Mirabegron efficacy as medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral stones: a systematic review of the literature, meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis

Highlight box

Key findings

• This meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 419 patients found that mirabegron does not significantly improve stone expulsion rate, expulsion time, or analgesic use compared to placebo in patients with 5–10 mm distal ureteral stones. Trial sequential analysis suggests that the current evidence is close to the futility boundary, and one well-designed RCT may be sufficient for a conclusive result.

What is known and what is new?

• Previous studies suggested potential benefit of mirabegron in stone expulsion due to its β3-adrenergic action on ureteral smooth muscle, though results were conflicting and often based on heterogeneous study designs.

• This is the first meta-analysis including only RCT evaluating mirabegron versus placebo for medical expulsive therapy (MET) in distal ureteral stones. This manuscript provides high-level evidence that mirabegron, as a standalone MET, does not offer significant benefit in stone passage or pain relief in the setting of 5–10 mm distal ureteral calculi. It also incorporates trial sequential analysis to assess the conclusiveness of current data.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Mirabegron should not be recommended as standard MET for distal ureteral stones at this time. Future well-powered RCTs are needed to definitively determine its clinical utility. Guidelines should remain cautious in adopting mirabegron for ureterolithiasis until stronger evidence is available.

Introduction

Renal stone disease is a highly prevalent disease. Data from the United States show rates of 8.8%, being higher among male individuals, 10.6% compared to 7.1% in women. The most common symptoms include abdominal pain and nausea (1). For stones between 5 and 10 mm, medical expulsive therapy (MET) can be performed (2). This approach reduces the risk of surgical approach and the stone expulsion time (SET) (2,3). MET can be performed through the use of alpha-adrenergic blockers and calcium channel blockers or prostaglandin E2 or F2 synthesis inhibitors such as diclofenac. The demonstration of the presence of β3-agonist receptors in the ureter of humans and animals in a previous study as a relaxing activity in the ureter encourages the evaluation of their efficacy for MET in distal ureteral stones (4).

The European Association of Urology (EAU) and American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines on urinary stones do not mention the use of mirabegron as expulsion therapy for ureteral stones. However, there is work on the subject. Previous meta-analyses assessed the use of mirabegron for the treatment of ureteral stones and suggested benefits in stone expulsion rate (SER) and pain control. Nevertheless, studies show conflicting evidence on the subject (2,3,5). The study by Samir et al. (2024) did not demonstrate superiority in the use of mirabegron for MET of stones in the distal ureter (6). Abdel-Basir Sayed et al. (2022) found superiority of treatment with mirabegron + ketorolac when compared to ketorolac, with better results in SET and pain episodes (7).

The purpose of the study is to assess the effectiveness of the use of mirabegron versus placebo in the treatment of distal ureter stones between 5 to 10 mm through the first meta-analysis composed exclusively of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the topic and perform a trial sequential analysis (TSA) on our assessed outcomes. We present this article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-112/rc).

Methods

Eligibility criteria

This study was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42023494126). A search was conducted at PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane databases from its inception to December 2023 to identify RCTs reporting the comparison of mirabegron and placebo as MET for distal stones from 5 to 10 mm (Figure 1).

This meta-analysis included RCTs that evaluated the efficacy of mirabegron as a MET in adult patients with distal ureteral stones measuring 5 to 10 mm. Studies were eligible if they compared mirabegron to placebo or an alternative MET regimen and reported at least one of the following outcomes of interest: SER, SET, or analgesic use.

Exclusion criteria included: (I) non-randomized studies, including retrospective analyses and case reports; (II) studies involving proximal or mid-ureteral stones; (III) trials where mirabegron was combined with other MET agents without a clear control group; (IV) studies lacking sufficient outcome data for meta-analysis; and (V) studies including patients with conditions that could interfere with MET outcomes, such as severe hydronephrosis, urinary tract infections, significant renal impairment, pregnancy, or prior urological surgery.

The included trials followed standardized imaging protocols using non-contrast computed tomography (CT) or kidney-ureter-bladder (KUB) radiography to confirm stone presence and passage. Follow-up durations varied between studies but ranged from 4 to 7 weeks.

Search strategy and data extraction

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to December 2023 with the following search terms: (‘distal ureteral stones’ OR ‘distal ureteric stones’ OR ‘ureteral stones’ OR ‘urolithiasis’ OR ‘ureteral calculi’) AND (‘expulsive therapy’) AND (‘Mirabegron’ OR ‘β3-adrenergic agonist’’). Zotero was utilized to remove any duplicate studies. Two independent researchers (R.D.d.L. and L.S.d.A.) conducted a screening of titles and abstracts to eliminate irrelevant studies. Following this process, the full text was reviewed to select the included studies. Any disagreements were solved by a third reviewer (J.A.S.d.C.).

Quality assessment

Two authors (B.C.P. and L.S.d.A.) independently extracted the data based on a predefined protocol, and disagreements were solved by a third author (J.A.S.d.C.). Risk of bias was assessed in randomized studies using version 2 of the Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool (RoB 2) (Figure 2).

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed by the R+ Rstudio [RStudio Team (2023). Rstudio: Integrated Development for R. Rstudio, PBC, Boston, MA, USA]. Continuous outcomes are presented as a mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Dichotomous data are presented as risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI. Pooled estimates were calculated with the random-effect model, considering that the patients came from different populations. For all statistical analyses, a two-sided value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The I2 statistic and the P value tests were used to assess heterogeneity. We used TSA to evaluate the sample size and whether the sample present in our study would be able to prove the hypotheses evaluated.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

The search retrieved 36 articles, of which five RCTs met the inclusion criteria, comprising a total of 419 patients, 204 in mirabegron branch and 215 in placebo group. The remaining 31 studies were excluded after full-text screening for the following reasons: duplicate reports (n=19), exclusion based on title or abstract (n=7), comparison of mirabegron with combined therapy instead of placebo or standard MET (n=2), ongoing trial status (n=1), and other reasons (n=2). Most studies followed patients for up to four weeks, except for one study that extended follow-up to seven weeks. The administered dose of mirabegron was consistently 50 mg daily across all studies (Table 1).

Table 1

| Study | Design | Mirabegron dose | Number of patients | Age (years), mean (SD) | Males (%) | Stone size (mm), mean (SD) | Duration (weeks) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirabegron | Control | Mirabegron | Control | Mirabegron | Control | Mirabegron | Control | |||||||

| Bayar et al., 2020 (8) | RCT | 50 mg | 29 | 36 | 43 (13.3) | 39.1 (14.6) | 85.7% | 76.2% | NA | NA | 4 | |||

| Morsy et al., 2022 (4) | RCT | 50 mg | 30 | 30 | 47.2 (4) | 43.8 (16.7) | 64% | 76% | 6.5 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) | 7 | |||

| Rajpar et al., 2022 (9) | RCT | 50 mg | 40 | 41 | 28.8 (6.4) | 28.7 (8.2) | 57% | 56% | 6.7 (1.5) | 6.5 (1.5) | 4 | |||

| Samir et al., 2024 (6) | RCT | 50 mg | 57 | 60 | 39.5 (10.5) | 41.7 (11.7) | 47.4% | 58.3% | 7.2 (1.6) | 7.3 (1.4) | 4 | |||

| Abdel-Basir Sayed et al., 2022 (7) | RCT | 50 mg | 48 | 48 | 43.2 (10.4) | 41.2 (10.5) | 72.9% | 68.7% | 6 (1.1) | 5.9 (2) | 4 | |||

SD, standard deviation.

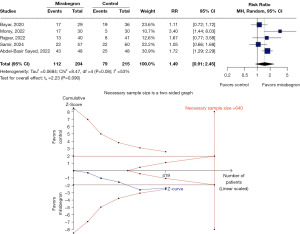

SER

Mirabegron did not show a statistically significant difference compared to placebo in SER (RR 1.49, 95% CI: 0.91–2.45, P=0.08, I2=53%) (Figure 3). TSA indicated that additional RCTs are needed to reach conclusive evidence. However, the cumulative data suggest that a single additional well-powered RCT might be sufficient to clarify the effect of mirabegron on this outcome.

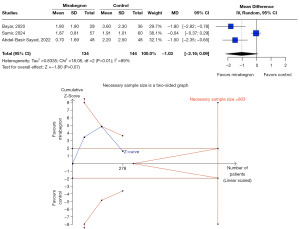

SET

No significant reduction in SET was observed with mirabegron use compared to placebo (MD −1.92 days, 95% CI: −5.38 to 1.54, P=0.28, I2=95%) (Figure 4). TSA indicated that a larger sample size is necessary to determine the true impact of mirabegron on SET.

Pain episodes and analgesic use

Three RCTs assessed analgesic use, and one RCT evaluated the frequency of pain episodes. No significant difference was found between groups regarding analgesic consumption (MD −1.03 doses, 95% CI: −2.16 to 0.09, P=0.07, I2=89%) (Figure 5). Regarding pain episodes, mirabegron also failed to demonstrate a significant advantage over placebo. TSA confirmed that the current sample size is insufficient to draw definitive conclusions on this endpoint.

Discussion

In our meta-analysis, we included 419 patients from 5 different RCTs comparing mirabegron and placebo as MET in patients presenting 5 to 10 mm distal ureteral stones. We observed that mirabegron was not superior to placebo when it came to SER and SET.

The use of MET is based on the presence of different receptors spread throughout the urinary tract (8), mainly in the distal ureter. A previous study has shown, through immunohistochemical methods, the presence of β3-agonist receptors in the urothelium and ureter and the potential for relaxation of the ureter through the stimulation of these receptors (10).

As ureteral dilation occurs, there is a downregulation of expression of β3-agonist receptors, favoring contraction and spasm of the ureter (10). Based on these findings, numerous authors have favored mirabegron to facilitate the passage of ureteral stones (5,11-13). Nevertheless, our meta-analysis did not benefit in the use of mirabegron for distal ureteral stones of 5 to 10 mm.

The last previous meta-analysis, conducted by Cai et al. (2022) (5), gathered 398 cases from three RCTs and a retrospective study, and their group analysis showed that the SER in the group treated with mirabegron was higher than in the control group. The inclusion of non-RCTs may have contributed to the divergent results, whereas our study included only RCTs.

Abdel-Basir Sayed et al. (2022) (7) found a higher SER in the mirabegron group compared to the control group (89.6% vs. 52.1%, respectively), also, the SET was inferior in the intervention group. Other RCTs from 2022 showed higher SER in the group treated with mirabegron and diclofenac compared with the group treated only with diclofenac. Meanwhile, there was no difference in SET (14). In the present meta-analysis, there was no difference between the SER or SET between the mirabegron and the placebo groups.

One of the pioneering articles regarding the use of mirabegron as MET showed that there was a reduction in the use of analgesia in the group treated with mirabegron plus diclofenac compared to the diclofenac group (5). Solakhan et al. (2019), on the other hand, observed that the use of rescue analgesia for both proximal and middle ureteral stones was similar among the groups, but in the distal stones, it was lower in the mirabegron group compared to the control group. We found no difference between groups regarding rescue analgesia (14).

Our meta-analysis has some limitations. The main limitation is that TSA found that there are still insufficient RCTs for a more consistent analysis of our outcomes. Five studies were evaluated, of which 3 evaluated the use of mirabegron versus placebo and 2 evaluated mirabegron + non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) versus only NSAID. There was no distinction between pain episodes and medications used in each painful episode. Although the articles are presented in a low-key manner, the absence of information about the randomization method of most studies may provide some undetected bias to the study (Figure 5) (15). Also, we must note that adverse events were not systematically reported across all included RCTs, limiting our ability to perform a comprehensive safety analysis. While mirabegron is generally considered safe, future studies should provide more consistent reporting on potential side effects in this setting.

Furthermore, it is important to highlight that lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are commonly associated with distal ureteral stones, and mirabegron is a well-established treatment for overactive bladder. However, our study specifically focused on its potential role in stone expulsion rather than its effect on LUTS. Future studies could explore whether the use of mirabegron in this context offers additional symptomatic benefits beyond its potential expulsive effects.

Conclusions

We found no evidence that mirabegron benefits MET for distal ureteral stones from 5 to 10 mm. Further RCTs are needed to establish the true role mirabegron may have in ureterolithiasis.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this article has been published in XVIII Paulista Congress of Urology - Poster Section - São Paulo, 2024.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-112/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-112/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-2025-112/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Stamatelou K, Goldfarb DS. Epidemiology of Kidney Stones. Healthcare (Basel) 2023;11:424. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Assimos D, Krambeck A, Miller NL, et al. Surgical Management of Stones: American Urological Association/Endourological Society Guideline, PART I. J Urol 2016;196:1153-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pearle MS, Goldfarb DS, Assimos DG, et al. Medical management of kidney stones: AUA guideline. J Urol 2014;192:316-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morsy S, Nasser I, Aboulela W, et al. Efficacy of Mirabegron as Medical Expulsive Therapy for Distal Ureteral Stones: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Controlled Study. Urol Int 2022;106:1265-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cai D, Wei G, Wu P, et al. The Efficacy of Mirabegron in Medical Expulsive Therapy for Ureteral Stones: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Clin Pract 2022;2022:2293182. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Samir M, Awad AF, Maged WA. Does mirabegron have a potential role as a medical expulsive therapy in the treatment of distal ureteral stones? A prospective randomized controlled study. Urologia 2024;91:136-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Basir Sayed M, Moeen AM, Saada H, et al. Mirabegron as a Medical Expulsive Therapy for 5-10 mm Distal Ureteral Stones: A Prospective, Randomized, Comparative Study. Turk J Urol 2022;48:209-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bayar G, Yavuz A, Cakmak S, et al. Efficacy of silodosin or mirabegron in medical expulsive therapy for ureteral stones: a prospective, randomized-controlled study. Int Urol Nephrol 2020;52:835-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajpar ZH, Memon II, Soomro KQ, et al. Comparison of the Efficacy of Medical Expulsive Therapy for the Treatment of Distal Ureteric Stones with and without Mirabegron. J Liaquat Uni Med Health Sci 2022;21:11-5.

- Malin JM Jr, Deane RF, Boyarsky S. Characterisation of adrenergic receptors in human ureter. Br J Urol 1970;42:171-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Otsuka A, Shinbo H, Matsumoto R, et al. Expression and functional role of beta-adrenoceptors in the human urinary bladder urothelium. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2008;377:473-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shen H, Chen Z, Mokhtar AD, et al. Expression of β-adrenergic receptor subtypes in human normal and dilated ureter. Int Urol Nephrol 2017;49:1771-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Michel MC. β-Adrenergic Receptor Subtypes in the Urinary Tract. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2011;307-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solakhan M, Bayrak O, Bulut E. Efficacy of mirabegron in medical expulsive therapy. Urolithiasis 2019;47:303-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. [Crossref] [PubMed]