Ejaculatory abstinence and its impacts on within- and between-individual variations in semen parameters of 9,595 Vietnamese men

Highlight box

Key findings

• In an individual, semen parameters remain unchanged between two samplings if ejaculatory abstinences (EAs) are kept identical.

• Straight-line velocity is not affected by EAs.

What is known and what is new?

• EA influences semen parameters, but the direction of these associations is inconsistent among previous studies, which mainly use the between-individual approach.

• The present study uses both within- and between-individual analyses to highlight the impact of EA on semen parameters.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• When re-evaluating a semen analysis, the abstinence period between two samples should remain consistent.

Introduction

As a principal laboratory examination used for investigating fecundity and testicular function, semen analysis has been studied for many years. Among proven factors that influence the result of semen analysis, ejaculatory abstinence (EA) is one of the significant confounders (1). Despite the importance of EA in interpreting semen analysis, most of the studies on men’s fertility have not considered its role (2). There are abundant shreds of evidence indicating the relationship between EA and not only conventional but also extended or advanced sperm parameters or pregnancy outcomes following assisted reproductive technologies (3-8). However, previous studies have not shown consistent correlations between EA and semen quantity and quality, even with fundamental parameters such as sperm concentration or proportion of total motility (3,4). Though the World Health Organization (WHO) has consistently recommended 2–7 days of abstinence as a standard for examining human semen (1,9), no persuasive evidence exists to confirm this suggestion (3). Whether semen parameters reach peaks at specific EA remains an unresolved question.

Moreover, semen parameters exhibit significant variation between subjects and over time (10). Thus, the within-individual analysis seems to provide more reliable information on the effect of EA on semen parameters rather than the between-individual approach (10). Unfortunately, studies controlling intrinsic factors are scarce, with relatively small observations that lead to controversial results (8,11-18). Furthermore, EA in every sampling used to be fixed at some limited time points, preventing the full assessment of the role of abstinence in variations of semen parameters. Indeed, there is a lack of studies testing the relationship between temporal EA deviation and semen parameters. In recent editions of the Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen, WHO continues to recommend doing the semen analysis twice to determine men’s baseline fertility accurately (1). However, it is essential to consider the potential impact of EA variation during result interpretation. The presented study aims to address the gap of knowledge regarding this relationship by revisiting the effect of EA on semen analysis in an extensively large sample size using both between-individual and within-individual approaches. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-553/rc).

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study retrieved medical records of patients who presented to Andrology and Sexual Medicine clinics in Hanoi Medical University Hospital from May 2017 to December 2022 for reproductive health check-ups. For these patients, the information related to medical history and sexual behaviors (relationship status, sexual partners, sex/masturbation frequency) was investigated before the physical examination. No sexual dysfunctions were noted. Men with genital abnormalities or severe health conditions that can affect sperm production, such as organic hypogonadism, varicocele, or malignant-related treatments (on chemotherapy or radiotherapy), will be excluded. Subsequently, hormonal profiles [luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), estradiol, and testosterone], testicular and abdominal ultrasound, and semen analysis were done to further evaluate fecundity. At the point of the first visit, fasting-state blood tests were performed before taking semen samples in the morning, and the pituitary-hypogonadism axis’s hormones were accessed using the electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) method with assays provided by Roche. In cases suspecting testosterone deficiency, the total testosterone would be re-examined in the second visit, and the average value would be reported. An abdominal ultrasound was performed to screen for abnormalities and measure prostate volume. Ultrasonic testicular volumes were measured and calculated using the fixed protocol provided in the previous study (19). This study uses retrospective data from medical records stored in Hanoi Medical University Hospital’s system. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by Hanoi Medical University ethics committee (HMUIRB#1829). Due to the study’s retrospective and cross-sectional design, individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived. The patient’s identity was kept confidential.

Semen was collected and prepared following principles of the World Health Organization laboratory manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen 5th edition [2010] (9). The sample was taken by masturbation in a quiet room without the partner’s involvement, which was not equipped with erotic materials. Indeed, whether or not using visual sexual stimulations during sampling would not affect the semen analysis and, thus, did not result in any concern (20). Semen samples were then stored in a sterile container at 20–37 ℃ and placed in an incubator (37 ℃) until liquefied. Firstly, semen volume was calculated based on the weight of the sample. Other parameters of consideration, including sperm concentration (×106/mL), total motility (%), and straight-line velocity (VSL) (µm/s), were analyzed by the Computer Aided Sperm Analysis (CASA) system of MTG-Germany under the strict supervision of a well-trained laboratory staff. Measurements were repeated in three fields where sperm concentration was not too dense. The average of these analyses was reported. Technicians reassessed the results achieved from CASA to minimize the overestimation. The manual procedure would be performed when concerning the accuracy of semen analysis by CASA, especially in cases of not fully semen liquefaction, very high sperm density, or too much debris and non-sperm fragments. Total motile sperm count (TMSC) (×106) was determined by multiplying the semen volume with sperm concentration and total motility. All results were stored and uploaded into the data storage system. For patients who had done the semen analysis twice, the interval between the first and the second sampling was less than 1 month without any intervention during this period. Men who reported more than 14 days of EA were excluded to minimize bias. Azoospermia was excluded since it may not be altered by extending the abstinence period.

The EA was defined as the number of days between the last ejaculation and the day of the semen sampling. It was noted as “<1 day” if the interval between two ejaculations is less than 24 hours. In this study, only semen analysis with no more than 14 days of abstinence was included to minimize recall bias. In cases of men performing two semen analyses, we labeled the EA of the visit in which patients had shorter abstinence as EAT1 (days), and the other with an identical or longer EA was designated as EAT2 (days). Thus, a two-time abstinence deviation (∆EAT2-T1) was calculated by using the longer abstinence minus the shorter abstinence. When abstinences of both times were identical, this variable was marked as “0”.

In this study, the relationship between the abstinence period and seminal profile was first explored by using all semen analyses. We then focused on the participants, who had two samples, to test whether the abstinence period truly affected the semen parameters when controlling all other factors.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata 15.1 software and the R program version 3.6.3 for Windows. Continuous variables were presented in mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and 5th–95th percentiles. Since all semen parameters did not follow the normal distribution according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test’s result, non-parametric tests were used to explore the data further. The difference between groups and whether increases in semen parameters followed the group order was investigated using Kruskal-Wallis and Cuzick’s rank-based nonparametric test for trends. The Dunn test with the Bonferroni adjustment was used in post hoc analyses. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for the paired difference between the longer vs. shorter abstinence presented in graphs. With the mixed data of all semen analyses, age-adjusted linear regressions were used to estimate relationships between the EA time and semen parameters. Several multivariate linear regression models were fitted using the backward stepwise approach to explain the variations between two ejaculations. The shorter abstinence (EAT1), the two-time abstinence deviation (∆EAT2-T1), and others (such as age, ejaculation frequency per week including both sexual intercourse and masturbation, hormonal profile, ultrasound testicular volume, and prostate volume) were used in unadjusted models before integrate in multivariate linear regressions. The P value at 0.05 was set as a statistically significant level.

Results

Among 9,595 men involved in this study, only 1,702 men had two records of the semen analysis, while the others did it once. When mixing all together, 11,297 semen analyses were used to investigate the between-individual variation in semen parameters regarding the abstinence period. Table 1 describes the seminal profiles of the whole study population and subgroup analyses.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Total (n=9,595) | One-time sampling (n=7,893) | Two-time sampling (n=1,702) | Mixed data (n=11,297) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAT1 | EAT2 | ||||

| Age (years) | 28.8±6.53; 28.0 (19.0, 40.0) | 28.7±6.61; 28.0 (19.0, 40.0) | 29.1±6.15; 29.0 (20.0, 40.0) | – | |

| LH (IU/L)† | 5.23±2.43; 4.85 (2.43, 9.18) | 5.25±2.43; 4.89 (2.45, 9.16) | 5.15±2.45; 4.70 (2.36, 9.31) | – | |

| FSH (IU/L)‡ | 4.60±2.79; 4.00 (1.80, 9.23) | 4.55±2.69; 3.98 (1.79, 9.01) | 4.81±3.15; 4.11 (1.85, 9.80) | – | |

| Total testosterone (nmol/L)§ | 17.1±5.92; 16.4 (8.67, 27.6) | 17.2±5.93; 16.53 (8.73, 27.7) | 16.6±5.84; 15.8 (8.29, 27.21) | – | |

| Average ultrasonic testicular volume (mL)¶ | 17.6±5.09; 17.2 (10.1, 26.4) | 17.6±5.12; 17.3 (10.2, 26.4) | 17.4±4.98; 17.1 (10.0, 26.5) | – | |

| Prostate volume (mL)ǁ | 15.6±4.60; 15.2 (9.52, 23.8) | 15.7±4.65; 15.2 (9.52, 23.8) | 15.3±4.41; 15.2 (8.86, 22.9) | – | |

| Abstinence period (days) | – | 3.62±2.91; 3.00 (0.00, 10.0) | 3.69±2.86; 3.00 (0.00, 8.00) | 4.64±2.88; 4.00 (0.00, 10.0) | 3.78±2.92; 3.00 (0.00, 10.0) |

| Semen volume (mL) | – | 3.00±1.36; 2.80 (1.10, 5.50) | 3.08±1.34; 2.90 (1.20, 5.60)** | 3.34±1.35; 3.20 (1.40, 5.80)** | 3.06±1.36; 2.90 (1.10, 5.60) |

| Concentration (×106/mL) | – | 81.3±46.1; 79.0 (13.0, 162) | 76.4±48.6; 70.0 (9.00, 161)** | 82.4±47.0; 81.0 (12.0, 167)** | 80.7±46.7; 78.0 (12.0, 162) |

| Total motility (%) | – | 49.0±14.7; 51.0 (22.0, 71.0) | 46.3±15.5; 48.0 (20.0, 69.0)** | 47.5±15.0; 49.0 (21.0, 70.0)** | 48.4±14.9; 50.0 (21.0, 70.0) |

| VSL (μm/s) | – | 42.7±9.26; 42.7 (27.2, 58.5) | 41.2±9.53; 41.1 (25.5, 57.5) | 41.4±9.45; 41.2 (26.3, 57.8) | 42.3±9.35; 42.3 (26.7, 58.5) |

| TMSC (×106) | – | 130.7±112.7; 101.8 (7.31, 348) | 122.8±116.2; 88.7 (5.49, 354)** | 141.6±117.1; 111.0 (9.18, 369)** | 131.1±114.0; 101.4 (6.98, 353) |

Data are presented as mean ± SD; median (5th percentile, 95th percentile). †, data about LH was available in n=9,405 for the total sample; n=7,177 for the one-time sampling group; n=1,688 for the two-time sampling group. ‡, data about FSH was available in n=8,083 for the total sample; n=6,530 for the one-time sampling group; n=1,553 for the two-time sampling group. §, data about total testosterone was available in n=9,435 for the total sample; n=7,742 for the one-time sampling group; n=1,693 for the two-time sampling group. ¶, data about average ultrasonic testicular volume was available in n=8,766 for the total sample; n=7,116 for the one-time sampling group; n=1,650 for the two-time sampling group. ǁ, data about prostate volume was available in n=5,332 for the total sample; n=4,226 for the one-time sampling group; n=1,106 for the two-time sampling group. **, P<0.01 using the Wilcoxon signed rank test to compare the longer vs. shorter abstinence time within a group. EAT1, sample with shorter ejaculatory abstinence; EAT2, sample with longer ejaculatory abstinence; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; SD, standard deviation; TMSC, total motile sperm count; VSL, straight-line velocity.

When analyzing the total 11,297 semen profiles of all participants, Kruskal-Wallis tests showed significant differences in all semen parameters between groups classified by abstinence periods with P<0.001 (Table 2, with the result of Dunn posthoc tests shown in Tables S1-S5 and further visualized in Figures S1-S5). Semen volume, sperm concentration, and TMSC increased and peaked after 4, 5, and 5 abstinence days, respectively. On the other hand, VSL and total motility of sperm varied and did not follow apparent trends. When testing for the trend, there were increases in semen volume (mL) (P<0.001), sperm concentration (×106/mL) (P<0.001), total motility (%) (P<0.001), VSL (µm/s) (P=0.03), and TMSC (×106) (P<0.001) following the extension of abstinence time. Further exploring data by using age-adjusted linear regressions, results indicated only positive relationships between the abstinence time and semen volume (β=0.14, P<0.001), sperm concentration (β=3.76, P<0.001), total motility (β=0.16, P=0.001), TMSC (β=11.7, P<0.001), but not in the case of VSL (β=0.05, P=0.11).

Table 2

| Semen parameters | Abstinence time (n=11,297) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 day (n=1,343) | 1 day (n=967) | 2 days (n=1,596) | 3 days (n=2,372) | 4 days (n=1,469) | 5 days (n=1,016) | 6 days (n=322) | 7 days (n=1,517) | >7 days (n=695) | |

| Semen volume (mL) | 2.17±1.05; 2.00 (0.80, 4.10) | 2.54±1.15; 2.30 (1.00, 4.70) | 2.76±1.21; 2.60 (1.10, 5.10) | 3.06±1.24; 2.90 (1.30, 5.40) | 3.32±1.32; 3.20 (1.40, 5.80)† | 3.52±1.36; 3.30 (1.50, 6.00)‡ | 3.58±1.37; 3.40 (1.50, 6.10)†,‡,§ | 3.50±1.40; 3.40 (1.40, 6.00)†,‡,§ | 3.81±1.51; 3.70 (1.50, 6.60)§ |

| Concentration (×106/mL) | 61.9±44.0; 52.0 (8.00, 146) | 69.2±44.0; 62.0 (7.00, 145)† | 72.9±43.8; 70.0 (11.0, 149)† | 79.0±45.0; 76.0 (12.4, 158)‡ | 82.8±46.3; 82.0 (15.0, 163)‡ | 89.6±45.7; 90.0 (16.0, 170)§ | 91.3±44.8; 93.0 (22.0, 167)§,¶ | 95.9±46.8; 97.0 (19.0, 175)¶,ǁ | 101.9±47.5; 108.0 (19.0, 175)ǁ |

| Total motility (%) | 45.1±15.2; 46.0 (19.0, 69.0)† | 47.7±15.2; 49.0 (19.0, 70.0)‡ | 48.4±15.1; 50.0 (21.0, 71.0)‡,§ | 49.1±14.9; 51.0 (22.0, 71.0)‡,§,¶ | 49.9±14.6; 52.0 (23.0, 71.0)§,¶ | 49.2±15.1; 51.0 (22.0, 70.0)‡,§,¶ | 50.0±15.3; 51.0 (22.0, 71.0)‡,§,¶ | 48.9±14.3; 50.0 (22.0, 70.0)‡,§,¶,ǁ | 46.9±14.8; 48.0 (19.0, 68.0)†,‡,§,ǁ |

| VSL (μm/s) | 41.3±9.38; 41.5 (26.3, 57.2)† | 42.5±9.71; 42.4 (25.6, 58.7)†,‡ | 42.1±9.41; 42.0 (26.9, 58.5)†,‡ | 42.4±9.30; 42.5 (26.8, 58.5)‡ | 42.6±9.44; 42.8 (26.7, 58.8)‡ | 42.8±9.33; 42.8 (27.3, 58.5)‡ | 43.2±8.99; 43.2 (27.3, 57.8)‡ | 42.5±9.21; 42.4 (27.4, 58.2)‡ | 41.8±9.05; 41.5 (26.5, 57.3)†,‡ |

| TMSC (×106) | 69.8±78.1; 44.6 (3.04, 232) | 92.1±89.0; 66.8 (4.18, 246) | 104.3±88.9; 82.9 (5.92, 276) | 126.1±103.5; 101.6 (8.37, 323) | 145.2±114.6; 122.0 (10.6, 358) | 163.6±122.7; 140.1 (12.0, 389)† | 170.7±127.5; 140.4 (17.7, 410)†,‡ | 173.7±127.3; 149.5 (14.6, 410)†,‡ | 193.9±139.5; 177.7 (14.0, 455)‡ |

Data are presented as mean ± SD; median (5th percentile, 95th percentile). Differences in semen parameters regarding abstinence time were tested using Kruskal-Wallis tests with P<0.001 in all comparisons. †, ‡, §, ¶, ǁ, paired comparisons were investigated using the post hoc Dunn tests with the Bonferroni adjustment for which groups shared the same superscript (i.e., †, ‡, §, ¶, ǁ) were not significantly different P>0.05. SD, standard deviation; TMSC, total motile sperm count; VSL, straight-line velocity.

Considering participants who had done semen analysis twice, significant differences in all semen parameters were found between the sample with longer (EAT2) vs. shorter abstinence times (EAT1), except VSL (P=0.29) (Table 1). However, these results were inconsistent in subgroup analyses based on two-time abstinence deviations (∆EAT2-T1).

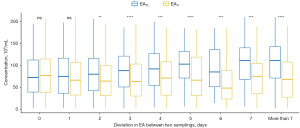

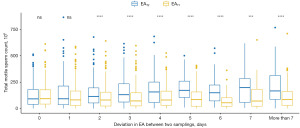

Figures described results from paired tests which showed alteration in semen volume (mL) (Figure 1), sperm concentration (×106/mL) (Figure 2), total motility (%) (Figure 3), VSL of sperm (µm/s) (Figure 4), and TMSC (×106) (Figure 5) comparing between the longer (EAT2) and shorter abstinence (EAT1). In cases where abstinence periods of two semen analyses were identical (∆EAT2-T1 =0), there were no significant differences in semen volume, sperm concentration, total motility, VSL, and TMSC. Only semen volume significantly increased after a 1-day extending in abstinence period (∆EAT2-T1 ≥1). A 2-day increase in the abstinence period (∆EAT2-T1 ≥2) was enough to create statistical changes in sperm concentration and TMSC. Moreover, these variations between the two semen analyses seemed to follow upward directions according to lengthening the two-time abstinence deviation (∆EAT2-T1) with P<0.001 when using non-parametric trend and Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Significant increases in total motility were only observed in cases of 4- and 5-day extending the abstinence period (∆EAT2-T1 =4 or 5) (Figure 3). On the other hand, VSL seemed to be consistent regardless of changes in abstinence periods between two samplings. Indeed, no differences in variations of VSL or total motility (between longer and shorter abstinence) were found when comparing groups with distinct two-time abstinence deviations (∆EAT2-T1).

Variations in semen parameters between the two episodes were significantly influenced by the abstinence time in both univariate and multivariate linear regressions (Tables 3,4). Increasing the abstinence of the sampling with a shorter time (EAT1) negatively reduced the two-time variations in ∆semen volume, ∆sperm concentration, ∆total motility, ∆VSL, and ∆TMSC. On the other hand, changes in semen volume, sperm concentration, and TMSC between the two samplings were larger when extending the two-time abstinence deviation (∆EAT2-T1). It should be noted that the abstinence period contributed to changes in total motility and VSL with small R-squared at levels of 0.0125 and 0.0077, respectively. Moreover, ∆TMSC was also influenced by ejaculation frequency (β=4.62, P=0.02) and serum FSH concentration (β=−2.03, P=0.03).

Table 3

| Independent variables | ∆Semen volume (mL) | ∆Concentration (×106/mL) | ∆Total motility (%) | ∆VSL (μm/s) | ∆TMSC (×106) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.00)* | −0.04 (−0.39, 0.31) | 0.00 (−0.12, 0.12) | −0.06 (−0.13, 0.01) | −0.29 (−1.19, 0.61) |

| Ejaculation frequency (times per week)† | 0.05 (0.01, 0.09)** | 1.20 (−0.29, 2.68) | 0.37 (−0.12, 0.86) | 0.29 (−0.02, 0.60) | 4.19 (0.40, 7.99)* |

| LH (IU/L)‡ | 0.00 (−0.03, 0.02) | −0.72 (−1.60, 0.17) | 0.02 (−0.28, 0.31) | −0.02 (−0.20, 0.17) | −1.30 (−3.58, 0.97) |

| FSH (IU/L)§ | −0.02 (−0.04, 0.00) | −0.51 (−1.23, 0.21) | 0.04 (−0.20, 0.27) | 0.03 (−0.12, 0.18) | −2.19 (−4.05, −0.32)* |

| Total testosterone (nmol/L)¶ | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | −0.09 (−0.46, 0.29) | 0.00 (−0.12, 0.13) | −0.04 (−0.12, 0.04) | −0.05 (−1.00, 0.90) |

| Average ultrasonic testicular volume (mL)ǁ | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 0.39 (−0.05, 0.83) | −0.13 (−0.27, 0.02) | −0.06 (−0.15, 0.03) | 1.12 (−0.01, 2.25) |

| Prostate volume (mL)# | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | −0.22 (−0.84, 0.40) | 0.06 (−0.14, 0.26) | 0.06 (−0.07, 0.18) | −0.67 (−2.29, 0.95) |

| EAT1 (days) | −0.13 (−0.16, −0.10)** | −2.70 (−3.73, −1.67)** | −0.79 (−1.13, −0.44)** | −0.35 (−0.56, −0.13)** | −8.67 (−11.3, −6.05)** |

| ∆EAT2-T1 (days) | 0.12 (0.10, 0.14)** | 3.79 (2.97, 4.62)** | 0.00 (−0.28, 0.28) | 0.23 (0.05, 0.40)* | 10.2 (8.14, 12.3)** |

Data are presented as β (95% CI). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01. †, data about ejaculation frequency was available in n=1,394. ‡, data about LH was available in n=1,688. §, data about FSH was available in n=1,553. ¶, data about total testosterone was available in n=1,693. ǁ, data about average ultrasonic testicular volume was available in n=1,650. #, data about prostate volume was available in n=1,106. CI, confidence interval; EAT1, sample with shorter ejaculatory abstinence; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; TMSC, total motile sperm count; VSL, straight-line velocity; ∆EAT2-T1, deviation in ejaculatory abstinence of two samples.

Table 4

| Independent variables | ∆Semen volume (mL), n=1,491 | ∆Concentration (×106/mL), n=1,702 | ∆Total motility (%), n=1,702 | ∆VSL (μm/s), n=1,702 | ∆TMSC (×106), n=1,394 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.00) | – | – | – | – |

| Ejaculation frequency (times per week) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.09)* | – | – | – | 4.62 (0.70, 8.55)* |

| FSH (IU/L) | – | – | – | – | −2.03 (−3.91, −0.15)* |

| EAT1 (days) | −0.09 (−0.12, −0.06)** | −1.68 (−2.72, −0.63)** | −0.83 (−1.19, −0.48)** | −0.30 (−0.52, −0.07)** | −3.28 (−6.31, −0.25)* |

| ∆EAT2-T1 (days) | 0.11 (0.09, 0.14)** | 3.47 (2.62, 4.31)** | −0.16 (−0.45, 0.12) | 0.17 (−0.01, 0.35) | 9.80 (7.41, 12.2)** |

| R2 | 0.1060 | 0.0514 | 0.0125 | 0.0077 | 0.0632 |

Data are presented as β (95% CI). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01. CI, confidence interval; EAT1, sample with shorter ejaculatory abstinence; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; TMSC, total motile sperm count; VSL, straight-line velocity; ∆EAT2-T1, deviation in ejaculatory abstinence of two samples.

Discussion

Results from the presented study reemphasized the crucial role of EA on variations of semen parameters. This study distinguishes itself from prior research by incorporating three key aspects: it evaluates the impact of EA through both between-individual and within-individual approaches, allows for variable EA at different time points in the within-individual approach, and concurrently examines the influence of EA on various sperm parameters. The quantity of sperm increased with extending abstinence day in both between- and within-individual analyses. Sperm concentration and TMSC were not significantly different if the two-time abstinence deviation was no longer than 2 days. Interestingly, two-sampling variations in these above indications tended to decrease when increasing EA and reducing the deviation in EA between two times. On the other hand, VSL did not seem to be affected by EA.

Impacts of EA on semen parameters using between-individual approach

When focusing on between-individual variations, previous studies have consistently shown that semen volume and sperm concentration significantly increase following extending EA (4,7,21-27). However, the optimal EA for the peak value of semen parameters remains controversial when using solely between-group comparison analyses (25,27-30). Indeed, semen volume and sperm concentration were proven to be positively correlated with lengthening EA, which was also found in the presented study (10,22,25). Moreover, multivariate analyses with comparatively large sample sizes highlighted the independent roles of extending EA in increasing semen volume and sperm concentration (7,23,31). Since these upward trends did exist, recommendations on the ideal EA for maximizing sperm count could not possibly be made.

On the other hand, the relationship between EA and total motility remains questionable. While some previous studies did not show a statistically significant relationship (7,10,21,24,28,32), findings from others indicated a negative correlation between these two (22,23,27,29-31). A gradual reduction was observed in means total motility of groups with longer EA (29,30). Analyzing 6,022 semen samples, Levitas et al. found a negative influence of EA on total motility (β=−0.085, P<0.01) regardless of age (31). Keihani et al. also showed the same result in both oligozoospermic (β=−3.19, P<0.01) and normozoospermic (β=−1.9, P<0.01) men when increasing in the abstinence category (≤2, >2 and ≤5, >5 and ≤7, >7 days) (23). Indeed, these modest changes in total motility following one more day of abstinence do not reflect any clinical significance. Notwithstanding the same approach, presented data on 11,297 semen analyses indicated a significantly positive but comparatively weak correlation between EA and total motility (β=0.16, P<0.001). It should be noted that critical intra-individual factors could affect sperm motility rather than EA by itself (24,33-35); thus, between-subject analyses might not be sufficient to control these confounders.

In addition, EA also influences the TMSC (7,23,26,27,29,36). The presented study showed an increase in TMSC with extending EA, which was consistent with others. Theoretically, sperm are continuously stored in and take an average of 12 days to transit throughout the whole epididymis (37). At the end of its journey, sperm can achieve hyperactivation and capacitation (37). Regardless of massive ejaculation frequency, the transition time of sperm in the epididymis is not affected remarkably (37). Sperm reserve is mainly reduced in the cauda but not in the caput and corpus segments of the epididymis when the EA is shortened (37). Therefore, the longer the EA is, the more sperm is stored. Since the EA largely influenced sperm concentration and semen volume rather than total motility, the increase in TMSC is inevitable. Moreover, with an increase in seminal and prostate fluids accumulated during EA, the components of the fluid, especially metal traces and protective factors, also changed (38,39). The EA positively correlates with seminal zinc and magnesium, which are essential in sperm function after expelling out of the male body (38). Since these metals ensure the integrity of genetic material and are involved in ATP metabolism, providing energy for sperm motility (38,40), their increased presence in the semen sample may raise the number of motile sperm.

Impacts of EA on semen parameters using within-individual approach

To minimize intra-individual covariates, the present study also considers the effect of EA on semen parameters using variation analyses in one subject. In accordance with others (8,11-16,41,42), findings from our study consistently show that the longer the EA is, the higher the semen volume, sperm concentration, and TMSC are. On the other hand, changes in total motility are mostly non-significant when considering the two-time EA deviation that is different from between-individual analyses. Indeed, the relationship between total motility and EA, according to within-individual analyses, is still controversial. While some studies indicated no significant change (12,13,41,42), others showed a statistical increase when shortening the EA (14,15). However, the number of observations in this type of study is relatively small, leading to difficulty in providing clear conclusions based on their results.

For most of the studies using the within-individual approach, the EA of each time used to be fixed, thus limiting the ability to fully detect the effect of extending the abstinence period on semen parameters. In a study fixing the first sampling EA at 3–4 days and 1 day for subsequent times of six men, only semen volume and total sperm count increased with extending EA, but not in cases of sperm concentration (12). Another study showed that a 3-day EA deviation between two samplings (1 vs. 4 days EA) of 40 men resulted in significant increases in semen volume and sperm concentration (13). Analyzing the semen after 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 abstinence days of 10 men, Blackwell and Zaneveld found that semen volume and sperm concentration significantly increased only when EA deviations in the two samplings were 3-day more and 4-day more (41). De Jonge et al. indicated the same results but with statistical significance after at least a 4-day difference in EA between two samplings (1 vs. 5 days EA) (42). Consistently, other studies fixing the two-time EA deviation within 3–4 days also justified the above findings (14-16). With a sufficiently large number of observations and the full range of two-time EA deviation, the presented study suggested that sperm concentration and TMSC were relatively stable if the difference in EA between two samplings did not exceed 1 day. Moreover, we found that the variation between the two semen analyses decreased when shortening EA and applying the same EA each time. It has not been reported in previous studies. This fact needs to be considered when replicating the semen analysis is required.

Impact of EA on VSL

Differentiating from other parameters, VSL has the smallest degree of variation in both within- and between-individual analyses (10). The fluctuation in VSL between EA groups has been investigated in previous studies but without apparent negative trends (3,11,36). However, when testing EA as an independent variable in multivariate analysis, Pokhrel et al. could not confirm its relationship with VSL (24). Findings from our study also showed that EA did not correlate with VSL, especially in the within-individual approach that allowed partially controlling other covariates. Since the number of studies focusing on VSL was scarce, further studies should be conducted.

Strengths and limitations

The presented study uses one of the largest sample sizes analyzed with the support of CASA, reducing the measurement bias and making results more reliable. Focusing on men who have two semen analyses within 1 month is also an effective strategy to reveal the independent influence of EA. It should be noted that while semen analysis was taken twice, results from the second sampling might be affected by lifestyle changes or increased familiarity with sample collection, thus slightly influencing our findings. However, since we retrieved data from the database, some parameters that might be related to EA could not be thoroughly investigated. Even though this study restricted semen analysis to men with less than 14 days of abstinence, recall biases could naturally occur. Another limitation of the study is that the data were collected retrospectively, so some information about blood tests and testicular ultrasounds was not adequately stored in the system, leading to missing values. For the purpose of screening for male fertility problems, only a basic examination of semen samples was indicated; thus, we can not investigate the impact of EA on other sperm functions revealed by extended and advanced examinations, and further studies are required.

Conclusions

This study emphasizes the positive impact of EA on sperm quantity while casting doubt on similar effects concerning the total proportion of motility and VSL based on both within- and between-individual analyses. Therefore, to ensure that semen analyses are comparable, it is important to maintain consistent abstinence periods, ideally keeping them identical or differing by no more than 1 day from the first sample.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-553/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-553/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-553/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-553/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by Hanoi Medical University ethics committee (HMUIRB#1829). Due to the study’s retrospective and cross-sectional design, individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. 6th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

- Michels KA, Kim K, Yeung EH, et al. Adjusting for abstinence time in semen analyses: some considerations. Andrology 2017;5:191-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ayad BM, Horst GV, Plessis SSD. Revisiting The Relationship between The Ejaculatory Abstinence Period and Semen Characteristics. Int J Fertil Steril 2018;11:238-46. [PubMed]

- Hanson BM, Aston KI, Jenkins TG, et al. The impact of ejaculatory abstinence on semen analysis parameters: a systematic review. J Assist Reprod Genet 2018;35:213-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Degirmenci Y, Demirdag E, Guler I, et al. Impact of the sexual abstinence period on the production of seminal reactive oxygen species in patients undergoing intrauterine insemination: A randomized trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2020;46:1133-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Setti AS, Braga DPAF, Iaconelli A Junior, et al. Increasing paternal age and ejaculatory abstinence length negatively influence the intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes from egg-sharing donation cycles. Andrology 2020;8:594-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borges E Jr, Braga DPAF, Zanetti BF, et al. Revisiting the impact of ejaculatory abstinence on semen quality and intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes. Andrology 2019;7:213-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Martín P, Sánchez-Martín F, González-Martínez M, et al. Increased pregnancy after reduced male abstinence. Syst Biol Reprod Med 2013;59:256-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. 5th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Keel BA. Within- and between-subject variation in semen parameters in infertile men and normal semen donors. Fertil Steril 2006;85:128-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alipour H, Van Der Horst G, Christiansen OB, et al. Improved sperm kinematics in semen samples collected after 2 h versus 4-7 days of ejaculation abstinence. Hum Reprod 2017;32:1364-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mayorga-Torres BJ, Camargo M, Agarwal A, et al. Influence of ejaculation frequency on seminal parameters. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2015;13:47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marshburn PB, Giddings A, Causby S, et al. Influence of ejaculatory abstinence on seminal total antioxidant capacity and sperm membrane lipid peroxidation. Fertil Steril 2014;102:705-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goss D, Ayad B, van der Horst G, et al. Improved sperm motility after 4 h of ejaculatory abstinence: role of accessory sex gland secretions. Reprod Fertil Dev 2019;31:1009-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okada FK, Andretta RR, Spaine DM. One day is better than four days of ejaculatory abstinence for sperm function. Reprod Fertil 2020;1:1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dahan MH, Mills G, Khoudja R, et al. Three hour abstinence as a treatment for high sperm DNA fragmentation: a prospective cohort study. J Assist Reprod Genet 2021;38:227-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Francavilla F, Barbonetti A, Necozione S, et al. Within-subject variation of seminal parameters in men with infertile marriages. Int J Androl 2007;30:174-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal A, Gupta S, Du Plessis S, et al. Abstinence Time and Its Impact on Basic and Advanced Semen Parameters. Urology 2016;94:102-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nguyen Hoai B, Hoang L, Tran D, et al. Ultrasonic testicular size of 24,440 adult Vietnamese men and the correlation with age and hormonal profiles. Andrologia 2022;54:e14333. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Handelsman DJ, Sivananathan T, Andres L, et al. Randomised controlled trial of whether erotic material is required for semen collection: impact of informed consent on outcome. Andrology 2013;1:943-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zou Z, Hu H, Song M, et al. Semen quality analysis of military personnel from six geographical areas of the People's Republic of China. Fertil Steril 2011;95:2018-23, 2023.e1-3.

- Comar VA, Petersen CG, Mauri AL, et al. Influence of the abstinence period on human sperm quality: analysis of 2,458 semen samples. JBRA Assist Reprod 2017;21:306-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keihani S, Craig JR, Zhang C, et al. Impacts of Abstinence Time on Semen Parameters in a Large Population-based Cohort of Subfertile Men. Urology 2017;108:90-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pokhrel G, Yihao S, Wangcheng W, et al. The impact of sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, work exposure and medical history on semen parameters in young Chinese men: A cross-sectional study. Andrologia 2019;51:e13324. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen GX, Li HY, Lin YH, et al. The effect of age and abstinence time on semen quality: a retrospective study. Asian J Androl 2022;24:73-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kabukçu C, Çil N, Çabuş Ü, et al. Effect of ejaculatory abstinence period on sperm DNA fragmentation and pregnancy outcome of intrauterine insemination cycles: A prospective randomized study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2021;303:269-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meitei HY, Uppangala S, Lakshmi RV, et al. Sperm characteristics in normal and abnormal ejaculates are differently influenced by the length of ejaculatory abstinence. Andrology 2022;10:1351-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mortimer D, Templeton AA, Lenton EA, et al. Influence of abstinence and ejaculation-to-analysis delay on semen analysis parameters of suspected infertile men. Arch Androl 1982;8:251-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levitas E, Lunenfeld E, Weiss N, et al. Relationship between the duration of sexual abstinence and semen quality: analysis of 9,489 semen samples. Fertil Steril 2005;83:1680-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sobreiro BP, Lucon AM, Pasqualotto FF, et al. Semen analysis in fertile patients undergoing vasectomy: reference values and variations according to age, length of sexual abstinence, seasonality, smoking habits and caffeine intake. Sao Paulo Med J 2005;123:161-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levitas E, Lunenfeld E, Weisz N, et al. Relationship between age and semen parameters in men with normal sperm concentration: analysis of 6022 semen samples. Andrologia 2007;39:45-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao J, Gao ES, Yang Q, et al. Semen quality in a residential, geographic and age representative sample of healthy Chinese men. Hum Reprod 2007;22:477-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Diemer T, Huwe P, Ludwig M, et al. Urogenital infection and sperm motility. Andrologia 2003;35:283-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baumber J, Ball BA, Gravance CG, et al. The effect of reactive oxygen species on equine sperm motility, viability, acrosomal integrity, mitochondrial membrane potential, and membrane lipid peroxidation. J Androl 2000;21:895-902. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luconi M, Forti G, Baldi E. Pathophysiology of sperm motility. Front Biosci 2006;11:1433-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elzanaty S, Malm J, Giwercman A. Duration of sexual abstinence: epididymal and accessory sex gland secretions and their relationship to sperm motility. Hum Reprod 2005;20:221-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robaire B, Hinton BT, Orgebin-Crist MC. CHAPTER 22 - The Epididymis. In: Neill JD. editor. Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction (Third Edition). St. Louis: Academic Press; 2006:1071-148.

- Rodríguez-Díaz R, Blanes-Zamora R, Vaca-Sánchez R, et al. Influence of Seminal Metals on Assisted Reproduction Outcome. Biol Trace Elem Res 2023;201:1120-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ndovi TT, Parsons T, Choi L, et al. A new method to estimate quantitatively seminal vesicle and prostate gland contributions to ejaculate. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:404-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Björndahl L, Kvist U. Sequence of ejaculation affects the spermatozoon as a carrier and its message. Reprod Biomed Online 2003;7:440-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blackwell JM, Zaneveld LJ. Effect of abstinence on sperm acrosin, hypoosmotic swelling, and other semen variables. Fertil Steril 1992;58:798-802. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Jonge C, LaFromboise M, Bosmans E, et al. Influence of the abstinence period on human sperm quality. Fertil Steril 2004;82:57-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]