Urethral diverticulum carcinoma in females—a case series and review of the English and Japanese literature

Introduction

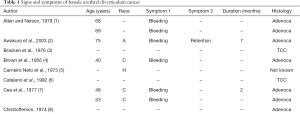

Urethral diverticulum carcinoma (UDC) in women is extremely rare with only 123 cases previously reported (Table 1). Relatively little is known about UDC in women. We detail three additional cases of UDC in women and review the literature on the subject to more clearly define patient characteristics, presenting symptoms, diagnostics, treatments and outcomes to determine optimal management strategies.

Full table

Methods

We performed a literature search using the keywords; urethral diverticulum, cancer, carcinoma, tumour and malignancy. Databases searched were Medline, EMBASE and the Cochrane library. The data collected included patient demographics, presenting symptoms, diagnostic investigations, treatment modality and outcome at last follow-up in terms of disease free survival, recurrence and mortality. Ethnicity was determined according to the Office of National Statistics recommendations (79). For our own case series, we retrospectively reviewed patient records to glean symptoms at presentation, diagnostic modalities utilised, pathological stage and grade and management. Written informed consents were obtained from the patients for publication of their cases and any accompanying images.

Case presentations

Case 1

A 38-year-old Arabic female presented with an 18-month history of a palpable vaginal lump, dysuria, dyspareunia, urinary dribble, mixed urinary incontinence (UI), urinary tract infections (UTIs) and pain during urination. Per vaginal examination revealed a palpable hard and indurated mass.

Trans urethral (TUR) biopsy performed prior to referral revealed inflammation only. Pre-operative pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a circumferential complex urethral diverticulum (UD) and videourodynamics (VUDS) indicated the presence of both idiopathic detrusor overactivity (IDO) and bladder outflow obstruction (BOO).

Initial management was excision of the UD with a modified Martius labial fat pad flap (MFP). Histological examination demonstrated a G3 adenocarcinoma of the UD with positive vaginal and proximal margins. She was counseled regarding all treatment and reconstructive options and went on to have a radical cystourethrectomy, pelvic lymph node dissection and ileal conduit formation 4 weeks after preliminary diverticulum excision. Formal histological analysis revealed a pT3N0M0 G3 adenocarcinoma. She remains under surveillance and is alive with a solitary lung recurrence at 72 months post diverticulectomy.

Case 2

A 55-year-old black female presented with a 9-month history of dysuria, urethral pain and poor flow. Clinical examination revealed a palpable non-tender vaginal mass. MRI pelvis showed a circumferential loculated complex UD and VUDS indicated the presence of BOO. Transvaginal biopsy indicated inflammation only.

She proceeded to excision of the UD with MFP interposition. Histological examination revealed pT2 G3 adenocarcinoma of the UD with negative margins. Formal staging with CT chest, abdomen and pelvis and bone scan indicated her to be N0M0. She was counseled regarding all treatment options and declined any further therapy. She died from metastatic adenocarcinoma 22 months following her diverticulectomy.

Case 3

A 52-year-old black female presented with an 8-month history of dysuria, dyspareunia, UTIs and urethral pain. On clinical examination she had a palpable vaginal mass.

She underwent simple excision of her UD at her local hospital and was referred when histological review revealed a pT3 G2 adenocarcinoma with positive urethral margins. Post excision MRI performed at our centre indicated partial excision of a circumferential complex UD. Additional staging with CT chest, abdomen and pelvis and bone scan indicated that she was N0M0. After full counseling regarding treatment options she elected to undergo radical urethrectomy, bladder neck closure with MFP interposition, pelvic lymph node dissection and formation of Mitrofanoff channel. Histological examination of the excised specimen confirmed pT3N0 G2 adenocarcinoma. She remains alive and disease free at 21 months post diverticulectomy.

Epidemiology

Primary urethral carcinoma in females is extremely rare, accounting for only 0.02% of genitourinary tract malignancies (2-6). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) predominates, accounting for 70% of urethral carcinoma, followed by urothelial (20%) and then clear cell adenocarcinoma (CCA) (10%) (1,3,78,80,81).

UDC represents just 5% of all female urethral carcinoma or 0.001% of female genitourinary tract malignancies (81,82). Unlike in primary urethral carcinoma, adenocarcinoma is the commonest type of UDC, accounting for 75% of UDC (Tables 1-4). Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) (15%) is the next most common and SCC the least common (10%) (9,16,42,59). The first patient with UDC was reported by Hamilton in 1951 (24), and since then only 124 cases (including the 3 in this current series) have been reported in the world literature.

Full table

Full table

Full table

Female urethral diverticula are in themselves rare entities—affecting between 0.02–6% of the female population (83,84). First described in 1805, they are benign, localized, epithelium-lined urethral outpouchings (85,86). Histologically, they are difficult to distinguish from paraurethral cysts. Their lining is composed of squamous epithelial cells in 42%, columnar epithelial cells in 32%, a combination of both squamous and columnar cells in 18% and cuboidal cells alone in 14% (87). The majority of diverticula (77%) show signs of inflammation, and ulceration is often present (87).

Rarely, diverticula are congenital, arising from embryonic Gartner duct remnants, persistence of Müllerian rest cells or the faulty union of primordial folds (88). The majority of diverticula are acquired; arising from rupture of chronically obstructed and infected periurethral glands into the lumen of the urethra (89,90). Risk factors for the development of urethral diverticula are: recurrent infection of the periurethral glands, vaginal birth trauma and previous vaginal or urethral surgery (91-95).

Pathogenesis

There are 3 theories regarding the origin of UDC (15,81,94). The first is that they arise from periurethral gland changes occurring due to persistent/continued infection and obstruction to drainage (20,21,61). The second theory suggests a metaplastic origin with neoplastic squamous, glandular or TCC development resulting from chronic inflammation and urethritis glandularis (65). The final theory is that the malignant change originates in retained Gartner or mesonephric duct remnants (78,96).

Many UDC are considered to originate from the paraurethral duct, which may be homologous to the prostate gland because it is prostate-specific antigen (PSA) positive in some cases (33,42,97). Ogihara and Kato suggested that the adenocarcinomas that arise from urethral diverticula are either CEA-positive columnar and/or mucin-producing and originate from the proximal portion of the paraurethral duct, or are PSA positive clear cell-type arising from the distal part of the paraurethral duct (96).

Occasionally premalignant lesions such as villous adenomas, intestinal metaplasia and high-grade dysplasia may arise (9,65). There are very occasional instances of benign tumour, such as leiomyoma and nephrogenic adenoma (9,65).

Age and race

The median age at presentation of UDC is 53 years (range, 14–81 years). There may be a higher incidence in the black population, possibly related to the higher incidence of UD amongst black women (9,21) although this is disputed (25). Our latest review of the literature indicates that 38% of cases are in white women, 32% in black women, 22% in Asian women and 8% in Hispanic women (N=65). In our series of 100 women having UD excision 82% with benign UD were white whilst UDC was found in 2 black and 1 Asian female suggesting a preponderance of UDC in black and Asian women. The median age of presentation of women with benign diverticulum also tended to be younger than those with UDC at 44 years (N=97). This contrasts with a median age at diagnosis of 53 in those with UDC (N=3) (98).

Presentation

There are no pathognomonic signs and symptoms of UDC. As can be seen in Table 1 UDC may present with signs and symptoms of UD—classically dysuria (13%), dyspareunia (7%) and/or post micturition dribble/UI (3%). UDC more commonly presents with urethral bleeding or hematuria in 55%, urethral obstruction/voiding dysfunction in 16%, urethral/introital mass in 13%, UTIs in 13% and localized pain in 6% (N=89). A painless mass of the anterior vaginal wall can be found on examination in the majority of patients (1,9,16,80,81,90,96). This mass may feel much like a benign diverticulum but is noted to be firm or hard in some cases.

Preoperative diagnosis of UDC remains difficult because of its nonspecific presentation. The differential diagnosis of a peri-urethral mass in women includes; UD, urethrocele and/or cystocele, vaginal inclusion cyst, Müllerian cyst, endometriosis, and urethral or vaginal carcinoma. (33,61,81,88,97).

Diagnosis

Diagnostic modalities used in the diagnosis and pre-operative planning of UDC are outlined in Table 2. Urine cytology may be a useful initial screening test and has been reported to be positive in 10/11 (91%) cases in which it was utilised (2,25,31,36,41,42,45,60,69,71,77,96,98). Imaging modalities that have been used to aid the diagnosis of UDC include ultrasound, intravenous urography, voiding cystourethrography, computed tomography (CT), MRI, and cystourethroscopy (2,9,25,31,36,41,45,60,69,71,77,80,96,98,99). The gold standard investigations to date appear to be a combination of gadolinium-enhanced MRI which can be used for diagnosis, staging and surveillance followed by transvaginal trucut or transurethral biopsies of the UD mass for definitive diagnosis. Case 2 above describes a 55-year-old lady with UD diagnosed on an initial MRI (Figure 1) with a follow up contrast enhanced study 2 months later (Figure 2). The differential diagnosis of increasing debris or thickening within the diverticulum includes infection and inflammatory change within the UD and biopsies may yield no evidence of malignancy as in 2/3 of our UDC cases. Cystoscopy was unhelpful in our cases but may play an important role in the pathological diagnosis and in localization of the tumor origin (1) with neoplasm in the diverticulum or urethra noted on cystoscopy in 23/29 (79%) cases in those series reporting its use (7,9,10,12,21,23,31,42,53,54,57,72,73,77,96,98,100).

A CT or an isotope bone scan may be used to assess for lymph node enlargement, distant tissue and bone metastasis (80). In our experience a T2 weighted thin slice post void pelvic MRI should be performed to diagnose the presence of a UD and if history, examination or MRI are suspicious for cancer an urgent urethral diverticulectomy should be performed as a definitive “excision biopsy”.

Pathology

Macroscopically

There is usually a mass within the diverticulum, which may be encroaching into the true urethral lumen or invading past the diverticulum walls into the surrounding paraurethral or paravaginal tissues (80).

Microscopically

Whilst only 10% of urethral cancers are adenocarcinoma, 30% of these originate from UD (1,3,78,80,81). Adenocarcinoma has two subtypes; clear cell and mucin producing (33). The microscopic features of the CCA are similar to those of other CCA of the female genital tract and include; cells with abundant clear cytoplasm, some forms of pleomorphism, mitotic activity and a mostly flat shape. Focally, a hobnail appearance may be present. CCA of a UD may present patterns that are either tubule-cystic, papillary or diffuse (78). In a urine sample, the presence of malignant clear cells with the appearance of mirror balls is highly suggestive for CCA arising from UD (9,16,42).

TCC accounts for around 15% of UDC and is histologically the same as that originating in the bladder although with a tendency to be of a higher stage at diagnosis due to the absence of a muscle layer within a UD. SCC is the least common form of UDC. SCC may be associated with the presence of calculus in a UD; Clayton found this to be the case in 56% (9).

Staging

Staging of UDC is very difficult because of the location of the periurethral glands inside the periurethral space abutting the paravaginal fascia. The TNM staging system has been used in some cases (83). Most cancers are at an advanced stage at diagnosis because there is little muscle underlying them; 83% of UDC were T2 and above at time of presentation in the 54 patients in whom the stage was known at diagnosis (Table 3) (9,16,99). They also tend to be high grade with 73% grade 2 or 3 at presentation (N=40) (9,16,99).

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment is surgical with the options including:

- Urethral diverticulectomy alone or with adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy (9,36,100);

- Urethrectomy +/− pelvic or inguinal lymph node dissection +/− adjuvant therapy (31,81);

- Anterior exenteration (excision of the urethra, bladder, anterior vaginal wall, uterus and pelvic lymph nodes) +/− inguinal lymph node dissection +/− adjuvant therapy (12,13,31,45,68);

- Radiotherapy +/− adjuvant chemotherapy alone (1,3,9).

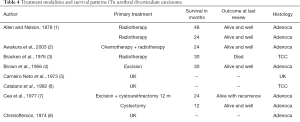

The results from the various treatment options are summarized in Table 4. Accepting the limited (generally < 2 years) length of follow-up in most series, simple urethral diverticulectomy appears to be curative in 55% of the 22 patients who underwent same in which follow up was specified with a further 14% alive with recurrence at a mean of 26 months follow-up (4,9,16,21,22,24,26,36,38,39,41,44,51,52,57,59,66,71,74-76,78). Urethrectomy appears to be curative in 100% at a mean of 13 months follow up (N=3) (30,31,69).

Occasionally cisplatinum-based chemotherapy alone and chemoradiotherapy has been used, without formal documentation of its effectiveness (3,80). Other chemotherapeutic agents utilized include 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin.

Prognosis

Patients with adenocarcinoma and TCC of a UD fare better than those with SCC. The % of patients alive with no evidence of disease (NED) at last follow-up is:

- 72% for those with adenocarcinoma (median 48 months) (N=54);

- 78% for those with TCC (median 18 months) (N=18);

- 25% for those with SCC (median 48 months) (N=12).

Conclusions

UDC is an extremely rare condition and presents a serious situation due to non-specific presentation and delayed diagnosis. UDC needs aggressive treatment as survival is at best moderate and is particularly poor for those with SCC. Optimal treatment remains to be determined but appears to be radical surgery. Consideration should be given to adjuvant radiotherapy +/− chemotherapy in patients with SCC or high-grade adenocarcinoma or TCC. An international registry and consensus on treatment would greatly aid the management of this problematic condition.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Allen R, Nelson RP. Primary urethral malignancy: review of 22 cases. South Med J 1978;71:547-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Awakura Y, Nonomura M, Itoh N, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the female urethral diverticulum treated by multimodality therapy. Int J Urol 2003;10:281-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bracken RB, Johnson DE, Miller LS, et al. Primary carcinoma of the female urethra. J Urol 1976;116:188-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown EW. Diverticulum of the female urethra: report of 23 cases with adenocarcinoma in one. South Med J 1956;49:982-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carneiro Neto J, Sayao RH. Carcinoma and multiple calculi in diverticulum of the female urethra. Rev Paul Med 1973;81:279-82. [PubMed]

- Catalano S, Jones I. Transitional cell carcinoma in a urethral diverticulum. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1992;32:85-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cea PC, Ward JN, Lavengood R, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinomas in urethral diverticulum. Urology 1977;10:58-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Christoffersen I. Development of adenocarcinoma in a diverticulum of the female urethra. Ugeskr Laeger 1974;136:2030-1. [PubMed]

- Clayton M, Siarni P, Guinan P. Urethral Diverticular Carcinoma. Cancer 1992;70:665-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Collado A, Algaba F, Caparros J, et al. Clear cell adenocarcinoma in a female urethral diverticulum. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2000;34:136-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Ruiz M, Pozo-Garcia A, Gene-Heym A, et al. Intra-diverticular adenocarcinoma of the urethra in women. Presentation of a new case. Actas Urol Esp 2010;34:916-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis R, Peterson AC, Lance R. Clear cell adenocarcinoma in a female urethral diverticulum. Urology 2003;61:644. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis JW, Scellhammer PF, Schlossberg SM. Conservative surgical therapy for penile and urethral cancer. Urology 1999;53:386-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prudente de Toledo W, Montellato NI, Arap S, et al. Carcinoma in diverticulum of the female urethra. Urol Int 1978;33:393-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dodson MK, Cliby WA, Pettavel PP, et al. Female urethral adenocarcinoma: evidence for more than one tissue of origin? Gynecol Oncol 1995;59:352-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Evans KJ, McCarthy MP, Sands J. Adenocarcinoma of a female urethral diverticulum: case report and review of the literature. J Urol 1981;126:124-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faulkner JW. Primary carcinoma in a diverticulum of the female urethra: review of the literature and report of a case. J Urol 1959;82:337-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geisler E, Basu A, Abughaida A, et al. Mesonephric Carcinoma arising from a Female Urethral Diverticulum. Br J Urol 1998;81:637-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ghoniem G, Khater U, Hairston J, et al. Urinary retention caused by adenocarcinoma arising in recurrent urethral diverticulum. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2004;15:363-5. [PubMed]

- Godec CJ, Anderson WR, Cass A, et al. Urinary retention in female patients induced by adenocarcinoma of urethra. Urology 1984;23:256-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez MO, Harrison ML, Boileau M. Carcinoma in diverticulum of female urethra. Urology 1985;26:328-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Graf EC, Callahan DH, Sozer I. Study of tumors of the female urethra. J Urol 1962;88:64-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ha HK, Lee W, Lee SD, et al. Laparoscopic radical Cystourethrectomy in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the female urethral diverticulum. Korean J Urol 2010;51:145-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamilton JD, Leach WB. Adenocarcinoma arising in the diverticulum of the female urethra. AMA Arch Pathol 1951;51:90-8. [PubMed]

- Hickey N, Murphy J, Hershorn S. Carcinoma in a urethral diverticulum: magnetic resonance imaging and sonographic appearance. Urology 2000;55:588-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hinman F Jr, Cohlan WR. Gartner’s duct carcinoma in a urethral diverticulum. J Urol 1960;83:414-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hruby G, Choo R, Lehman M, et al. Female clear cell adenocarcinoma arising within a urethral diverticulum. Can J Urol 2000;7:1160-3. [PubMed]

- Huvos AG, Muggia FM, Markewitz M. Carcinoma of female urethra. Occurrence with hyperparathyroidism. N Y State J Med 1969;69:2042-5. [PubMed]

- Jensen KM, Mygind H, Nielsen KK. Cancer in an urethral diverticulum. Review of the literature and report of 2 cases. Ugeskr Laeger 1981;143:2485-7. [PubMed]

- Jimenez de León J, Luz Picazo M, Mora M, et al. Intra-Diverticular Adenocarcinoma of the urethra in women. Arch Esp Urol 1989;42:931-5. [PubMed]

- Kanno T, Moroi S, Okuno H, et al. A case of adenocarcinoma arising in female urethral diverticulum. Hinyokika Kiyo 2002;48:235-7. [PubMed]

- Kasahara R, Tabei T, Tsuura Y, et al. Female Urethral Diverticulum Carcinoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Urol 2017;2017. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kato H, Ogihara S, Kobayashi Y, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen positive adenocarcinoma of a female urethral diverticulum: case report and review of the literature. Int J Urol 1998;5:291-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klotz PG. Carcinoma of Skene’s gland associated with urethral diverticulum: a case report. J Urol 1974;112:487-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lang EK, Sethi E, Ordonez A, et al. Adenocarcinoma of suburethral diverticulum. J Urol 2008;179:728. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manning J. Case report: transitional cell carcinoma in situ within a urethral diverticulum. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23:1801-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murayama T, Komatsu H, Asano M, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the urethra in a woman: report of a case. J Urol 1978;120:500-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marshall S, Hirsch K. Carcinoma within urethral diverticula. Urology 1977;10:161-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McLoughlin MG. Carcinoma in situ in urethral diverticulum: pitfalls of marsupialization alone. Urology 1975;6:343. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Melnick JL, Birdsall TM. Carcinoma of a diverticulum of the female urethra. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1960;80:347-52. [Crossref]

- Nakamura Y, Takahashi M, Suga A, et al. A case of adenocarcinoma arising within a urethral diverticulum diagnosed only by surgical specimen. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1995;40:69-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakatsuka S, Taguchi I, Nagatomo T, et al. A case of clear cell adenocarcinoma arising from the urethral diverticulum: Utility of urinary cytology and immunohistochemistry. Cytojournal 2012;9:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ney C, Miller HL, Ochs D. Adenocarcinoma in the diverticulum of the female urethra: a case report of mucous adenocarcinoma with a summary of the literature. J Urol 1971;106:874-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noguchi S, Ida T. Carcinoma in diverticulum of female urethra--a case report and review of the literature. Hinyokika Kiyo 1983;29:921-9. [PubMed]

- Okubo Y, Fukui I, Sakano Y, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma arising in the female urethral diverticulum. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 1996;87:1138-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oliva E, Young RH. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra: a clinicopathologic analysis of 19 cases. Mod Pathol 1996;9:513-20. [PubMed]

- Patanaphan V, Prempree T, Sewchand W, et al. Adenocarcinoma arising in female urethral diverticulum. Urology 1983;22:259-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajan N, Tucci P, Mallouh C, et al. Carcinoma in female urethral diverticulum: case reports and review management. J Urol 1993;150:1911-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reheis JP, Goldstein IS, Mogil RA. Papillary adenocarcinoma arising in a urethral diverticulum accompanied by adenocarcinoma of the bladder: case report and review of the literature. J Urol 1981;126:695-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rhamy RK, Boldus RA, Allison R, et al. Therapeutic modalities in adenocarcinoma of the female urethra. J Urol 1973;109:638-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld LJ, Fruchtman B. Carcinoma in diverticula of the female urethra. Obstet Gynecol 1964;24:924-7. [PubMed]

- Roth AA. Carcinoma of the female urethra. Ohio State Med J 1955;51:872-4. [PubMed]

- Salvador Álvarez E, Alvarez Moreno E, Jimenez de la Pena M, et al. Malignant degeneration in a urethral diverticulum: uncommon complication in a common condition. Radiologia 2011;53:266-9. [PubMed]

- Scantling D, Ross C, Jaffe J. Primary clear cell adenocarcinoma of a urethral diverticulum treated with multidisciplinary robotic anterior pelvic exenteration. Case Rep Med 2013;2013. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schileru G, Bussey J, Carter EF 3rd. Primary infiltrating adenocarcinoma in a female. Acta Urol Belg 1984;52:439-42. [PubMed]

- Schnoy N, Leistenschneider W. Tumor of mesonephric origin in a diverticulum of the urethra. An ultrastructural study. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol 1982;397:335-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seballos RM, Rich RR. Clear cell adenocarcinoma arising from a urethral diverticulum. J Urol 1995;153:1914-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sekowska J, Golajewski A. Primary cancer of a diverticulum of the female urethra. Pol Przegl Chir 1961;33:1470-2. [PubMed]

- Shalev M, Mistry S, Kernen K, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma in a female urethral diverticulum. Urology 2002;59:773. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sheahan G, Vega Vega A. Primary clear cell adenocarcinoma in a female urethral diverticulum: a case report and review. World J Nephrol Urol 2013;2:29-32.

- Srinivas V, Dow D. Transitional cell carcinoma in a urethral diverticulum with a calculus. J Urol 1983;129:372-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tanabe ET, Mazur MT, Shaeffer A. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the female urethra: clinical and ultrastructural study suggesting a unique neoplasm. Cancer 1982;49:372-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tesluk H. Primary adenocarcinoma of female urethra associated with diverticula. Urology 1981;17:197-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas RB, Maguire B. Adenocarcinoma in a female urethral diverticulum. Aust N Z J Surg 1991;61:869-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas AA, Rackley RR, Lee U, et al. Urethral diverticula in 90 female patients: a study with emphasis on neoplastic alterations. J Urol 2008;180:2463-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thompson IM, Bivings FG. Aspects of urethral carcinoma. J Urol 1962;87:891-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tines SC, Bigongiari LR, Weigel JW. Carcinoma in diverticulum of the female urethra. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982;138:582-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torres SA, Quattlebaum RB. Carcinoma in a urethral diverticulum. South Med J 1972;65:1374-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uesaka Y, Kato T, Nakai Y, et al. A case of clear cell adenocarcinoma arising from a female urethral diverticulum. Hinyokika Kiyo 2011;57:639-42. [PubMed]

- von Pechmann WS, Mastropieta MA, Roth TJ, et al. Urethral adenocarcinoma associated with urethral diverticulum in a patient with progressive voiding dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188:1111-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Washino S, Terauchi F, Matsuzaki A, et al. A case of adenocarcinoma in female urethral diverticulum. Hinyokika Kiyo 2007;53:593-6. [PubMed]

- Weng WC, Wang CC, Ho CH, et al. Clear cell carcinoma of female urethral diverticulumd -a case report. J Formos Med Assoc 2013;112:489-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wheeler JS Jr, Flanigan RC, Hong HY, et al. Female urethral diverticular with clear cell adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol 1992;49:66-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wishard WN Jr, Nourse MH. Carcinoma in diverticulum of female urethra. J Urol 1952;68:320-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wishard WN Jr, Nourse MH, Mertz J. Carcinoma in diverticulum of female urethra. J Urol 1960;83:409-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wishard WN Jr, Nourse MH, Mertz J. Carcinoma in diverticulum of female urethra. J Urol 1963;89:431-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamagiwa K, Yamamoto S, Sawada Y, et al. Adenocarcinoma arising in diverticulum of female urethra- a case report and review of the literature. Hinyokika Kiyo 1988;34:1239-43. [PubMed]

- Young RH, Scully RE. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the bladder and urethra. A report of three cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 1985;9:816-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Accessed Dec 2017. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Revisions-to-the-Standards-for-the-Classification-of-Federal-Data-on-Race-and-Ethnicity-October30-1997.pdf

- Kawashima A, Sandler CM, Wasserman NF, et al. Imaging of urethral disease: a pictorial review. Radiographics 2004;24:S195-216. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Venyo AK. Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma of the Urethra: Review of the Literature. Int J Surg Oncol 2015;2015. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maier U, Dorfinger K, Susani M. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the female urethra. J Urol 1998;160:492-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andersen MJ. The incidence of diverticula in the female urethra. J Urol 1967;98:96-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El-Nashar SA, Bacon MM, Kim-Fine S, et al. Incidence of female urethral diverticulum: a population-based analysis and literature review. Int Urogynecol J 2014;25:73-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hey W. Practical Observations in Surgery. Philedelphia: James Humphreys, 1805:303-5.

- Davis HJ, Telinde RW. Urethral diverticula: an assay of 121 cases. J Urol 1958;80:34-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsivian M, Tsivian A, Schreiber L, et al. Female urethral diverticulum: a pathological insight. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2009;20:957-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glassman TA, Weinerth JL, Glenn JF. Neonatal female urethral diverticulum. Urology 1975;5:249-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Routh A. Urethral diverticulum. Br Med J 1890;8:360-5.

- Cocco AE, MacLennan GT. Unusual female suburethral mass lesions. J Urol 2005;174:1106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clemens JQ, Bushman W. Urethral diverticulum following collagen injection. J Urol 2001;166:626. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kumar D, Kaufman MR, Dmochowski RR. Case reports: periurethral bulking agents and presumed urethral diverticula. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22:1039-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Athanasopoulos A, McGuire EJ. Urethral diverticulum: a new complication associated with tension-free vaginal tape. Urol Int 2008;81:480-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hammad FT. TVT can also cause urethral diverticulum. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2007;18:467-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tancer ML, Ravski NA. Suburethral diverticulum. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1982;25:831-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ogihara S, Kato H. Endocrine cell distribution and expression of tissue-associated antigens in human female paraurethral duct: Possible clue to the origin of urethral diverticular cancer. Int J Urol 2000;7:10-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pollen JJ, Dreilinger A. Immunohistochemical identification of prostatic acid phosphatase and prostate specific antigen in female periurethral glands. Urology 1984;23:303-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fontaine CL, Iatropoulou D, Pakzad M, et al. Pathological Findings in Urethral Diverticulum and Possible Pathogenesis of Urethral Diverticulum Cancer. ePoster presentation ICS 2017.

- Ahmed K, Dasgupta R, Vats A, et al. Urethral diverticular carcinoma: an overview of current trends in diagnosis and management. Int Urol Nephrol 2010;42:331-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Young D, Billello S, Gomelsky A. Squamous cell carcinoma in situ in a female urethral diverticulum. South Med J 2007;100:537-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]