Neourethra reconstruction using an anterior bladder wall flap for the treatment of complex urethral obliteration and absence

Highlight box

Key findings

• This manuscript addresses the rare and challenging cases of complex, lengthy proximal urethral obliterations in both male and female patients—a condition that poses significant surgical difficulties.

What is known and what is new?

• The lack of standardized techniques for urethral reconstruction further complicates treatment.

• This study demonstrates the effectiveness of using an anterior bladder wall flap for complex proximal urethral reconstruction, a technique with limited documentation in the literature. In this case series, we successfully reconstructed the obliteration lengths ranging from 5 to 15 cm in males and 3 to 5 cm in females, achieving satisfactory long-term follow-up outcomes.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Reconstruction of the neourethra using an anterior bladder wall flap presents a promising approach for treating congenital female proximal urethral absence and traumatic obliteration. While this technique offers favorable outcomes, a high risk of complications persists. Individualized treatment based on patient-specific anatomy is essential. As a retrospective study, due to its limited sample size, there are indeed many biases. With the increase of sample size, we hope to reduce such errors through further follow-up.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, advances in urethral surgery have improved treatment for pelvic fracture-related urethral strictures (1-6). However, no consensus exists on optimal management for complex proximal strictures, particularly in patients with severe trauma or failed prior surgeries. In these cases, with extensive urethral defects and obliteration, end-to-end anastomosis or traditional flaps are often insufficient.

Complete urethral absence or strictures in females are rare, often caused by urethrectomy for cancer, pelvic trauma, or congenital bladder exstrophy. Conventional methods, such as labial flap or oral mucosa, restore urethral patency but leave patients incontinent, limiting therapeutic effectiveness.

The objective of this study was to report on the treatment outcomes of 27 patients with total urethral stricture or urethral absence who underwent urethral reconstruction using an anterior bladder wall flap. This treatment of urethral reconstruction can not only achieve anatomical restoration, but also restore functional urinary continence. We believe this surgical method is ideal for the treatment of long proximal urethral obliteration and absence. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-443/rc).

Methods

Patient selection

A total of 27 patients with a complex urethral stricture underwent stage 1 urethral reconstruction from January 1990 to December 2023. Anterior rather than posterior bladder wall flap reconstruction was performed in 11 male patients and 16 female patients with complete absence of the urethra or stricture.

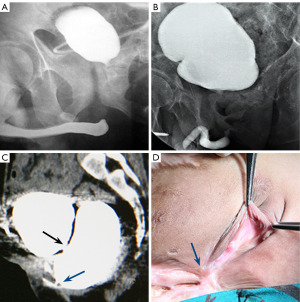

Etiologies included trauma, urethral cancer, vulvar cancer, and congenital bladder exstrophy with an absence of urethra. Preoperative evaluation included clinical history-taking, physical examination, routine preoperative examination, urine culture, retrograde and voiding cystourethrography, and cystoscopy. Urethrography and cystoscopy revealed a normal bladder capacity (>200 mL), normal shape and no obvious inflammation. However, a closed bladder neck and long urethral stricture were observed in 25 patients (Figure 1A,1B). Two females with urethral and vulvar cancer, respectively, underwent total urethral resection and congenital urinary bladder exstrophy; vaginal agenesis and distal stenosis were noted in one female patient. Four female patients had severe scar tissue in the lower abdomen, vesicovaginal fistula, distal vaginal stenosis and atresia, and severe proximal expansion of the vagina (Figure 1C). Physical examination of the external genitalia revealed no urethral orifice or vaginal opening in two patients (Figure 1D). Tables 1,2 provide the patient characteristics.

Table 1

| No. | Age, years | Etiology | Failure of time | Stricture length, cm | Urethroplasty | Complication | Follow up (months) | Qmax (mL/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | Trauma | 2 | 15 | Bladder & skin flap | 350 | 19 | |

| 2 | 38 | Trauma | 1 | 7 | Bladder flap | Incontinence | 120 | 16.8 |

| 3 | 24 | Trauma | 2 | 6 | Bladder flap | Incontinence | 110 | 18.6 |

| 4 | 36 | Trauma | 1 | 6 | Bladder flap | 47 | 22.1 | |

| 5 | 25 | Trauma | 2 | 6 | Bladder flap | Dysuria | 38 | 0 |

| 6 | 9 | Trauma | 2 | 9 | Bladder flap | 36 | 26.7 | |

| 7 | 36 | Trauma | 2 | 6 | Bladder flap | 31 | 22 | |

| 8 | 63 | Trauma | 2 | 6 | Bladder flap | Dysuria | 24 | 16.4 |

| 9 | 4 | Trauma | 1 | 5 | Bladder flap | 16 | 13.2 | |

| 10 | 19 | Trauma | 1 | 6.5 | Bladder flap | 15 | 17 | |

| 11 | 54 | Trauma | 1 | 6 | Bladder flap | 13 | 24.6 |

Qmax, maximum flow rate..

Table 2

| No. | Age, years | Etiology | Failure of postoperative time | Stricture length, cm | Complication | Follow up (months) | Qmax (mL/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | Trauma | 1 | 4 | 108 | 23 | |

| 2 | 10 | Trauma | 1 | 4 | 84 | 17.8 | |

| 3 | 6 | Trauma | 0 | 3 | 80 | 18.2 | |

| 4 | 53 | Trauma | 1 | 4 | Incontinence | 72 | 25.1 |

| 5 | 54 | Trauma | 1 | 5 | Incontinence | 58 | 18.4 |

| 6 | 12 | Trauma | 1 | 3 | 56 | 19.6 | |

| 7 | 39 | Trauma | 1 | 5 | Incontinence | 53 | 24 |

| 8 | 4 | Trauma | 0 | 3.5 | 42 | 16.4 | |

| 9 | 5 | Trauma | 0 | 3 | 36 | 19 | |

| 10 | 36 | Trauma | 1 | 3 | Dysuria | 28 | 0 |

| 11 | 60 | Trauma | 0 | 3.5 | 16 | 34.6 | |

| 12 | 71 | UC | 0 | 3 | 28 | 13.6 | |

| 13 | 65 | UC | 0 | 4 | Dysuria | 25 | 0 |

| 14 | 73 | Trauma | 0 | 3 | 21 | 14.7 | |

| 15 | 70 | Trauma | 0 | 3 | Incontinence | 19 | 15.8 |

| 16 | 22 | CUBE | 0 | 4 | 20 | 23 |

CUBE, congenital urinary bladder exstrophy; Qmax, maximum flow rate.; UC, urethral cancer.

Surgical technique

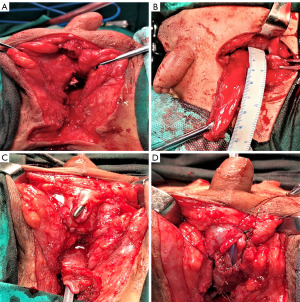

All patients passed a comprehensive preoperative assessment. Surgeries were performed by Dr. Xu and his team at Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, with patients positioned in lithotomy under general anesthesia. Surgery duration ranged from 125 to 190 minutes. First, through a perineal incision, the anterior urethra was dissected and the fibrotic prostatic urethra was resected to form an opening sufficient for the passage of a tubularized bladder wall flap through the lumen in 11 male patients (Figure 2A), and under the pubic bone to the genitals in 16 female patients. Second, a lower abdominal incision was made to create an anterior bladder wall flap (width, 2–2.5 cm; length, 4–10 cm) separated from the bladder neck to the later portion (Figure 2B). The flap was tubularized around a 12–14-Fr catheter in two layers, with 4-0 polyglactin sutures used to form a new urethra (Figure 2C). The suture was tightened to provide slight tension as the catheter was moved, and the catheter was then replaced with a smaller (10–12-Fr) catheter. The neourethra was pulled into the perineal incision and anastomosed end-to-end in 10 of the 11 male patients (Figure 2D). The remaining male patient had been injured in a traffic accident when he was 14 years old. Secondary infection resulted in urethral atresia 34 years prior. In this patient, a bladder wall flap approximately 2-cm wide and 9-cm long was used to form a new proximal urethra. The remaining part of the anterior urethra was reconstructed using a penile circular fasciocutaneous skin flap.

In 16 of our female patients, a tubular bladder flap was flipped through a tunnel below the pubic bone to the location of the original external urethral meatus (Figure 3A,3B). In one patient with congenital urinary bladder exstrophy, whose operation was performed using a transpubic approach, the distal part of the flap was sutured to the surrounding skin to form a new external urethral orifice (Figure 3C).

Four girls with severe vaginal stenosis or obliteration of the distal vagina underwent a supplementary procedure which was island vulvar-flap-enlarging vaginoplasty and reconstruction of the vaginal orifice using the proximal vaginal wall.

Postoperative management

All patients received intravenous antibiotics for 7 days, the catheters remained for 4 weeks. The patients received oral antibiotic prophylaxis until the catheter was removed. To maintain vaginal cleanliness of the female patients, the vagina was douched with disinfectant daily. The suprapubic catheter was left in place for 6 weeks postoperatively, and a voiding cystourethrogram was performed prior to a formal voiding trial. Voiding status was also assessed in patient interviews conducted during follow-up appointments, or by telephone interviews. If the patient complained of a subjectively weak stream and uroflowmetry showed an output rate <15 mL/s (age <60 years) or <10 mL/s (age ≥60 years), further investigations were conducted, including urethrography and urethrocystoscopy. Successful reconstruction was defined as normal voiding with the output flow >15 mL/s (age <60 years) or >10 mL/s (age ≥60 years) and without the need for postoperative procedures, such as dilatation.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as median (range) or mean standard deviation for continuous data and as number (%) for categorical data. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (25.0).

Ethical statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Informed consent was taken from all the patients or their legal guardians. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine [No. 2025-KY-019(K)].

Results

The mean age was 29.3 (range, 4–63) years in male patients and 37.1 (range, 4–73) years in female patients. The mean stricture length in male patients was 7.1 (range, 5–15) cm (Table 1) and 3.6 (range, 3–5) cm (Table 2) in 16 female patients with complete absence of the urethra or stricture. There were no serious perioperative complications and the catheter was removed at 4–6 weeks postoperatively in all patients. In Table 1, 11 patients were followed up for a mean of 72.7 (range, 13–350) months. The procedure was successful in 7 of 11 patients (63.6%). Urethrograms revealed a patent urethra with an adequate lumen (Figure 4A,4B). Dysuria occurred in two patients, in whom cystoscopy examination showed that irregular edema or prolapse of the new urethra mucosa in the bladder neck had caused obstruction (Figure 5). Both patients could easily void without incontinence after resection of the prolapsed mucosa; notably, one of these patients was followed for 350 months. In addition, stress urinary incontinence developed postoperatively in two patients.

Among three children, one boy (No. 6) whose urethral replacement involved a particularly long length of the bladder wall achieved good postoperative urination control (Table 1). The boy achieved a urinary peak flow of 26.7 mL/s and maximum urethral pressure of 89 cmH2O at 3 years (Figure 6A,6B). For one of the other boys (No. 9), the “urethral pressure map” indicated high pressure (similar to the sphincter muscle findings), as opposed to uniform pressure lines.

In Table 2, the surgery was successful in all 16 female patients and there were no serious perioperative complications. All 16 of these patients were followed up for 16–108 months (average =46.6 months), 10 patients had good urinary control and voiding (62.5%), 4 had stress urinary incontinence (25%), and 2 had urination difficulties (12.5%). Examination revealed mucosal prolapse at the neck of the bladder in one of the two patients and urethral meatal stenosis in the other one. Both of these patients underwent endoscopic resection of the prolapsed mucosa and meatoplasty using a vulvar flap. After these procedures, the patients were able to void easily. These patients with incontinence received the drug therapy and rehabilitation physiotherapy. Most of these patients have got the social continence or clinical continence. They use less than one pad every day.

Overall, 3 patients (11.1%) encountered Clavien-Dindo grade 1 complications during their in-hospital stay. Notably, there were local wound complications in these three patients and there were 6 patients with stress urinary incontinence (22.2%) classified as complications (Clavien-Dindo II), 4 instances (14.8%) classified as major complications requiring surgical intervention (Clavien-Dindo IIIb).

Discussion

Complex and severe cases of proximal urethral obliteration are rare and particularly challenging to treat surgically due to the need for both anatomical restoration and functional urinary continence. In patients with previous surgical failure, reconstruction is often complicated by the scarcity of healthy tissue and extensive scarring. Additionally, if the stricture resulted from traumatic pelvic fracture, the membranous urethral sphincter may be compromised, making postoperative continence mainly dependent on the prostatic striated inner sphincter. A standardized technique for proximal neourethra reconstruction is yet to be established; treatment plans must consider the stricture’s etiology, length, and the health of the anterior urethra.

Urethral disruption caused by pelvic fracture injuries is rarer in women compared with men; such cases usually involve severe injuries. Multi-trauma cases are particularly complicated; local medical expertise is often lacking and facilities tend to be very poor. Moreover, emergency surgery is often impractical; typically, suprapubic cystotomy is performed in emergencies, but delays can result in extensive scarring and associated complications, such as urinary fistula formation, distal vaginal stenosis, and urine outflow obstruction leading to proximal hydrocolpos (Figure 1C). In our series, four girls had an obstructive urinary fistula and vaginal distal stenosis and the exterior entrance of the vagina was not located in the external genitals (Figure 1D). Children with proximal vaginal hydrocolpos often present with severe abdominal pain and need to undergo temporary drainage in the hospital to relieve pressure.

The bladder wall flap has favorable vascularization, elasticity, and rapid healing properties, allowing its use in creating a neourethra with benefits in structure and function. A bladder of normal size and shape can be rebuilt within the urethra. Using a tubularized bladder wall flap as a substitute for the neourethra has many advantages and is ideal for the treatment of proximal urethral obliteration. Despite the advantages, using bladder wall flaps in urethral reconstruction remains uncommon due to technical challenges and potential suboptimal outcomes.

Only a few small case series have been reported in the literature (1,6-9). Tanagho et al. reported three cases in which the anterior bladder wall was used as a substitute for the urethra in females with congenital absence of the urethra. A transverse incision was made in the neck of the bladder, and a 2.5×2.5 cm2 wall flap was separated out and rolled into a tube. This tube was then moved forward to form a new urethra in the genital area (9).

Raney reported 16 cases in which the anterior bladder wall flap was used for reconstruction of the bladder neck and urethra, to restore urethral continuity and continence (6). However, we believe that the cases described by Raney were simpler than cases involving severe trauma; extensive localized scar tissue is often present in trauma patients and it is also difficult to separate tissue from the bladder neck to the anterior urethra.

The urethral sphincter is often compromised in patients with proximal urethral long-segment obliteration caused by traumatic pelvic fracture. The ability to achieve urinary continence after urethral reconstruction using the bladder wall depends mainly on this muscular tube.

According to LaPlace’s law, fluid flow resistance in a tube is inversely correlated with lumen radius and positively correlated with wall tension and tube length (10), suggesting that the neourethral pressure should approximate the native urethral pressure. In this study, the incidence of postoperative urethral complications was relatively high; dysuria and stress urinary incontinence were seen in four and six patients, respectively. Postoperative outcomes were generally better in children than adult male patients. The urethral pressure map showed similar high pressure of the sphincter muscle rather than uniform pressure lines in two boys. It is feasible that the bladder wall is softer in children; with age, the bladder neck and prostate development influence urine control.

Our modified approach to the Tanagho procedure utilizes a 4–10 cm bladder wall flap from the bladder neck to the top bladder wall, tubularized to form a neourethra. This method, with the posterior wall positioning of the flap, may reduce urethral fistula formation. In trauma cases, Tanagho’s technique may not be appropriate due to scarring and adherence to the bladder neck, making the simpler anterior wall flap method preferable. In addition, it is difficult to separate tissue adhering to the bladder neck; a simple bladder anterior wall flap operation is more convenient. The bladder wall tube, which is reversed to the genitals to form a new urethra, is slightly elevated in the region of the bladder neck, thus providing a similar suspension effect that enhances postoperative urinary control. Optimal outcomes require posterior bladder wall flap reconstruction, adequate flap thickness and lumen diameter, and sufficient urethral length to prevent stricture and maintain continence. However, patients with a preoperative bladder volume of less than 200 mL or significant bladder inflammation are not suitable candidates for this procedure.

Conclusions

Surgical management of complex proximal urethral obliteration or urethral absence remains challenging. Reconstruction of the neourethra using an anterior bladder wall flap presents a promising approach for treating congenital female proximal urethral absence and traumatic obliteration. While this technique offers favorable outcomes, a high risk of complications persists. Individualized treatment based on patient-specific anatomy is essential. As a retrospective study, due to its limited sample size, there are indeed many biases. With the increase of sample size, we hope to reduce such errors through further follow-up.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-443/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-443/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-443/prf

Funding: This study was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-24-443/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Xu YM. Total urethral reconstruction using bladder wall flap combine and penile circular fasciocutaneous skin flap in treatment of total urethral atresia. Chinese J Urol 1991;12:246.

- Mundy AR, Andrich DE. Entero-urethroplasty for the salvage of bulbo-membranous stricture disease or trauma. BJU Int 2010;105:1716-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gupta NP, Mishra S, Dogra PN, et al. Transpubic urethroplasty for complex posterior urethral strictures: a single center experience. Urol Int 2009;83:22-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu YM, Sa YL, Fu Q, et al. Transpubic access using pedicle tubularized labial urethroplasty for the treatment of female urethral strictures associated with urethrovaginal fistulas secondary to pelvic fracture. Eur Urol 2009;56:193-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu YM, Sa YL, Fu Q, et al. A rationale for procedure selection to repair female urethral stricture associated with urethrovaginal fistulas. J Urol 2013;189:176-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raney AM. Reconstruction of bladder neck and prostatic urethra. Clinical experience with bladder flap. Urology 1974;3:324-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed S. Construction of female neourethra using a flipped anterior bladder wall tube. J Pediatr Surg 1995;30:1728-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edgerton MT, Gillenwater JY, Kenney JG, et al. The bladder flap for urethral reconstruction in total phalloplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984;74:259-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tanagho EA. Anterior detrusor flap in urogenital sinus repair. BJU Int 2008;101:647-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lapides J. Structure and function of the internal vesical sphincter. J Urol 1958;80:341-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]