increases, blood glucose and HbA1c levels also rise accordingly. This makes these indicators effective markers for assessing the severity of SUI and UUI (30,31). Huang et al.’s research demonstrates that the combination of the triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) and BMI is more significantly associated with SUI in postmenopausal women, and this combined indicator holds high clinical value in diagnosing SUI (32). Finally, Scime et al. indicated that chronic diseases are closely related to the incidence of UI, particularly hypertension, which has a strong association with the occurrence of UI (33). However, due to the relatively few reports and unclear pathophysiological mechanisms, the relationship between hypertension and UI requires further research.

More importantly, we sought to determine the effect of each metric in CVH on the risk of UI in the present study. The results showed that BMI and physical activity were associated with a reduced risk of UI, whereas the effects of the other metrics were not evident. BMI is not surprising, as it has been previously reported that the prevalence of UI increases with growing BMI (9,34). BMI is a commonly cited risk factor for UI (2,34-37). Interestingly, recent studies have found that waist circumference appears to be more sensitive than BMI in interpreting the relationship between obesity and UI (35). Tennstedt et al. reported that for every 10 cm increase in a woman’s waist circumference, the odds of weekly UI increased by 15% (10). The reason for this is probably that abdominal circumference is an indirect measure of intra-abdominal pressure, and the accumulation of excess fat in the abdomen is more likely to directly increase pelvic pressure, which can lead to UI, than is a high BMI (38). Alarmingly, physical activity was not found to have a remarkable effect on the incidence of UI in previous studies (10). But in the present study, physical activity was found to be the second most important factor influencing the risk of UI. Wing et al. found that by treating UI using lifestyle improvements such as physical activity, the prevalence of UI significantly improved in women who lost 5% to 10% of their body weight (39). Hence, early intervention for weight loss through physical activity can be effective in preventing the onset and progression of UI (39,40).

Through this study, we sought to expand the understanding of the benefits associated with the application of CVH metrics. Specifically, our findings indicate that a higher number of moderate or optimal CVH metrics correlates with a lower incidence of UI. This result challenges clinical and public health professionals to continue guiding health indicators in a positive direction. Looking ahead, we can aim to achieve or maintain higher CVH levels by controlling body weight and increasing physical activity, thereby reducing the incidence of CVD and UI. This reduction would likely lead to decreased healthcare costs and a diminished social burden. Moreover, to enhance public awareness of CVH and improve population health, further research is warranted to explore additional associations between CVH and non-CVH outcomes.

Nevertheless, there are several limitations in this study. Firstly, information on nicotine exposure, physical activity, disease, and diet was self-reported and subject to misclassification and recall bias, which may have led to overestimation or underestimation of the association between CVH and UI. Moreover, the diagnosis of UI primarily depends on self-reported data and questionnaire-based information, which inherently introduces recall bias. Secondly, despite controlling for most potential confounders in the analysis, the NHANES database still has inherent limitations, leading to the presence of uncontrolled confounding factors. For instance, variables including the characteristics and severity of UI, individual lifestyle habits and their changes, and the progression of diseases were not thoroughly considered or controlled in this study. Thirdly, since our study was based on the NHANES database, the cross-sectional study design made it difficult to interpret causality, and thus the association between CVH and UI could not be interpreted as a direct causal relationship. Finally, these findings are from a national survey in America, which may affect the generalizability of our results and may not be applicable to populations of other races. Given the limitations of the current study, these results should be interpreted with caution, and further research is needed to support our findings.

Conclusions

In this retrospective cohort study, we discovered that adopting a healthy lifestyle based on CVH measures may minimize the risk of UI. Higher BMI or activity score are two key preventing factors for UI. Our analysis extends previous findings by suggesting that interventions to prevent CVD are also expected to prevent the occurrence of UI.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2024-649/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2024-649/prf

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2024-649/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement:

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Hung KJ, Awtrey CS, Tsai AC. Urinary incontinence, depression, and economic outcomes in a cohort of women between the ages of 54 and 65 years. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:822-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Minassian VA, Drutz HP, Al-Badr A. Urinary incontinence as a worldwide problem. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003;82:327-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pizzol D, Demurtas J, Celotto S, et al. Urinary incontinence and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021;33:25-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chong EC, Khan AA, Anger JT. The financial burden of stress urinary incontinence among women in the United States. Curr Urol Rep 2011;12:358-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2002;21:167-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doumouchtsis SK, de Tayrac R, Lee J, et al. An International Continence Society (ICS)/ International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) joint report on the terminology for the assessment and management of obstetric pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J 2023;34:1-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J 2010;21:5-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Q, Que YZ, Wan XY, et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Impact on Life of Female Urinary Incontinence: An Epidemiological Survey of 9584 Women in a Region of Southeastern China. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2023;16:1477-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baykuş N, Yenal K. Prevalence of urinary incontinence in women aged 18 and over and affecting factors. J Women Aging 2020;32:578-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tennstedt SL, Link CL, Steers WD, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for urine leakage in a racially and ethnically diverse population of adults: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:390-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 2010;121:586-613. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, et al. Life's Essential 8: Updating and Enhancing the American Heart Association's Construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022;146:e18-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dong X, Liao L, Wang Y, et al. Association between the American Heart Association's new "Life's Essential 8" metrics and kidney stone. World J Urol 2024;42:199. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen W, Shi S, Jiang Y, et al. Association of sarcopenia with ideal cardiovascular health metrics among US adults: a cross-sectional study of NHANES data from 2011 to 2018. BMJ Open 2022;12:e061789. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Norton P, Brubaker L. Urinary incontinence in women. Lancet 2006;367:57-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yip SK, Cardozo L. Psychological morbidity and female urinary incontinence. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007;21:321-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson L, Brown JS, Shin GP, et al. Annual direct cost of urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:398-406. [PubMed]

- Wong T, Lau BY, Mak HL, et al. Changing prevalence and knowledge of urinary incontinence among Hong Kong Chinese women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2006;17:593-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bauer SR, Kenfield SA, Sorensen M, et al. Physical Activity, Diet, and Incident Urinary Incontinence in Postmenopausal Women: Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2021;76:1600-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alwis US, Delanghe J, Dossche L, et al. Could Evening Dietary Protein Intake Play a Role in Nocturnal Polyuria? J Clin Med 2020;9:2532. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waetjen LE, Liao S, Johnson WO, et al. Factors associated with prevalent and incident urinary incontinence in a cohort of midlife women: a longitudinal analysis of data: study of women's health across the nation. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:309-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abufaraj M, Xu T, Cao C, et al. Prevalence and trends in urinary incontinence among women in the United States, 2005-2018. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021;225:166.e1-166.e12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen T, Zhan X, Xiao S, et al. U-shaped association between sleep duration and urgency urinary incontinence in women: a cross-sectional study. World J Urol 2023;41:2429-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nan X, Dai S, Zhao S, et al. The Interaction Effect of Obesity with Sleep Duration on Urinary Incontinence in Adult Females: A Cross-Sectional Study of the NHANES Database. Urol Int 2024;108:525-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li B, Li F, Xie X, et al. Associations between obstructive sleep apnea risk and urinary incontinence: Insights from a nationally representative survey. PLoS One 2024;19:e0312869. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu F, Chen M, Xiao Y, et al. Synergistic interaction between hyperlipidemia and obesity as a risk factor for stress urinary incontinence in Americans. Sci Rep 2024;14:7312. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu L, Yang L, Zhang X, et al. Age and recurrent stroke are related to the severity of white matter hyperintensities in lacunar infarction patients with diabetes. Clin Interv Aging 2018;13:2487-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chae J, Yoo EH, Jeong Y, et al. Risk factors and factors affecting the severity of overactive bladder symptoms in Korean women who use public health centers. Obstet Gynecol Sci 2018;61:404-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiang N, Su S, Yang Y, et al. Genetic support of causal association between lipid and glucose metabolism and stress urinary incontinence in women: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization and multivariable-adjusted study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024;15:1394252. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ying Y, Xu L, Huang R, et al. Relationship Between Blood Glucose Level and Prevalence and Frequency of Stress Urinary Incontinence in Women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2022;28:304-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu N, Xing L, Mao W, et al. Relationship Between Blood Glucose and Hemoglobin A1c Levels and Urinary Incontinence in Women. Int J Gen Med 2021;14:4105-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang X, Hu W, Li L. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and its correlation indexes and stress urinary incontinence in postmenopausal women: evidence from NHANES 2005-2018. Lipids Health Dis 2024;23:419. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scime NV, Hetherington E, Metcalfe A, et al. Association between chronic conditions and urinary incontinence in females: a cross-sectional study using national survey data. CMAJ Open 2022;10:E296-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Townsend MK, Danforth KN, Rosner B, et al. Body mass index, weight gain, and incident urinary incontinence in middle-aged women. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:346-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park S, Baek KA. Association of General Obesity and Abdominal Obesity with the Prevalence of Urinary Incontinence in Women: Cross-sectional Secondary Data Analysis. Iran J Public Health 2018;47:830-7. [PubMed]

- Mishra GD, Hardy R, Cardozo L, et al. Body weight through adult life and risk of urinary incontinence in middle-aged women: results from a British prospective cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1415-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weinberg AE, Leppert JT, Elliott CS. Biochemical Measures of Diabetes are Not Independent Predictors of Urinary Incontinence in Women. J Urol 2015;194:1668-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lambert DM, Marceau S, Forse RA. Intra-abdominal pressure in the morbidly obese. Obes Surg 2005;15:1225-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wing RR, Creasman JM, West DS, et al. Improving urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women through modest weight loss. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:284-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wing RR, West DS, Grady D, et al. Effect of weight loss on urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women: results at 12 and 18 months. J Urol 2010;184:1005-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]