Waiting in line for a fusion prostate biopsy—what does a patient know, fear and expect

Highlight box

Key findings

• Significant knowledge gaps exist among men undergoing prostate biopsy (PB): 17.5% were unaware of their prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, and many lacked clarity on potential complications or post-biopsy treatment options.

• Over half of the participants were uncertain whether a biopsy could accelerate cancer development, and nearly two-thirds believed it would always detect cancer if present.

What is known and what is new?

• Informed consent is a cornerstone of patient-centered care; however, patients often report feeling underinformed prior to invasive procedures.

• This study provides specific evidence that patients’ understanding of PB indications, techniques, and risks remains limited, regardless of whether they are first-time or repeat-biopsy patients.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Enhancing patient education is paramount to improve decision-making and reduce misconceptions.

• Clinicians should implement standardized, easily understandable counseling protocols—potentially including written, visual, or online resources—to ensure patients grasp the rationale, possible outcomes, and follow-up steps for PB.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide, accounting for a significant proportion of cancer-related deaths among men (1). According to the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines, the PCa diagnostic pathway involves an initial clinical assessment, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (mpMRI), and targeted biopsy (2). There has been a substantial rise in the number of prostate biopsies (PB) performed globally, with an estimated 2 million procedures conducted each year (3). PB can be performed using either a transrectal or transperineal approach, each offering different advantages and risk profiles. The transperineal approach is particularly beneficial, as it lowers the risk of sepsis (4) and enhances the detection rate of PCa in the anterior region (5). Furthermore, the introduction of MRI-guided targeted biopsies has significantly improved the detection of clinically significant PCa (6).

Most complications of PB are minor and self-limiting; however, more serious complications include infections, significant bleeding, and urinary retention (3). PB findings can be benign, malignant, or non-diagnostic. Each of these results is associated with specific risks and requires a tailored follow-up approach (7,8). In the context of clinically localized PCa, treatment options include active surveillance, radical prostatectomy and external-beam radiotherapy. The ProtecT trial revealed no statistically significant differences in PCa-specific mortality among these therapeutic modalities, indicating comparable long-term outcomes (9). While much attention has been devoted to the technical aspects of medical procedures and the efficacy of diagnostic interventions, the patient’s subjective experience has received relatively scant exploration. Patient-centered medical care emphasizes actively involving patients in decisions regarding their health, which is a fundamental expectation (10,11). However, achieving meaningful patient involvement poses significant challenges, particularly concerning patients’ understanding of medical information and procedures. Patients frequently report feeling uninformed or confused about their medical conditions and treatment plans due to ineffective communication practices (12). The objective of this study was to evaluate the level of knowledge patients acquire during the informed consent process for PB, focusing on their understanding of the procedure’s indications, potential outcomes, and implications. We hypothesized that the informed consent process would provide individuals with prostate lesions sufficient understanding of the prostate biopsy’s indications, potential outcomes, implications, and their specific risk of developing cancer. To investigate this hypothesis, we conducted a pre-biopsy survey assessing the knowledge of patients undergoing various PB procedures. We present this article in accordance with the SURGE reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-58/rc).

Methods

Patients and clinicians

Between November 2023 and June 2024, adult males aged 40 years and above were recruited for this study at the Department of Urology, Medical University of Gdańsk. Participants were scheduled to undergo various types of prostate biopsies, including transrectal mapping biopsy, transrectal fusion biopsy, and transperineal fusion biopsy. Patients were referred by various urologists to our tertiary care center, and no standardized protocol for pre-biopsy counseling was in place. Prior to their PB procedures, patients were asked to complete a one-time survey in Polish (their native language). The survey collected demographic information, history of past biopsies, and family history of PCa. Completed surveys and signed consent forms were returned to the study personnel. Patients who did not wish to participate were instructed to return a blank survey. The study protocol and informed consent documents were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Gdańsk. We designed a 17-item questionnaire comprising single-choice questions (SCQs), multiple-choice questions (MCQs), and open-ended questions (OEQs), which is available in Appendix 1. A total of 177 men responded to the survey. The demographic features of the respondents are shown in Table 1. Educational levels were as follows: 56.5% (100/177) had completed secondary education, 31.6% (56/177) had attained higher education, and 11.9% (21/177) had primary education only. Additionally, 19.2% (34/177) of respondents reported having a family member with PCa. For 72% of the respondents (128/177), the biopsy was their first time undergoing this procedure. Regarding the biopsy techniques used, 67 respondents (37.9%) underwent standard systematic transrectal PB, 75 (42.4%) underwent fusion transrectal PB, and 35 (19.8%) underwent fusion transperineal PB. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Gdańsk (No. MU-GD/2023/11-177) and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants prior to enrollment.

Table 1

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.5 (48–89) |

| PSA (ng/mL) | 6.32 (0.28–37.15) |

| Biopsy type | |

| Systematic | 67/177 (37.9) |

| Transrectal fusion | 75/177 (42.4) |

| Transperineal fusion | 35/177 (19.8) |

| Education | |

| Primary | 21/177 (11.9) |

| Secondary | 100/177 (56.5) |

| Higher | 56/177 (31.6) |

| History of previous prostate biopsy | 49/177 (27.7) |

| History of cancer | 28/177 (15.8) |

| Family history of prostate cancer | 34/177 (19.2) |

| DRE performed | 149/172 (86.6) |

Data are presented as mean (range) or n (%). DRE, digital rectal exam; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics and survey responses were entered into an electronic database and summarised as mean values with their standard deviations (SDs) or as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) based on data distribution. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05 without adjustment for multiple comparisons, and all analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

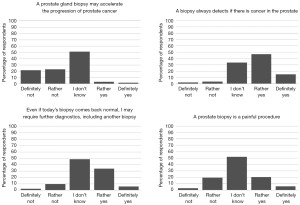

According to the survey results, 13.4% of the respondents reported that they had not undergone a digital rectal exam. Among those who did undergo the exam, approximately 40% did not receive any information regarding the findings. The remaining patients were informed either about the presence of a lesion or that nothing abnormal was found. Another notable finding was that 17.5% of the respondents indicated that they were unaware of their PSA levels. The Chi-squared test for independence revealed no statistically significant relationship between place of residence (size of the agglomeration) and knowledge of PSA levels [χ2(3, N=176) =4.814, P=0.19]. Similarly, there was no statistically significant association between educational attainment and knowledge of PSA levels. χ2(2, N=177) =5.407, P=0.07. Among these 177 men, 27.7% (49/177) had previously undergone at least one PB. Knowledge about potential complications and subsequent treatments did not significantly differ between first-time and repeat-biopsy participants. There is a statistically significant association (P<0.001) between patients’ awareness of the type of assigned biopsy and the actual type of biopsy they underwent. Patients undergoing standard systematic transrectal prostate biopsies were significantly less likely to be aware of the type of biopsy they were scheduled to receive. The results regarding knowledge of potential complications and the source of information are presented in Figure 1. The most commonly recognized complications following a PB were rectal bleeding (91/174, 52.3%), hematuria (79/174, 45.4%), and blood in semen (67/174, 38.5%). Additionally, 14 out of 174 patients (8%) were aware of sepsis as a potential complication. The survey revealed varying levels of awareness regarding treatment options: 53.7% knew about prostatectomy, 36% about radiotherapy, 30.3% about chemotherapy, 26.9% about active surveillance, and 14.3% about hormone therapy. Notably, 39.4% were unsure about available treatment options. The majority of respondents (67.1%, n=118) indicated that their primary source of information was their physician. The internet served as a secondary source of information for 36.6% (n=64) of participants. However, 12% (n=21) of respondents reported that they did not receive any information regarding the biopsy procedure. When asked to self-assess their understanding of the purpose and method of PB, 39.5% (n=68) of respondents rated their understanding as “good”, and 19.8% (n=34) as “very good”. Conversely, 36.6% (n=63) of participants felt that their understanding was “moderate”. A small percentage of respondents rated their understanding as “poor” (1.2%, n=2) or “very poor” (2.9%, n=5). Figure 2 shows the perceptions about PB. When asked whether PB can accelerate the development of PCa, over half of the respondents (50.9%) were uncertain, while 44.6% disagreed to some extent with the statement. Only a small fraction (4.6%) agreed. A significant majority (61.8%) believed that a biopsy always detects cancer if present. Only 5.1% disagreed with this statement, and 33.1% were uncertain. There were no statistically significant differences between the fusion biopsy group and the systematic biopsy group regarding perceptions of biopsy accelerating cancer progression (χ2=2.60, P=0.63), pain perception (χ2=3.42, P=0.49), diagnostic accuracy (χ2=0.77, P=0.94), or the need for further diagnostics (χ2=1.50, P=0.68).

Discussion

This study highlights significant gaps in patient awareness and understanding regarding PCa diagnostics, including DRE, PSA levels, and biopsy procedures. By surveying 177 men from diverse demographic and educational backgrounds, we gained valuable insights into these issues. Our survey revealed that 13.4% of respondents had not undergone a DRE, possibly reflecting the declining trend of its routine use in PCa diagnosis. For example, Naji et al. (13), in a meta-analysis of seven studies involving 9,241 patients, reported a pooled positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.41 and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 0.64 for DRE, leading to recommendations against its routine use. Among those who did undergo the exam, approximately 40% did not receive information about the findings. This communication gap may reduce the perceived value of DRE among patients, contradicting evidence that DRE can help detect more aggressive disease, such as ductal PCa with normal PSA. A significant finding was that 17.5% of respondents were unaware of their PSA levels, despite PSA testing’s critical role in early detection and management of PCa. Our analysis showed no significant relationship between knowledge of PSA levels and factors like place of residence or educational attainment. This widespread unawareness underscores the need for improved patient education from healthcare providers, regardless of demographic factors. We identified a substantial gap in patient awareness regarding the type of biopsy they were scheduled to receive. Patients were often unaware of the advantages and disadvantages of different biopsy procedures, pointing to potential issues in patient education and informed consent processes, especially for those receiving standard biopsy techniques. This lack of knowledge may affect their ability to make informed decisions about their care. Interestingly, there were no significant differences in knowledge about potential complications and treatment options between first-time biopsy patients and those undergoing repeat procedures. This suggests that prior biopsy experience does not necessarily enhance patient understanding, emphasizing the need for consistent education regardless of biopsy history. Possible reasons include inadequate information provided during previous procedures or difficulty retaining complex medical information. In our survey, 67.1% of respondents identified their physician as their primary information source, while 36.6% used the internet as a secondary source. Similarly, Morlando et al. (14) found that physicians were the most common information source on PCa screening (54.4%), followed by television/newspapers (35.8%) and family (23.4%). The reliance on secondary sources like the internet reflects the growing trend of patients seeking health information online (8). This trend underscores the importance of providing accurate and accessible information both in clinical settings and through reputable online platforms. When assessing patients’ perceptions about PB, we found notable misconceptions. Over half of the respondents (50.9%) were uncertain, and 44.6% disagreed to some extent when asked whether a PB can accelerate cancer development. This highlights the necessity for clinicians to address such concerns during pre-procedural counseling. Moreover, a significant majority (61.8%) believed that a biopsy always detects cancer if present. These observations align with earlier studies revealing that patients frequently hold misconceptions about medical procedures and associated risks (15). Additionally, there were no differences between the fusion and systematic biopsy groups regarding perceptions of biopsy-related cancer progression, pain, diagnostic accuracy, or the need for further diagnostics, indicating that patients share similar misconceptions and knowledge gaps regardless of the biopsy technique. This finding highlights critical areas where patient education and communication can be improved across all biopsy methods. Despite the high education level of the sample group, many patients had a poor understanding of their individual risk of malignancy, the potential outcomes of the biopsy, and subsequent follow-up procedures. Even for well-educated individuals, new diagnostic approaches can be challenging to comprehend. As imaging advances—exemplified by 68Ga-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT)—gain prominence, patient education becomes even more critical. While multiparametric mpMRI-targeted biopsy represents a major step forward, recent findings suggest that 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT-targeted biopsy may further improve detection of clinically significant PCa (16). However, these newer techniques can add complexity to patient decision-making, especially if baseline understanding of PCa diagnostics is already lacking. Additionally, patients were often unaware of the advantages and disadvantages of different biopsy procedures. These knowledge gaps, despite informed consent being obtained just prior to the biopsy, indicate a quality issue in the consent process. An inadequate consent process could impair patients’ ability to actively participate in decision-making regarding their biopsy. Factors contributing to this issue may include the complexity of medical terminology, time constraints during consultations, and variability in how information is communicated by different healthcare providers. This study has several limitations. The sample size and demographic characteristics may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader population. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce response bias, as participants might overestimate their understanding or provide socially desirable answers.

Recommendations for improving patient counseling

- Clarify indications: explain thoroughly why a biopsy is recommended and how imaging (e.g., mpMRI, PSMA PET/CT) can aid in lesion detection.

- Discuss biopsy choices: emphasize comparative benefits of transperineal vs. transrectal routes, including infection risks and detection of anterior prostate lesions.

- Communicate all findings: inform patients about the outcome of any DRE; highlight that a normal exam does not exclude clinically significant disease.

- Encourage questions: create an environment in which patients can comfortably inquire about potential complications, diagnostic accuracy, and follow-up care.

- Follow-up education: revisit important points after the biopsy, ensuring retention and comprehension, especially for patients needing repeat procedures.

Conclusions

Our findings underscore the significance of recognizing patients as active participants in their healthcare journey, illuminating the need for a patient-centered approach that transcends the procedural aspects of medical care. The knowledge gaps we have identified suggest an opportunity for improved patient education and communication, allowing individuals to navigate the uncertainty of a PB with a clearer understanding of the process and potential outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank nurse Joanna Stępień and nurse Monika Gulbińska (Department of Urology, Gdańsk Medical University) for their assistance during the clinical examinations of participants, including prostate biopsy.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SURGE reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-58/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-58/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-58/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-58/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Gdańsk (No. MU-GD/2023/11-177) and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants prior to enrollment.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:229-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer-2024 Update. Part I: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur Urol 2024;86:148-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borghesi M, Ahmed H, Nam R, et al. Complications After Systematic, Random, and Image-guided Prostate Biopsy. Eur Urol 2017;71:353-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pepe P, Pennisi M. Morbidity following transperineal prostate biopsy: Our experience in 8.500 men. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2022;94:155-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pepe P, Dibenedetto G, Pennisi M, et al. Detection rate of anterior prostate cancer in 226 patients submitted to initial and repeat transperineal biopsy. Urol Int 2014;93:189-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Overduin CG, Fütterer JJ, Barentsz JO. MRI-guided biopsy for prostate cancer detection: a systematic review of current clinical results. Curr Urol Rep 2013;14:209-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Litwin MS, Tan HJ. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Prostate Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2017;317:2532-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan SS, Goonawardene N. Internet Health Information Seeking and the Patient-Physician Relationship: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neal DE, Metcalfe C, Donovan JL, et al. Ten-year Mortality, Disease Progression, and Treatment-related Side Effects in Men with Localised Prostate Cancer from the ProtecT Randomised Controlled Trial According to Treatment Received. Eur Urol 2020;77:320-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marton G, Pizzoli SFM, Vergani L, et al. Patients' health locus of control and preferences about the role that they want to play in the medical decision-making process. Psychol Health Med 2021;26:260-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Angst IB, Kil PJM, Bangma CH, et al. Should we involve patients more actively? Perspectives of the multidisciplinary team on shared decision-making for older patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 2019;10:653-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cohen H, Britten N. Who decides about prostate cancer treatment? A qualitative study. Fam Pract 2003;20:724-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Naji L, Randhawa H, Sohani Z, et al. Digital Rectal Examination for Prostate Cancer Screening in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Fam Med 2018;16:149-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morlando M, Pelullo CP, Di Giuseppe G. Prostate cancer screening: Knowledge, attitudes and practices in a sample of men in Italy. A survey. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186332. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Britten N, Stevenson FA, Barry CA, et al. Misunderstandings in prescribing decisions in general practice: qualitative study. BMJ 2000;320:484-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pepe P, Pennisi M. Targeted Biopsy in Men High Risk for Prostate Cancer: (68)Ga-PSMA PET/CT Versus mpMRI. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2023;21:639-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]