Breast cancer and sexual function

Introduction

In the United States, breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, regardless of race or ethnicity. Fortunately, more women are surviving their diagnosis, likely as the combined result of earlier detection and better therapies. As a result, over three million women have a history of breast cancer, making them the largest proportion of cancer survivors in the United States alone (41% of the entire population of cancer survivors) (1).

Chief among the issues faced by these women are those related to sexual dysfunction, which can occur during treatment and extend into long-term survivorship. In one study that included 83 breast cancer survivors (all of whom were 3 or more years after diagnosis) surveyed using the female sexual function index (FSFI) and the female sexual distress scale-revised (FSDS-R), 77% qualified for the diagnosis of sexual dysfunction on the FSFI alone (2). In another study by Ganz and colleagues, over 760 women who had participated in an earlier survey responded to a follow-up questionnaire, with an average time between survey points of 6.3 years (3). This study revealed that while physical and emotional functioning had normalized, sexual function remained compromised with a reduction in sexual activity with their partner compared to the initial survey (65% to 55%) and persistent vaginal dryness, and urinary incontinence. Finally, the importance of sexual health in cancer survivorship was shown in the 2010 survey conducted by LiveStrong (4). In that survey that included over 3,000 people (24% with breast cancer, 41% one to five years post-treatment), sexual functioning and satisfaction were ranked the third most frequently reported concern. Despite this, less than half had received medical care. More importantly, sexual concerns resulted in significant emotional distress, including sadness/depression, issues related to personal appearance, stigma, and negative impacts on personal relationships.

In this article, we will provide a review on sexuality and intimacy issues after treatment for breast cancer, including both the physical and emotional effects experienced by survivors, and the barriers of effective treatment with discussion of solutions to improve overall survivorship. Whenever possible, we will refer to only the most recent data based on randomized trials, to illustrate the scope of this issue and the available options for diagnosis and treatment.

Although not meant to be comprehensive systematic review of the literature, we aim to provide the reader with a view on this topic and illustrate a practical approach to treatment, based on our approach at the Oncology Sexual Health Clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA, USA).

While the article may be considered most relevant to heterosexual women in relationships, we hope that the issues discussed are placed in a more general context and hence, are relevant to all women diagnosed with breast cancer, regardless of sexual orientation and current partner status. However, the issue of sexuality for men with breast cancer is beyond the scope of this review.

Background

Female sexual function encompasses more than just arousal and orgasm; it is informed by multiple domains and other factors (Figure 1). These include desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain, body image, psychological health, and sensuality. Many of these areas are queried on sexuality-specific questionnaires, including the one used by this author, the FSFI.

Several models of female sexual function have been characterized in the literature. Basson et al. attempted to incorporate the importance of psychological and mental health into the concept of female sexuality by proposing that intimacy, desire, arousal, orgasm, and satisfaction were all part of a propagating circle-separate, inter-related, and all equally important (5). Manne and Badr discussed sexuality as a multi-compartmental model that governed intimacy and sexuality, particularly as it related to women in relationships (6). Finally, Perelman described sexual response in terms of a “tipping point”, from which a self-designed threshold is set and once reached, elicits a sexual response (7). Even in this model, the tipping point is subject to influences by both psychosocial and physical factors. All of these models highlight the importance of thinking of sexual health as a global concept, not one that is synonymous solely with sexual activity. While there is no consensus as to which one is universally applicable to women treated for breast cancer, patients at our center are educated about the interplay between intimacy, stimuli, and satisfaction using the Basson model. As we shall discuss, every aspect of the cancer experience can disrupt these components of female sexual health leading to sexual dysfunction.

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual now characterizes sexual health as three entities: disorders of sexual interest and arousal; difficulty with orgasm; and disorders associated with genito-pelvic pain/penetration (8). However, it is important to note that more than one area of concern may be present given the interconnectedness of the domains that encompass female sexual health. More importantly, the diagnosis of any of these must meet criteria that mark them as not just a “nuisance” but also a disorder. This includes: presence of symptoms for at least six months; self-reported and clinically significant distress; and not otherwise explained by a non-sexual condition (including other medical condition or secondary to substance or medication use); severe relationship distress; or other stressors.

It is important to note that changes in sexual health can be related to changes in either the patient or her partner (or both), whether it be related to changes in cosmesis, sensuality, or function. The end result may be a lack of engagement, partly as a result of a heightened sense of the risk of rejection. Fortunately, the available data suggest that of patients who are married, the majority remain stable after a diagnosis of breast cancer (9).

Impact of treatment on sexual health

Surgery

The treatment of breast cancer necessitates surgery of the breast and axilla, which can result in long-term issues both physically and mentally. In a recent prospective study of women with early-stage breast cancer, postoperative sexual function was notably worse when compared to their baseline pre-operative scores (10). This was predominantly due to issues related to arousal following breast conserving surgery while desire, arousal, and difficulty with orgasm were reported by those who underwent mastectomy. However, when scores were compared to age-matched healthy controls, only those women who had undergone mastectomy had significantly more problems related to sexual dysfunction.

Similar results were seen in a study involving almost 1,000 women who were evaluated at regular intervals over five years following surgical treatment for breast cancer (11). Women treated with mastectomy reported more disruption in their lives and significantly lower scores in body image, role, and sexual domains. Of more concern, while some issues improved over time, sexual functioning was not one of them.

While some studies suggested that breast reconstructive surgery is associated with improved sexual health (12,13), other studies suggest this may not be the case. For example, Atisha et al. reviewed responses of 173 women (116 who underwent an immediate reconstruction and 57 with a delayed reconstruction) who answered preoperative and 2-year follow-up surveys (12). Both body image and psychosocial well-being were improved from the preoperative scores, suggesting that women were doing well, regardless of surgical reconstructive decision. However, in another study that compared women who had undergone reconstruction (immediate or delayed) to those who did not, there were no significant differences in either quality of life, sexual functioning, cancer-related distress, body image, anxiety or depression identified one year after surgery (14).

Radiation therapy (RT)

For most women treated with breast conserving surgery and those with high-risk features that warranted mastectomy (including those in whom neoadjuvant chemotherapy was chosen in lieu of primary surgery), RT is an essential part of therapy. However, RT can result in locoregional issues, including persistent breast pain, arm and shoulder discomfort and loss of flexibility, and lymphedema, and any of them are associated with reduction in sexual function (15-18). In a recent survey of over 600 patients who underwent implant breast reconstruction, 219 of whom had prior RT, those who had RT reported lower satisfaction and health-related quality of life compared to those who did not undergo RT (16). These deficits included worse scores in sexual well-being and breast satisfaction. Despite these findings, teasing out the exact contribution of RT to overall sexual health in breast cancer survivors is difficult, given that it is almost always a part of an interdisciplinary cancer treatment program involving both surgery and medical therapies, which have been both more closely tied to issues related to sexual health and function in women.

Chemotherapy

Although there is a major push towards personalized medicine, a large proportion of patients with breast cancer will undergo adjuvant chemotherapy, which for women who were not yet menopausal includes a risk of chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure and onset of an early menopause, which may include issues related to sexual dysfunction. In addition, agents such as the anthracyclines and taxanes can negatively affect global physical function, reducing interest, arousal, and desire. This includes common physical toxicities resulting from chemotherapy include fatigue, alopecia, gastrointestinal distress, and myelosuppression.

While most women will experience improvement once chemotherapy ends, for others, the symptoms persist beyond end of treatment. In one study, 35 women completed a battery of questionnaires after surgery, after chemotherapy (or at least 6 months of endocrine therapy), and then at one year (19). Sexual functioning, desire, arousal, and quality of partnered relationships were shown to decline after chemotherapy when compared to baseline, and these changes persisted out to one year. Of note, these changes were not associated with worsening sense of body image. In a separate cross-sectional study that included 534 women, (69% of whom had received chemotherapy), chemotherapy was associated with both depression and unmet sexual needs (20). These findings were predominantly reported acutely (<1 year from end of treatment) but appeared to recur later (>3 years out from treatment).

Endocrine therapy

The options for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancers include an aromatase inhibitor (AI) for 5 years or tamoxifen for 5 years followed by 5 additional years of either tamoxifen or an AI (21). Although premenopausal women were not considered candidates for an AI (which require non-functional ovaries), the option of ovarian suppression plus an AI is now an alternative option to tamoxifen (plus or minus ovarian suppression) (22).

While an important aspect of treatment in these patients, sexual health is often and negatively impacted. Estimates vary, but approximately 30% to 40% of women treated with tamoxifen report sexual complaints, while over 50% of those on an AI report issues related to sexual health. In addition to primary impacts on sexuality, these agents are tied to the onset or worsening of menopausal type symptoms.

In a survey of over 180 women, Morales et al. showed that both agents significantly increased both the occurrence and the severity of hot flashes (23). While AIs significantly increased the risk of dyspareunia, tamoxifen significantly reduced sexual interest, showing that despite their different profiles, both agents can negatively impact female sexual health. More importantly, they reported that women at younger ages were significantly more likely to experience toxicities.

That AIs cause more sexual (and vaginal) side effects was shown in a study by Baumgart and colleagues (24). In this study, patients without a history of cancer who were either currently (n=54) or not currently taking estrogen (n=48) were compared to women taking tamoxifen (with or without estrogen, n=47) and those taking an AI (with or without estrogen, n=35). Although the proportion of women reporting they were sexually active was similar (60% to 65% across all groups), Women on an AI had significantly lower sexual interest than the two control groups taking estrogen (40% vs. 60%, P<0.05-0.001) or not taking estrogen (40% vs. 68%, P<0.05-0.01). Women on an AI also had significantly greater issues with other aspects of sexual function, such as insufficient lubrication (74%) and dyspareunia (57%), and reported general dissatisfaction with their sex lives (42%). For women on tamoxifen, the corresponding figures were 40%, 31%, and 18%, respectively. Of note, orgasmic dysfunction was not statistically different among women on an AI or tamoxifen (50% vs. 42%), though was higher when compared to controls taking or not taking estrogen (31% and 37%, respectively).

Similar results were obtained in a survey of 129 women conducted by Schover et al. that queried the sexual health of women taking an AI during the first two years of therapy (25). Although the vast majority were adherent to medications, 93% met criteria for sexual dysfunction on the FSFI and 75% reported distress as a result. Of concern, almost a quarter of those women who were sexually active at the initiation of therapy ceased having sex with their partner as a result. Whether sexual function remains problematic throughout the duration of endocrine therapy (and beyond its discontinuation) is not entirely clear as these studies were done while women were taking treatment. More studies are needed to determine the longitudinal impact of endocrine therapy on sexual function, which should include premenopausal women at the time of diagnosis.

Barriers to discussion of sexual health

Despite the prevalence of sexual health toxicities in women treated for breast cancer, estimates are that less than half will seek and/or receive medical evaluation. This is probably multi-factorial, as patients may be unwilling to discuss such personal and sensitive topics with their oncologists, and oncologists may not have the background, knowledge, or comfort levels to engage in sexual health discussions. In a recent review, Halley et al. suggested there were at least three barriers to further discussion and treatment of sexual health after breast cancer (26). First, issues related to sexual function as brought up by patients were often restricted to the physical domain by their respective providers, rather than being acknowledged as a more complicated and global issue. Second, patients often were unsure where to turn to discuss these issues, which was particularly problematic for those receiving care in designated cancer-specific centers. Third, access to services during treatment was often not available due to a disconnection between cancer treatment and other medical care. As a result, sexual dysfunction is often an unmet medical complaint.

Addressing sexual function

The approach to sexual health in breast cancer survivors begins with a comprehensive history, including an understanding of the patient’s active medical problems and the medications currently being prescribed. This is important because sexual dysfunction can be a consequence of long-standing comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus) and/or an iatrogenic result of medications (e.g., beta-blockers) (27).

In addition, discussing sexuality necessitates that doctor-patient relationships build on three pillars: open communication; medical understanding; and education (28). We encourage all clinicians to query patients as to their sexual history as part of the routine assessment of new patients. Doing so can provide the patient with comfort in knowing that sexual health is not “taboo” with their providers, and may open them up to communicating issues as they might arise.

Several methods are available to discuss sexual health, including the PLISSIT model of permission, limited information, specific suggestions, and intensive therapy. However, other ways to engage with patients have been published. Park and colleagues proposed a model of communication based on five A’s—Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange—to discuss and evaluate sexual health (29). Notably, they propose that not all of these tasks require a sole provider to perform; rather, they propose that these issues be done as part of an interdisciplinary effort whenever possible.

For women who do bring up issues related to sexual function, validated questionnaires have proven useful in our practice to not only gage the severity of symptoms, but also to establish a baseline to help gage the impact of any subsequent interventions. While many are available, there is no one “gold standard” tool (30). In a 2013 systematic review, Bartula and Sherman identified three tools that appeared to be most acceptable in terms of their psychometric properties: the FSFI, Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASES), and the sexual problem scale (SPS) (30).

Of available tools, we screen for sexual issues using the FSFI at each visit. We also screen for depression and general quality of life with additional questionnaires. In our practice, gaging both for global quality of life and the presence of depressive symptoms can help contextualize sexual health concerns and determine whether other experts may be of benefit to the individual patient. For example, a patient that high score for depression may benefit from referral to psychiatric or psychological support, especially since depression and sexual dysfunction are among the most common symptoms affecting breast cancer survivors and often overlap (31).

The approach to sexual health also requires specific evaluations of intimacy, as it is an inherent part of sexuality and often overlooked. Intimacy can be described as the emotional connection or closeness, which can occur even in the absence of sexual activity (or the “coital imperative”). The importance of intimacy was underscored by work done by Perz et al. in which over 40 patients, their partners, and their providers were queried (32). They confirmed that as clinicians, we often view sexual health concerns in the physical domain. However, patients and their partners emphasized that intimacy in its own right was important and that for some, even in the absence of a physical and sexual relationship, intimacy was not only important, it was highly valued.

Addressing issues related to sexual health in breast cancer survivors

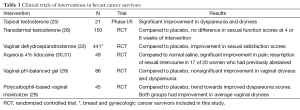

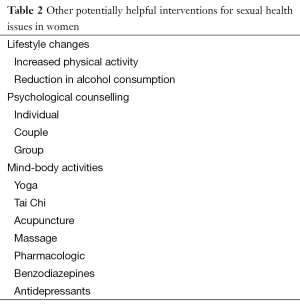

The sexual health issues for women with breast cancer can be addressed. Unfortunately, a review of the contemporary literature shows how few clinical trials have been performed and published for these patients (Table 1). What follows below are the limited data gleamed from clinical trials in this population. Several reviews that provide a more comprehensive discussion of sexual health therapeutics for women (not exclusively focused on women treated for breast cancer) can be found elsewhere and are summarized in a table (Table 2) (33,34).

Full table

Full table

For many women, sexual dysfunction is a symptom of menopause and its associated physical changes in the vulvar and vaginal areas. Atrophy and dryness are common and can make sexual encounters painful, resulting in both dyspareunia and loss of desire. Although the most effective treatment is estrogen replacement therapy (ERT), it is often not the first choice for treatment, particularly for the woman with an intact uterus and those who are on antiestrogen therapies. Alternatives to oral ERT include vaginal specific preparations, such as vaginal estrogen tablets or creams and the use of testosterone (which can be supplied as intradermal or an intravaginal preparation). However, the data on either of these are limited. As an example, a phase I/II study of topical testosterone (150 to 300 mcg cream applied intravaginally) was evaluated among 21 breast cancer survivors with reports that treatment improved both dyspareunia and vaginal dryness (35). Despite this, a randomized trial of transdermal testosterone preparation versus placebo in predominantly breast cancer survivors was conducted by the North Central Cancer Treatment Group and showed testosterone showed no improvement in sexual function compared to placebo (36). At this time, we do not administer testosterone preparations in women treated for breast cancer, unless as part of a clinical investigation. A randomized trial evaluating the safety and tolerability of intravaginal testosterone (1 percent cream) versus vaginal estrogen (2 mg estrogen ring) in 75 women with early stage breast cancer taking an AI has completed (NCT00698035). We await these results to characterize the impact of testosterone specifically among women on an AI.

Whether vaginal estrogen therapy is safe remains controversial. However, at least one study suggests there is no associated risk for recurrence. In this observational study that utilized the United Kingdom General Practice Research database, women with recurrent breast cancer on endocrine therapy were evaluated for the risk of recurrence based on whether or not they had been additionally prescribed vaginal estrogen therapy (37). Their population consisted of women treated with tamoxifen (n=10,806), AIs (n=2,673) and also those who had been treated with vaginal estrogen therapy (n=271). They did not find an association between vaginal estrogen therapy and recurrence risk (RR 0.78, 95% CI, 0.48-1.25). The clinical trial mentioned above (NCT00698035) will further address the safety of a vaginal estrogen preparation, specifically among women taking an AI; however, longitudinal follow-up of this trial will be necessary to help address concerns regarding relapse and survival associated with vaginal estrogen.

Another hormonal intervention evaluated in a randomized clinical trial is dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), which was compared to placebo in the Alliance Cooperative Group N10C1 clinical trial (38). In this trial, 441 women were randomly assigned to DHEA administered as a vaginal preparation (at 3.25 or 6.5 mg doses) compounded in a bioadhesive vaginal moisturizer or to the bioadhesive moisturizer alone. As presented, all women had improvements from their baseline regardless of treatment arm. However, compared to no DHEA, women receiving DHEA had statistically significant improvements in sexual function at 12 weeks based on their FSFI scores. The most common side effects associated with DHEA included headaches and voice changes.

Non-hormonal interventions have been proven to be effective in this population, especially the use of vaginal moisturizers. In one study of 86 patients, a 12-week course of a vaginal pH-balanced gel was compared to a placebo preparation (39). Compared to placebo, the vaginal gel significantly reduced vaginal pH and enhanced vaginal maturation. In addition, treatment improved both vaginal dryness and dyspareunia scores. Similar results were obtained in a study of a polycarbophil-based vaginal moisturizer versus placebo among 45 women with breast cancer (40). There was trend towards improved dyspareunia scores with the vaginal moisturizer, although notably, both preparations were associated with improvements in vaginal dryness (62% and 64% in the placebo and moisturizer groups, respectively).

For some patients who experience pain with penetrative intercourse, one potential therapy is aqueous lidocaine, particularly if the site of pain is located at the vulvar vestibule. This was shown in a trial conducted by Goetsch et al. that randomly assigned 49 postmenopausal patients with a history of breast cancer to an aqueous 4% lidocaine preparation or normal saline, applied for 3 minutes to tender areas before activity (41). Aqueous lidocaine had a significant impact on worst pain score (from median of 5 to 0) whereas normal saline had only minimal relief (median 6 to 4). In this trial, side effects were minimal and of note, the partners of patients on this trial had no complaints, and none complained of numbness. Whether this treatment will be effective in patients with evidence of pelvic floor muscle dysfunction or vaginismus is unknown. Still, in a separate report, 37 of 41 women who were treated with open-label lidocaine solution reported comfortable penetration and 17 of 20 women who had abstained from sex had resumed penetrative intercourse (42).

For women who experience pain with penetration not limited to the vestibule, treatment with lubricants and vaginal dilators is indicated. In contrast to moisturizers, lubricants do not change the vaginal pH and environment, but does address issues related to vaginal dryness that can make sexual contact uncomfortable. Although both water-based and silicone-based lubricants are available, there are no data to inform whether one is more useful in breast cancer survivors. Therefore, the choice is often individual and guided by the end results. Vaginal dilators are useful to help overcome pelvic floor muscle responses. While there are no data to inform the efficacy of treatment in a randomized trial setting in this population, one non-randomized study that included 15 women with vestibulodynia showed that treatment significantly improved dyspareunia scores using validated questionnaires, including the FSFI (43).

Beyond medications, some data suggest that vaginal exercise as part of a multimodal treatment plan can be effective. In the Oliver Oil, Vaginal Exercise, and MoisturizeR (OVERcome) trial, 25 women with dyspareunia were instructed to perform pelvic floor muscle exercises twice daily, use a polycarbophil vagina moisturizer three times per week, and use olive oil as a lubricant during sex (44). While not compared to a control arm, the treatment regimen resulted in significant improvements in dyspareunia scores, sexual function, and quality of life. Of those enrolled, 92%, 88%, and 73% of patients rated the pelvic floor exercises, vaginal moisturizer, and olive oil as beneficial, respectively. These data suggest that multimodal treatments play a role in sexual health recovery. Further studies should be performed to determine the benefits of these types of programs in women after cancer.

In addition, some data show that more formal programs in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can provide relief. In one study, 422 patients were randomly assigned to CBT, CBT plus physical exercise, or were assigned to a waiting list (control group) (45). CBT consisted of a 6 weekly group sessions (focused on control of hot flashes and night sweats, as well as issues related to body image, sexuality, and mood) that also included relaxation exercises. The physical exercise component was 12-weeks long and individualized for patients to be active for 2.5 to 3 hours per week. Those patients who participated on the CBT plus physical exercise group had a significant improvement in sexual activity compared to the control group while the CBT only group had significant and sustained improvement in urinary complaints. These data suggest that CBT may help to address sexual health issues among breast cancer survivors; however, further studies are warranted.

Beyond what has been reported in the contemporary literature, education and mind-body therapies can play a significant role in overcoming sexual dysfunction. Whether this is by providing much needed education on her anatomy, explanations on the complexity of the female sexual response cycle, or validation that sexual side effects are not only real but also common, such information (in our experience) can bring about a sense of relief and validation to patients.

Conclusions

As more women continue to survive diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, sexual dysfunction disorders have become an evident challenge for patients among this population. Addressing sexual concerns is in turn becoming an apparent necessity in managing the care of patients with breast malignancies. Among the major challenges existing in clinical practice is the barrier to communication regarding such issues involving both the physician and patient. Identifying and developing treatment plans are essential in improving the quality of life in patients suffering from sexual dysfunction.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: E Boswell has no conflicts of interest to declare. D Dizon is a Deputy Editor at UpToDate.

References

- DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:252-71. [PubMed]

- Raggio GA, Butryn ML, Arigo D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sexual morbidity in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health 2014;29:632-50. [PubMed]

- Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:39-49. [PubMed]

- Challenges reported by post-treatment cancer survivors in the livestrong surveys. Available online: http://www.livestrong.org/what-we-do/our-approach/reports-findings/survivor-survey-report/

- Basson R, Wierman ME, van Lankveld J, et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. J Sex Med 2010;7:314-26. [PubMed]

- Manne S, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples' psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer 2008;112:2541-55. [PubMed]

- Perelman MA. The sexual tipping point: a mind/body model for sexual medicine. J Sex Med 2009;6:629-32. [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. eds. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- Taylor-Brown J, Kilpatrick M, Maunsell E, et al. Partner abandonment of women with breast cancer. Myth or reality? Cancer Pract 2000;8:160-4. [PubMed]

- Aerts L, Christiaens MR, Enzlin P, et al. Sexual functioning in women after mastectomy versus breast conserving therapy for early-stage breast cancer: a prospective controlled study. Breast 2014;23:629-36. [PubMed]

- Engel J, Kerr J, Schlesinger-Raab A, et al. Quality of life following breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy: results of a 5-year prospective study. Breast J 2004;10:223-31. [PubMed]

- Atisha D, Alderman AK, Lowery JC, et al. Prospective analysis of long-term psychosocial outcomes in breast reconstruction: two-year postoperative results from the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study. Ann Surg 2008;247:1019-28. [PubMed]

- Ganz PA. Sexual functioning after breast cancer: a conceptual framework for future studies. Ann Oncol 1997;8:105-7. [PubMed]

- Metcalfe KA, Semple J, Quan ML, et al. Changes in psychosocial functioning 1 year after mastectomy alone, delayed breast reconstruction, or immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:233-41. [PubMed]

- Hidding JT, Beurskens CH, van der Wees PJ, et al. Treatment related impairments in arm and shoulder in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9:e96748. [PubMed]

- Albornoz CR, Matros E, McCarthy CM, et al. Implant breast reconstruction and radiation: a multicenter analysis of long-term health-related quality of life and satisfaction. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:2159-64. [PubMed]

- Ewertz M, Jensen AB. Late effects of breast cancer treatment and potentials for rehabilitation. Acta Oncol 2011;50:187-93. [PubMed]

- Safarinejad MR, Shafiei N, Safarinejad S. Quality of life and sexual functioning in young women with early-stage breast cancer 1 year after lumpectomy. Psychooncology 2013;22:1242-8. [PubMed]

- Biglia N, Moggio G, Peano E, et al. Effects of surgical and adjuvant therapies for breast cancer on sexuality, cognitive functions, and body weight. J Sex Med 2010;7:1891-900. [PubMed]

- Hwang SY, Chang SJ, Park BW. Does chemotherapy really affect the quality of life of women with breast cancer? J Breast Cancer 2013;16:229-35. [PubMed]

- Burstein HJ, Temin S, Anderson H, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2255-69. [PubMed]

- Pagani O, Regan MM, Walley BA, et al. Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;371:107-18. [PubMed]

- Morales L, Neven P, Timmerman D, et al. Acute effects of tamoxifen and third-generation aromatase inhibitors on menopausal symptoms of breast cancer patients. Anticancer Drugs 2004;15:753-60. [PubMed]

- Baumgart J, Nilsson K, Evers AS, et al. Sexual dysfunction in women on adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer. Menopause 2013;20:162-8. [PubMed]

- Schover LR, Baum GP, Fuson LA, et al. Sexual Problems During the First 2 Years of Adjuvant Treatment with Aromatase Inhibitors. J Sex Med 2014;11:3102-11. [PubMed]

- Halley MC, May SG, Rendle KA, et al. Beyond barriers: fundamental ‘disconnects’ underlying the treatment of breast cancer patients' sexual health. Cult Health Sex 2014;16:1169-80. [PubMed]

- Perez K, Gadgil M, Dizon DS. Sexual ramifications of medical illness. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2009;52:691-701. [PubMed]

- Me Corkle R, Grant M, Frank-Stromborg M, et al. eds. Cancer Nursing: A Comprehensive Textbook. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co., 1996.

- Park ER, Norris RL, Bober SL. Sexual health communication during cancer care: barriers and recommendations. Cancer J 2009;15:74-7. [PubMed]

- Bartula I, Sherman KA. Screening for sexual dysfunction in women diagnosed with breast cancer: systematic review and recommendations. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;141:173-85. [PubMed]

- Pinto AC, de Azambuja E. Improving quality of life after breast cancer: dealing with symptoms. Maturitas 2011;70:343-8. [PubMed]

- Perz J, Ussher JM, Gilbert E. Constructions of sex and intimacy after cancer: Q methodology study of people with cancer, their partners, and health professionals. BMC Cancer 2013;13:270. [PubMed]

- Goldfarb S, Mulhall J, Nelson C, et al. Sexual and reproductive health in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol 2013;40:726-44. [PubMed]

- Krychman ML, Katz A. Breast cancer and sexuality: multi-modal treatment options. J Sex Med 2012;9:5-13. [PubMed]

- Witherby S, Johnson J, Demers L, et al. Topical testosterone for breast cancer patients with vaginal atrophy related to aromatase inhibitors: a phase I/II study. Oncologist 2011;16:424-31. [PubMed]

- Barton DL, Wender DB, Sloan JA, et al. Randomized controlled trial to evaluate transdermal testosterone in female cancer survivors with decreased libido; North Central Cancer Treatment Group protocol N02C3. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:672-9. [PubMed]

- Le Ray I, Dell'Aniello S, Bonnetain F, et al. Local estrogen therapy and risk of breast cancer recurrence among hormone-treated patients: a nested case-control study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;135:603-9. [PubMed]

- Barton DL, Sloan JA, Shuster LT, et al. Impact of vaginal dehydroepiandosterone (DHEA) on vaginal symptoms in female breast cancer survivors: Trial N10C1 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol 2014;32:abstr 9507.

- Lee YK, Chung HH, Kim JW, et al. Vaginal pH-balanced gel for the control of atrophic vaginitis among breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:922-7. [PubMed]

- Loprinzi CL, Abu-Ghazaleh S, Sloan JA, et al. Phase III randomized double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy of a polycarbophil-based vaginal moisturizer in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:969-73. [PubMed]

- Goetsch MF, Lim JY, Caughey AB. Locating pain in breast cancer survivors experiencing dyspareunia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:1231-6. [PubMed]

- Goetsch MF, Lim JY, Caughey AB. A solution for dyspareunia in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123 Suppl 1:1S. [PubMed]

- Murina F, Bernorio R, Palmiotto R. The use of amielle vaginal trainers as adjuvant in the treatment of vestibulodynia: an observational multicentric study. Medscape J Med 2008;10:23. [PubMed]

- Juraskova I, Jarvis S, Mok K, et al. The acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy (phase I/II study) of the OVERcome (Olive Oil, Vaginal Exercise, and MoisturizeR) intervention to improve dyspareunia and alleviate sexual problems in women with breast cancer. J Sex Med 2013;10:2549-58. [PubMed]

- Duijts SF, van Beurden M, Oldenburg HS, et al. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and physical exercise in alleviating treatment-induced menopausal symptoms in patients with breast cancer: results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4124-33. [PubMed]