Financial considerations among adult men undergoing vasectomy: cost analysis and modeling of outpatient costs associated with vasectomy

Highlight box

Key findings

• There is a definable range of out-of-pocket cost for an insured patient including outpatient visit, vasectomy procedure and post-vasectomy semen analysis of $384–489.

• The main driver of variability in cost stemmed from facility fee and the insurer contribution toward this cost which broadens the definable range of out-of-pocket cost to $384–1,026.

What is known and what is new?

• Barrier to men pursuing vasectomy is the out-of-pocket cost associated with the procedure and required follow-up.

• A reliable cost model to identify a realistic total cost for men undergoing vasectomy.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Hospitals to publish facility fee-related charges prior to undergoing vasectomy procedure.

• Incorporate cost of procedure discussion during pre-operative vasectomy clinic visits.

Introduction

Vasectomies are a durable and safe method of male sterilization. A variety of techniques used to perform vasectomies include excision and ligation, electrocautery, and mechanical occlusion methods. The setting for vasectomy procedures varies from office settings to ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) to hospital outpatient department (HOPD) with ancillary services like pathology (1). Furthermore, the American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines necessitate only one negative post-vasectomy semen analysis (PVSA) while perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis and use of pathology services are not necessary for vasectomy procedures (2). While the setting and customary practice clinicians may generate some variability in the services rendered (e.g., pathology), healthcare delivery for patients undergoing a vasectomy procedure likely has only minor variability.

The cost of vasectomies remains one of the most important components in patients’ willingness to follow through with the procedure and what provider performs their procedure (3). Unfortunately, there is poor medical literature reflecting accurate out-of-pocket cost for patients undergoing vasectomies. A search of medical and nonmedical literature reveals a potential out-of-pocket cost of a vasectomy procedure from 0 to an expense of above $2,500. One study suggested the average total cost of vasectomies in 2010 was $713 (4). Adjusting for inflation at time of publication, the average cost translates to $1,036.870 but can be from $500 to $1,450 or greater (5). Another study suggested the total average cost of vasectomies for in-office procedures vs. ASC’s are $707 and $1,851, respectively, with a range of $440–2,432 while out-of-pocket expenses were $173 and $356, respectively (6). While these data have demonstrated an uncertainty in estimated total and out-of-pocket cost, the associated non-procedural costs have been less explored. Specifically, the cost associated with initial consultation, PVSA testing, as well as potential future reversal.

PVSA is an additive follow-up appointment to vasectomy procedure total cost. PVSAs are considered the best practice to determine success of vasectomy procedure. Current AUA guidelines recommend the first PVSA to be between 8 and 16 weeks with repeat PVSA every 4–6 weeks until a passing test is achieved (2). These guidelines state that to pass a PVSA, the sample must have absence of sperm in uncentrifuged wet preparation or non-motile sperm count less than or equal to 100,000/mL. Semen analysis is commonly done 3 months after the procedure and is recommended to be after at least 20 ejaculations (7). Compliance with PVSA follow-up appointments has been reported to be as low as between 50% and 65% of men but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports a compliance rate closer to 78% (8). A review study determined 1,026 of 1,114 (92.1%) patients passed their first PVSA examination in accordance to AUA guidelines (7). The same study reported 42 of the 61 (69%) men who underwent a secondary PVSA examination passed repeat testing after 6 weeks (7). A similar study found the 3-month PVSA success rate to be 96% with 51.3% of samples having azoospermia (9). Another study focused on PVSA comparison between 3 months after the procedure vs. 20 ejaculations and found around a 20% difference (62.8% vs. 43.8% azoospermia, respectively) while 16% did not achieve azoospermia by 6 months in either cohort (10). The model used for this study reflects the above information.

Vasectomy reversal (vasovasostomy) is a more technically challenging procedure that is utilized after patients have vasectomy regret. Some common causes of vasectomy regret include death of a child, remarriage, change in financial situations, young age, and alleviating post-vasectomy pain syndrome (11). According to most studies, 3–6% of men seek a vasectomy reversal in their lifetime (11,12). A different study reported higher regret rates in childless men at 4.4% immediately following the procedure and 7.4% at follow-up phone calls years after the procedure (13). While vasectomy regret is uncommon, cost of vasovasostomy is not well studied as a possible contributory role in patient’s decisions to pursue the procedure. Another study suggested the average total cost of vasovasostomy in 1987 ranged from $1,144 for local, outpatient procedures up to $2,066 for general anesthesia and inpatient procedures (14). Adjusting for inflation at time of publication, the average cost translates to a range of $2,947–5,322 (5).

No previous study confidently states a narrow price range or a breakdown of cost (facility fees, procedure fees, follow-up semen analysis, pathology submission, preprocedural visit without following up for procedure itself, etc.) for a vasectomy procedure. This study aims to accurately estimate, with a narrow range of cost variability, the total and out-of-pocket cost for patients undergoing a vasectomy procedure.

Methods

Patient population

Men were recruited as part of a study examining patient decision factors leading them to pursue vasectomy [independent review board (IRB) study #00006827]. A theme emerged from that population that cost uncertainty was an abstract barrier to seeking vasectomy. Two hundred consecutive patients were then queried in the billing system to evaluate out-of-pocket cost.

Cost analysis

Billing data was collected from institutional billing department which includes insurance reimbursement totals and outstanding balance which represents the expected patient contribution to be billed as out-of-pocket cost.

Patients reported the direct cost of medical expenses from two local fertility clinics for PVSA and Labcorp, which did vary based on insurance coverage. Finally, Fellow® has a transparent pricing model at $139 per kit during the study period. Unlike other labs, Fellow® at the time of this cohort did not charge for repeat PVSA in the event of persistent ejaculated sperm.

Clinical pathway

All patients underwent a no-scalpel vasectomy by a single surgeon. Vasectomy was performed in a hospital-attached clinic or a procedure room in an ambulatory surgery center. Both facilities had the potential to charge facility fees which were captured in the cost to patients.

Model

Finally, a Monte-Carlo simulation model was created of a patient pool of 10,000 patients reflective of the variable compliance and success rates of vasectomy. The model was simulated on Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Seattle, WA, USA). Model allowed for a derived total average cost as well as a defined range for each clinically relevant step from decision to pursue consultation for vasectomy to the confirmation of vasectomy success with PVSA. The goal was to examine possible levers to adjust cost associated with vasectomy. Model 1, or the maximum cost model, assumes costs of anesthesia (selected from within patient cohort who had anesthesia provider perform monitored anesthesia care), as well as cost associated with sending vas deferens as a specimen (selected from patients who had selective vas deferens sent for pathology). Model 2, or the minimum cost model, assumes no pathology, no general anesthesia nor monitored anesthesia care, or facility fees. Facility fees, which were up to $500, were included separately in both models with variable insurance coverage. Each model was then run based on variable compliance and success rates of PVSA to evaluate a range of out-of-pocket costs.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the data was conducted within Microsoft Excel. Comparisons between the two groups were performed utilizing a two-sided t-test for continuous variables. A significance level of P<0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant. Mean, median, and interquartile range (IQR) for both models were conducted as well.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. This study did not need IRB approval as no human subjects nor access to any identifiable private health information was involved in the study parameters according to local regulation.

Results

Both models provided a total average cost, as well as a defined range, for each clinically relevant event including clinic visit, vasectomy procedure, and PVSA. The models were adjusted for a 78% compliance of PVSA at post-procedure follow-up appointments as well as PVSA failure rates of 8% at first visit, 4% at second visit, and 3% at third visit.

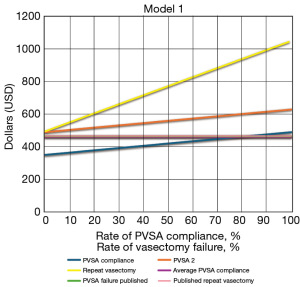

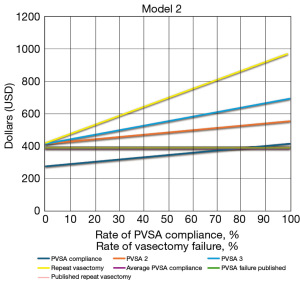

In Model 1, the base out-of-pocket cost was $350 and the cost of PVSA was $139, for an estimated total of $489. PVSA compliance and PVSA failure requiring repeat testing (assuming payment with additional testing) lead to a maximum cost of $767 (Figure 1). The possibility of a repeat vasectomy raised the cost to that individual to $1,043. The Model 1 average cost assuming a 78% PVSA compliance, a 96% PVSA success, and a 1/400 risk of a repeat vasectomy came to $466. Model 1 had a median cost of $478 and an IQR of $443–514. In Model 2, the base cost was $276 and the cost of PVSA was $139, for an estimated total of $415. This difference is reflected in a small cost variability even when factoring in the costs of anesthesia and pathology (the main difference between the models). PVSA compliance and PVSA failure requiring repeat testing (assuming payment with additional testing) lead to a maximum cost of $693 (Figure 2). The possibility of a repeat vasectomy raised the cost to that individual to $969. The Model 2 average cost assuming a 78% PVSA compliance, a 96% PVSA success, and a 1/400 risk of a repeat vasectomy came to $384.42. Model 2 had a median cost of $367 and an IQR of $332–403.

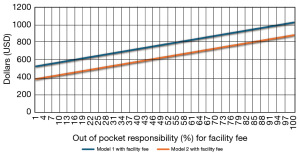

Notably, when incorporating facility fee of $500 with variable insurance coverage (Figure 3), there is a wide range of out-of-pocket cost from $384.42 (full coverage in Model 2) to $1026 (full facility fee out-of-pocket in Model 1). Two-sided t-test performed on Models 1 and 2 average costs revealed a P<0.001 confirming the models are statistically significantly different from one another.

Discussion

Healthcare spending and out-of-pocket expenses for a multitude of urologic procedures are largely under-reported in published literature. Additionally, healthcare spending in the United States is exceedingly higher than any other developed country in the world. With excessive spending, literature reporting of extremely wide range of cost is unhelpful to the average patient whose decision to undergo a vasectomy may rely on out-of-pocket cost.

A significant driver of the wide variable cost for vasectomy procedures are facility fees. In one systematic review of 150 articles investigating the variability drivers of treatment costs for hospitals, 84% of included studies demonstrated that significant differences in procedure costs are explained by variations in facility fees between ambulatory surgery ASC, inpatient, and HOPD settings (15). Some procedures, particularly orthopedic and neurologic surgeries, can have up to a $5,000 difference in facility fees when comparing ASC and HOPD facility fees (16). Depending on insurance type or cash payment, the percent of out-of-pocket cost for the patient for the facility fees can greatly vary. Medicare covers 80% of facility fees while Medicare Advantage Plans does not have a requirement on facility fee coverage and can even deny coverage of facility fees (17). We similarly found facility fees to be the highest driver for out-of-pocket cost variability.

Brant et al. recently published a vastly wide range of self-pay prices for vasectomies in a hospital setting for multiple insurance types using the Turquoise Health database (18). The IQR of commercial insurance prices of vasectomies was listed at $1,032–4,441 with a median commercial price of $2,350 (18). Furthermore, they compared average price for multiple insurance types including Medicaid (median, $955; IQR, $465–1,643) and Medicare Advantage (median, $1,725; IQR, $1,018–1,936) (18). Interestingly, self-price pay had a lower median cost of $1,832 (IQR, $815–3,710) than for commercial insurance pricing (18). However, facility fees were not able to be deduced from the database and were estimated in the study. This estimation may be why the reported price in Brant et al. is notably more expensive than our models suggest.

Additionally, the Turquoise Health database found only 34% of hospitals disclosed pricing of their vasectomy procedures. One potential cause of this lack of transparency is vasectomy procedures are not a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)-specified shoppable service and therefore does not need to be reported by hospitals (19). At common state sponsored ambulatory centers, such as Planned Parenthood, they state a vasectomy procedure could cost up to $1,000 without insurance but do not disclose the breakdown of their estimated pricing (20). This study further highlights the need for published accurate and narrow ranges for procedural pricing and greater transparency in hospital disclosure of pricing breakdown for various procedures.

A similar study by Mortach et al. compared interhospital price variations using the same database used in Brant et al. Mortach et al. reported a similar low disclosure of vasectomy procedure pricing (24.7%) (21). While also publishing prices for certain common insurances, they focused on the cash price for vasectomies at nonprofit hospitals vs for-profit hospitals as well. As expected, nonprofit hospitals had a lower cash price of $1,429.74 compared to for profit hospitals with an average cash price of $3,185.37 (21). Medicaid and Medicare prices were unchanged compared to the Brant et al. study. With a significantly higher average cost for self-pay cash than insurance out-of-pocket expense, this aspect of vasectomy cost artificially increases the average reported price by hospitals for vasectomy procedures.

Cost of PVSA appears to be a potential driver of out-of-pocket cost which is somewhat unique to vasectomy procedure. The usual procedure current procedural terminology (CPT) code for vasectomies is 55250 which bundles the PVSA with the procedure itself (22). In our cohort, there is no in house laboratory to perform this bundled exam. As mentioned in methods, a third-party lab (Labcorp, etc.) is used with variation in costs. This may not be a generalizable cost variable if vasectomy providers have in-house laboratory. Additionally, the code covers “post-operative semen examinations should include all semen specimens needed to determine when the patient has become azoospermia or sterile”, with no sperm seen on a semen specimen smear (22). While PVSA failure (~4%) in published data is rare and does not majorly impact the average cost from an overall system standpoint, it may drive up costs substantially for an individual patient if they receive multiple PVSA after confirmation of azoospermia. An additional caveat to PVSA cost is if the patient was compliant with the initial PVSA at the 3-month post-operative date, commonly required by insurance to cover the cost of PVSA (23). Companies such as Fellow® who do not charge additional fees for additional testing will likely continue to see a competitive advantage in this market.

Many couples consider other contraceptive methods besides vasectomies due to broad price ranges reported and a multitude of other personal decisions. Compared to other contraceptive methods (on aggregate cost for life-time prevention of inception), vasectomy procedures were reportedly lower than most other procedures (3). The prices for these methods were listed as average wholesale price and included Mirena intra uterine device (IUD) at $585 for 5 years, Paragard IUD at $494 for 10 years, Implanon at $627.3 for 3 years, Depo-Provera injections at $75 for 3 months, and tubal ligation at $2,833 (3). There is not well published data for out-of-pocket payment for continued treatment with the contraceptive methods listed above. However, our model suggests vasectomies are the lowest cost contraceptive method for long-term infertility goals.

One aspect of vasectomy costs for patients that is not commonly discussed in other published information is regarding low relative value units (RVUs) compensation for providers. RVUs are a measure used to quantify the value of healthcare services based on the resources required to provide them. The typically used CPT code 55250 for vasectomy procedures yields a RVU of 3.37 (non-facility practice expense RVU of 2.90 and facility practice expense RVU of 6.66) (24). However, standard protocol prior to vasectomy procedure includes a preoperative visit, which yields an additional 2.55–3.74 RVUs, dependent on level three new patient vs. new consultation visit (25). Additionally, there could be a discrepancy in the physician fee for the procedure and amount of PVSAs requested by the physician if performed by a family practice provider vs. a urology provider. One estimate low RVU compensation for vasectomy procedures discourage certain practice models from taking on these patients and therefore could lead private medical practices to increase out-of-pocket price for patients.

Limitations

At our institution, all vasectomy procedures are performed in a surgical procedure area or a hospital attached clinic with associated facility fees. This may artificially inflate the price of the procedure and increase the average cost to patients. We sought to mitigate this with modeling to include a range of cost which would include the absence of facility fee (under assumption of full insurance coverage). Furthermore, costs associated with pathology (not routine) and potentially other costs of anesthesia and independent providers may not be reflected in analysis. Additionally, company policies and pricing may change in the future for PVSA which may be an independent driver of cost not adequately captured in this analysis for longitudinal purposes. Furthermore, insurance coverage of facility fees may vary substantially and is likely poorly captured. The generalizability of this data to private practices may not apply either as the CMS rules do not apply unless affiliated with a hospital.

Conclusions

Based on real-world patient data, there is a narrow range of out-of-pocket cost for an insured patient including outpatient visit, procedure and PVSA between $384 and $466, excluding facility fee ($500 in our cohort). The main driver of variability in cost stemmed from facility fee, insurer contribution toward that cost, and, to a lesser extent, the choice of PVSA testing. Authors recommend that men pursuing vasectomy ask upfront about facility fees to obtain the best cost.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-33/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-33/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-33/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. This study did not need IRB approval as no human subjects nor access to any identifiable private health information was involved in the study parameters according to local regulation.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Strope SA, Daignault S, Hollingsworth JM, et al. Physician ownership of ambulatory surgery centers and practice patterns for urological surgery: evidence from the state of Florida. Med Care 2009;47:403-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharlip ID, Belker AM, Honig S, et al. Vasectomy: AUA guideline. J Urol 2012;188:2482-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bressler J, Landry E, Ward V. Choosing vasectomy: U.S. clients discuss their decisions. AVSC News 1996;34:1, 6.

- Trussell J, Lalla AM, Doan QV, et al. Cost effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States. Contraception 2009;79:5-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI inflation calculator. Available online: http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

- Zholudev V, Khan AI, Patil D, et al. Use of Office Versus Ambulatory Surgery Center Setting and Associated Ancillary Services on Healthcare Cost Burden for Vasectomy Procedures. Urology 2019;129:29-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal A, Gupta S, Sharma RK, et al. Post-Vasectomy Semen Analysis: Optimizing Laboratory Procedures and Test Interpretation through a Clinical Audit and Global Survey of Practices. World J Mens Health 2022;40:425-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belker AM, Sexter MS, Sweitzer SJ, et al. The high rate of noncompliance for post-vasectomy semen examination: medical and legal considerations. J Urol 1990;144:284-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Korthorst RA, Consten D, van Roijen JH. Clearance after vasectomy with a single semen sample containing < than 100 000 immotile sperm/mL: analysis of 1073 patients. BJU Int 2010;105:1572-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barone MA, Nazerali H, Cortes M, et al. A prospective study of time and number of ejaculations to azoospermia after vasectomy by ligation and excision. J Urol 2003;170:892-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel AP, Smith RP. Vasectomy reversal: a clinical update. Asian J Androl 2016;18:365-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Potts JM, Pasqualotto FF, Nelson D, et al. Patient characteristics associated with vasectomy reversal. J Urol 1999;161:1835-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Charles DK, Anderson DJ, Newton SA, et al. Vasectomy Regret Among Childless Men. Urology 2023;172:111-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belker AM. Vasectomy reversal. Urol Clin North Am 1987;14:155-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacobs K, Roman E, Lambert J, et al. Variability drivers of treatment costs in hospitals: A systematic review. Health Policy 2022;126:75-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Federico VP, Nie JW, Sachdev D, et al. Medicare procedural costs in ambulatory surgery centers versus hospital outpatient departments for spine surgeries. J Neurosurg Spine 2024;40:115-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. What does Medicare cost? Available online: http://www.medicare.gov/basics/get-started-with-medicare/medicare-basics/what-does-medicare-cost

- Brant A, Lewicki P, Zhu A, et al. High variability in self-pay pricing for vasectomy and vasectomy reversal in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2024;56:98-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid programs: CY 2020 hospital outpatient PPS policy changes and payment rates and ambulatory surgical center payment system policy changes and payment rates. Price transparency requirements for hospitals to make standard charges public. Fed Regist 2019;84:65524-606.

- Planned Parenthood. Where Can I Buy a Vasectomy & How Much Will It Cost? Available online: https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/birth-control/vasectomy/how-do-i-get-vasectomy

- Mortach S, Sellke N, Rhodes S, et al. Uncovering the interhospital price variations for vasectomies in the United States. Int J Impot Res 2024; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- CPT code 55250 - excision procedures on the vas deferens. Available online: https://www.aapc.com/codes/cpt-codes/55250?srsltid=AfmBOoq7i3KfKCdYG-s-NypdYJU3eZC0Hv--QA6-9-ir3vtJeqxVPERT

- DeRosa R, Lustik MB, Stackhouse DA, et al. Impact of the 2012 American Urological Association vasectomy guidelines on postvasectomy outcomes in a military population. Urology 2015;85:505-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Labor. OWCP medical fee schedule: effective table of RVU & conversion factor values by CPT/HCPCS codes. 2021. Available online: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OWCP/regs/feeschedule/fee/feejune302021/EffectiveJune302021-CPT_HCPCS_ADAandOWCPCodeswithRVUandConversionFactors.pdf

- AAPC. Avoid losing up to $125 in vasectomy-related payment with this 4-step coding process. 2009. Available online: https://www.aapc.com/codes/coding-newsletters/my-urology-coding-alert/avoid-losing-up-to-125-in-vasectomy-related-payment-with-this-4-step-coding-process-article