International volunteerism and global responsibility

Introduction

“Generosity is giving more than you can, and pride is taking less than you need.”—Khalil Gibran

To do something for others, without the expectation of a return is volunteering. It is considered an altruistic activity done “to benefit another person, group or organization”. The verb was first recorded in 1755. It was derived from the noun volunteer, in C. 1600, “one who offers himself for military service”, from the Middle French voluntaire (1).

Skills-based volunteering such as urology is leveraging the specialized skills and the talents of individuals to benefit those who do not have access to these services due to economical or other reasons (2). While the efforts in general are noble and well-intended in most instances, the field of the medical adventures (referring to volunteers who travel overseas to deliver medical care) has recently attracted negative criticism when compared to the alternative notion of sustainable capacities, i.e., work done in the context of long-term, locally-run, and foreign-supported infrastructures. A preponderance of this criticism appears largely in scientific and peer-reviewed literature. Recently, media outlets with more general readerships have published such criticisms as well (3).

The need is in low and middle income countries (LMIC) a term used by WHO as opposed to developing countries or third world used in the past. Many of these countries have pockets of excellence in urological care but may lack such care outside the main cities, or for want of necessary equipment and/or formal training. Thus, the missions can be varied, providing surgical direct care, building a program for sustained training and clinical care, equipment donation and finally preventive care. Each of these missions needs a different pathway and modus operando.

Providers are largely from the western world; however manpower and local volunteers are keys to the success of any mission. In this article we describe models in urology, the role of local hosts, ethical standards or lack there off, personal experiences, effort data with particular emphasis on resident participation and finally, how to get started in this arena. Please note that at the end of the review, there is a list of surgical missions: dos and don’ts (4).

Organizations and the output

- The Global Philanthropic Committee (GPC) supports proposals for worthy projects to improve urologic care throughout the developing world. The committee is a partnership between the multi-national urology organizations, American Urological Association (AUA), European Urology Association (EAU), and the Société Internationale d’Urologie (SIU). The idea, initiated by Dr. Robert Flanigan of the AUA enables organizations to pool their resources to fund larger scale philanthropic projects as a collaborative effort. Urology organizations can support a project through monetary funds and/or in-kind donations, including volunteer time. The inaugural project supported by the GPC was the creation of two regional, urology training centers in sub-Saharan Africa that serve multiple countries. One center is in Ibadan, Nigeria and the other is in Dakar, Senegal. The established sites have provided measurable outcomes and will continue to provide and build training capacity. The project continues to require urologists to donate their time to educate local surgeons and urologists on a variety of subject areas. Other efforts include those in East Africa and the joint effort with Haiti described later in this article. GPC has partnered with IVUmed and Urolink (5).

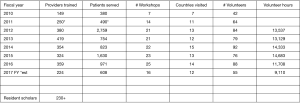

- IVUmed is a nonprofit organization nurtured by Dr. Catherine DeVries, based in Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. IVUmed (formerly International Volunteers in Urology), incorporated in 1995, is a leading NGO in teaching urology in LMICs (6). In fulfilling this mission, IVUmed provides medical and surgical education to physicians and nurses and treatment to thousands of suffering children and adults. IVUmed’s mission is to teach the teachers as well as provide grants for residents to participate in these missions. This approach ensures the long-term sustainability of programs and fosters the professional independence of IVUmed’s partners abroad. The output over the years is listed in Figure 1. IVUmed in addition to fund rising, has been a recipient of grants from AUA and many of the sections of the AUA, the Gates Foundation among others. Its well-structured staff is a resource for many who wish to get involved (7).

- Urolink is an effort closely linked to the British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS). The evolution stems from 1983, when there was a proposal to form a Tropical Urology Society. In 1985, BAUS proposed the establishment of links with the Association of Surgeons of East Africa and, in 1986, while President of BAUS, Professor John Blandy invited suggestions for providing assistance to the “Third World”. In 1988, Professor Geoff Chisholm facilitated a “Tropical/Third World” meeting which, ultimately, led to BAUS members being canvassed about the setting up of Urolink. By 1990, a working party had been formed, Urolink was adopted and its aims defined. In 1996, Urolink became a sub-Committee of BAUS and one of the BAUS trustees now sits on the Urolink Committee (8).

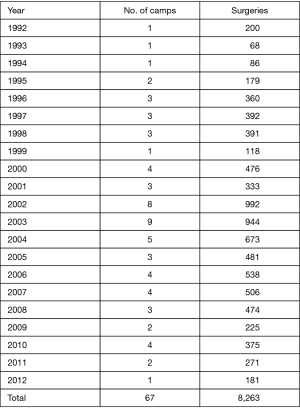

- Jeev Sewa Sansthan (JSS), an NGO based in Bhopal, India has been involved in providing support for urological surgical missions since 1992. It provides financing, volunteers and organizational structure for the visiting teams throughout north India, in addition to Ophthalmic camps to cataracts. The clinical cases done over the years are listed in Figures 2,3 (9).

- International Organization for Women and Development (IOWD), established by Barbara and Ira Margolis, has its focus on leading a team of specialists in Female Pelvic health to sub-Saharan Africa (Niger, Rwanda) for fistula and incontinence care. The IOWD team has the experience to deal with the government in the US as well as locally, thus facilitating the difficult terrain and logistics needed to provide care in remote locations (10,11).

- US Military: US Navy hospital ship humanitarian assistance and disaster response also provides a unique educational opportunity for young military surgeons to experience various global health systems, diverse cultures, and complex logistical planning without sacrificing the breadth and depth of surgical training. This model may provide a framework to develop future international electives for other general surgery training programs (12,13).

Models of effort

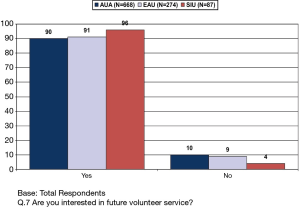

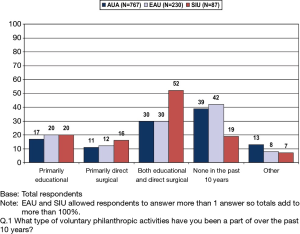

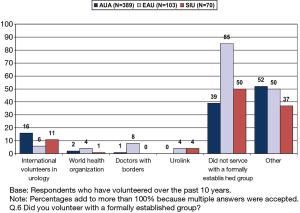

A survey conducted by the GPC showed a tremendous desire to volunteer (Figures 4,5,6), but the efforts were mostly individual and many were not aware of the organizations providing a structure. Individual efforts lack the scrutiny needed to avoid harm both to the provider and the recipient. Background knowledge of local culture, medical licensure, and prophylaxis from disease states, malpractice protection and protocol for evacuation in a medical emergency are key elements in preparation of a successful mission trip.

- Service model: many efforts are individual or through religious organizations. While personally satisfying they are limited in their scope. A team on the other hand is typically from the western world, is credentialed, facilitated by an organization and may be funded or self-funded by its members. In the host country it is paramount to have a local urologist or surgeon who will provide the screening and after care for these patients. Visit to the same site is best, to keep improving rather than going to different sites and facing the same problems repeatedly. The local organization/group other than the physician is the key to success. The Circumcision program in Namibia through the AUA and volunteers has had a measurable decline in STD and HIV.

- Teaching model: the motto established by Mahatma Gandhi of teaching versus giving is echoed by IVUmed in its mission statement of “Teach one and reach many”. A shining example of this is a center established in Ajmer, India. This a urology care center established in 1997 in a joint effort by the local government, the medical school, JSS the NGO and Indian urologist from USA with IVUmed. The local urologist was awarded a visiting scholarship followed by donation of equipment as well as visiting urology teams with experts in subspecialty. Over the years it has grown to a sixty bed fully operational center which serves thousands of patients per year. It is now ready to be an approved teaching center for local residents.

- Establishing a center for ongoing service: well thought out program planning, a shared vision among the program site, the coordinating NGO, and a supporting organization such as GPC facilitate the development of thriving surgical teaching programs capable of serving local communities and conducting outreach training. Examples of these are the centers in Dakar, Senegal (14). The other more recent is the effort in Haiti, as paraphrased from the report prepared by the AUA staff, “The Societe Haitienne D’Urologie (SHU) and Global Association for the support of Haitian Urology (GASHU) consisting of the AUA, SIU, individually and as part of GPC, IVUmed, Association des Medecins Haitiens a l’Etranger (AMHE), Genito-Urinary Reconstructive Surgeons (GURS), Project Haiti, Notre Dame Filariasis Project, and Konbit Sante and other individuals signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the University Hospital St. Francois de Sales in Port-au-Prince”. This MOU holds promise to allow more frequent and efficient surgical workshops to take place in Port-au-Prince (Capital of Haiti) while allowing maximum resident participation and better local arrangements for international volunteers.

Ethics and rules of engagement

Health care professionals wanting to help those in need in LMIC is a noble endeavor, it is not without its ethical challenges. Many are just beginning to explore these issues that may come in the wake of charity care in international locations (15). Issues surrounding respect for autonomy include informed consent, adequate screening, and cultural sensitivity. Sometimes the difficulty of working conditions increases the possibility of causing harm, and follow-up care may be lacking or inadequate. Establishing safe surgery has been established in a variety of locations by Haynes et al. (16). Benefits locally may disrupt indigenous standards.

In an excellent overview, Erickson established a table of do and don’t (4). Friedman et al. published 27 principles that should be addressed (15).

Value

To the individual patient in a LMIC receiving care, the value is immense as otherwise they may not receive care at all or not the same expertise. Providing endoscopic, minimally invasive approaches to common urologic conditions such as BPH or stone disease can mean a few days away from work versus several weeks of morbidity from an open incision. The value to the one providing the care in general is measurable only in the emotional well-being or self fulfilment, but the humanitarian setting allows significant exposure to learning and can play a pivotal role in the resident’s education. Resident participation through the IVUmed has well established over the years (Figure 1) under direct supervision of qualified mentors. The experience unfortunately is not recognized by the ACGME in urology, but a model has been established in general surgery and plastic surgery (17,18). In a survey of incoming interns, as to the interest in global health, response rate was 87% (299 of 345 residents). The most commonly reported barriers to participating in global health experiences were scheduling (82%) and financial (80%) concerns (19).

Personal experience

My journey was initiated by a sense of duty to serve, embedded in me by my parents. “What have you done for the country that gave you free medical education” was a question my father asked after I was well established in academic medicine in the early nineties. In my reflection, I realized I was serving only myself. A chance meeting with spiritual leader of JSS in Bhopal, India started me on this journey. Role models like Sakti Das and Catherine DeVries at the IVUmed paved the path for doing it in an organized manner. The cooperation between IVUmed and JSS was smooth as silk. The ripple effect led to meeting other groups like IOWD and work in Niger. Next was the unique opportunity to lead the AUA and be part of the GPC (Figure 7). So many individuals and most importantly industry partners (Olympus, Storz, Cook Urological, Laborie just to name a few leading players) have contributed generously. The nursing staff at many hospitals that collect disposable items that are not used could have filled many a shipping containers. The effort of many goes unnoticed because they want it to be such, but what I would urge is the need for an organized effort, as it is exponential in terms of value by a team effort, almost like compounding interest.

Conclusions

There is a great desire on the part of many urologists and residents to serve as volunteers in a humanitarian effort. Multinational urology organizations have taken the lead to organize and assist in this effort. The NGO’s both in the western world and the host countries provide the boots on the ground to facilitate these efforts. There is unique opportunity for the training of urology residents in not only technical skills but interpersonal relationships and the effective use of resources. ACGME should consider this learning module under the direct supervision of qualified mentors. The SUU/SUCPD should take the lead to petition the RRC in urology to establish an approved curriculum as it exists in other surgical specialties.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jana Trevaskis’s assistance in this manuscript.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Harper D. Online Etymology Dictionary. 2017. Available online: http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=volunteer

- Service NaC. Skills-Based Volunteering. 2017. Available online: www.nationalservice.gov/resources/member-and-volunteer-development/sbv

- Thompson J. Think looking after turtles in Costa Rica for three weeks is good for your CV? Think again. 2017.

- Erickson BA. International surgical missions: How to approach, what to avoid. Urology Times. 2013.

- Association AU. Giving Back: American Urological Association. 2017. Available online: http://www.auanet.org/international/giving-back.cfm

- deVries CR. The IVUmed Resident Scholar Program: aiming to "teach one, reach many". Bull Am Coll Surg 2009;94:30-6. [PubMed]

- IVU. IVUmed. 2017. Available online: http://www.ivumed.org

- BAUS. Urolink | The British Association of Urological Surgeons Limited. 2017. Available online: http://www.baus.org.uk/professionals/urolink/default.aspx

- Sansthan JS. Jeev Sewa Sansthan. 2017. Available online: https://www.jeevsewa.org/

- Kay A, Idrissa A, Hampton BS. Epidemiologic profile of women presenting to the National Hospital of Niamey, Niger for vaginal fistula repair. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;126:136-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- IOWD. IOWD | Committed to a fistula free world. 2017. Available online: http://www.iowd.org/

- Licina D, Mookherji S, Migliaccio G, et al. Hospital ships adrift? Part 2: the role of US Navy hospital ship humanitarian assistance missions in building partnerships. Prehosp Disaster Med 2013;28:592-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jensen S, Tadlock MD, Douglas T, et al. Integration of Surgical Residency Training With US Military Humanitarian Missions. J Surg Educ 2015;72:898-903. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jalloh M, Wood JP, Fredley M, et al. IVUmed: a nonprofit model for surgical training in low-resource countries. Ann Glob Health 2015;81:260-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Friedman A, Loh L, Evert J. Developing an ethical framework for short-term international dental and medical activities. J Am Coll Dent 2014;81:8-15. [PubMed]

- Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 2009;360:491-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tarpley M, Hansen E, Tarpley JL. Early experience in establishing and evaluating an ACGME-approved international general surgery rotation. J Surg Educ 2013;70:709-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mackay DR. Obtaining Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Approval for International Rotations During Plastic Surgery Residency Training. J Craniofac Surg 2015;26:1086-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Birnberg JM, Lypson M, Anderson RA, et al. Incoming resident interest in global health: occasional travel versus a future career abroad? J Grad Med Educ 2011;3:400-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]