Psychosexual care in prostate cancer survivorship: a systematic review

Introduction

Meeting the needs is important (1). Psychosexual concerns comprise psychological, emotional and physical factors. Therefore a bio-psycho-social approach to understanding psychosexual concerns is helpful (2). This entails not only understanding the biology behind psychosexual concerns, but psychosocial reasons as to why psychosexual concerns occurred (2).

The prostate cancer (PC) ‘trifecta’ post therapy, denotes oncological, continence and erectile dysfunction (ED) outcomes. This varies accord to type of radical therapy. The majority of men after radical prostatectomy, never regain preoperative levels of erectile function without further treatment (2). This is compounded by an ageing physical function, worsening sexual function for men. Post radical therapy, there are side effects including reduced penile length, loss of desire, and loss of orgasmic satisfaction in the patient (2). A recent focus group study found that sexual problems were associated with a variety of common physical adverse effects such as cardiovascular comorbidity (3).

Patients with no psychosexual concerns pre-treatment can develop psychosexual concerns up to 14 months after radiotherapy (4). Patients receiving localised radiotherapy still had psychosexual concerns at 3 years following radiotherapy (47.6% at 1 year and 19% at 3 years) (5). Psychosexual concerns include lack of ejaculation in 2-56% (6-9), dissatisfaction with sexual intercourse in 25-60% of survivors (10,11), decreased libido in 8-53% (12) and decreased sexual desire in 12-58% of survivors (13,14).

The effect of brachytherapy on psychosexual concerns is also well documented (14). This is composed of several factors including pre-brachytherapy-implant potency, age, combination external-beam irradiation, radiation dose delivered to prostate gland, and bulb of the penis. Taken together, psychosexual concerns after seed implantation, affects 30-64% of men (15-19).

Furthermore with combination radiotherapy and brachytherapy, 63% of patients reported psychosexual concerns. Talcott and colleagues [2001] concluded that patients who had received combined brachytherapy and radiotherapy had a higher likelihood of psychosexual concerns (20).

Methods

Search strategy

The search strategy identified was all references relating to PC AND treatment AND ED treatment. Search terms used were as follows: (PC OR prostate neoplasms) AND (treatment) AND (ED). The selection criteria specified papers must be related to primary research only, in order to maintain the quality of the study. All secondary research apart from published systematic reviews or meta-analyses, were excluded.

The following databases were screened from 1984 to March 2014: CINAHL and MEDLINE (NHS Evidence), Cochrane, AMed, BNI, EMBASE, Health Business Elite, HMIC, PschINFO. In addition, searches using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords were conducted using Cochrane databases. Two UK-based experts in survivorship care were consulted to identify any additional studies.

Eligibility

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported primary research focusing on treatment of ED post PC treatment. Papers were included if published after 1984 and had to be in English. Studies that did not conform to this were excluded. Secondary research was excluded apart from systematic reviews or meta-analyses, as secondary research was deemed by the research panel (filtering the studies found), not to add to the selection criteria.

Abstracts were independently screened for eligibility by two reviewers and disagreements resolved through discussion or third party opinion. The agreement level was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa to test the intercoder reliability of this screening process (21). Cohens’ Kappa allows comparison of inter-rater reliability between papers using relative observed agreement. This also takes account of the comparison occurring by chance. For the first systematic review on treatment of ED, both reviewers agreed, all 19 papers were included. Kappas’ Cohen was calculated at 1.0 within a 95% confidence interval for both (21).

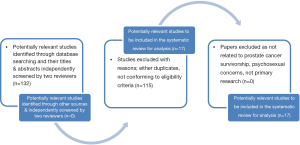

The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) and statement of main findings

ED post radical therapy for PC was the focus of all research. This is a very sizable group, not just in the UK but through the world. Due to the wide and varied nature of PC treatment as highlighted in the introduction, this group is often heterogeneous as a result narrative review was undertaken.

Data extraction and quality assessment of studies

Data extraction was piloted by the researcher and amended in consultation with the research team (author and two academic supervisors). Data collected included authors, year and country of publication, study aims, setting, intervention aims, number of participants, study design, intervention components and delivery methods, comparison groups and outcome measures, notes and follow-up questions for the authors. Studies were quality assessed using Mays et al. (22) for the action research and qualitative studies.

Systematic review findings

The searches identified 586 and 132 papers respectively (Figure 1 and Table 1). However, only 17 mapped to the search terms and eligibility criteria. The current systematic reviews were examined to gain further knowledge about the subject. Of the papers that did conform to search terms and eligibility criteria, relevant abstracts were identified and the full papers obtained (all of which were in English), to quality assure against criteria. There was considerable heterogeneity of design among the included studies therefore a narrative synthesis of the evidence was undertaken.

Full table

Characteristics of studies

Study designs varied, and were either cohort or qualitative. There were no randomised controlled trials. Studies were conducted by a range of members from the multidisciplinary team including specialist nurses, doctors and in addition, researchers.

Categorisation of papers

The papers within both systematic reviews can be categorised as follows.

Erectile dysfunction (ED)

Out of the systematic review on ED, only one focused on treatment post therapy (23). However, this demonstrated PDE5 inhibitors as part of ED, post PC treatment, erectile function is significantly improved.

Unmet needs and psychosexual concerns

Patients with psychosexual concerns will never have tried medications or devices to improve their erections (24). This is more common after brachytherapy or radiotherapy than after radical prostatectomy. This indicates a need for further research and management within this cohort (24).

A questionnaire (EORTC) was given to a sample of cancer survivors treated in Oxford who had pelvic radiotherapy up to 11 years previously for PC (25). Moderate to severe psychosexual impairment was common with 53% of mens’ ability to have a sexual relationship affected (26).

Symptom severity was significantly associated with poorer overall quality of life (QoL) and higher levels of depression. This study concluded it is imperative attention is paid to this subject, by secondary care, however, they did not specify any method for doing so.

Psychosexual impairment and adjuvant therapy

Adjuvant hormone therapy was associated with worse outcomes across multiple quality-of-life domains among patients receiving brachytherapy or radiotherapy. Patients in the brachytherapy group reported having persistent psychosexual impairment (27). Adverse effects of prostatectomy on sexual function were noted, despite nerve sparing. These changes influenced satisfaction with treatment outcomes among patients (27). This may indicate an older population of patient, who have further disease spread and so require more therapy. In contrast, whilst the treatment gives good oncological outcomes, there are significant psychosexual concerns, as demonstrated.

Psychosexual concerns and time since procedure

Time since prostatectomy had a negative effect on psychosexual impairment. Elderly men at follow-up experienced worse psychosexual impairment. Higher stage PC also negatively psychosexual impairment. Older age at follow up and higher pathological stage were associated with worse QoL outcomes after radical treatment. These both re-iterate the above points.

Quality of life (QoL)

For male patients, QoL resulting from psychosexual impairment, is the primary area of concern (28). Patients involved very often have discomfort with sexual side effects of their cancer treatment, including decreased sexual desire and satisfaction. It was also recognised patients and their spouses may have differing perceptions regarding QoL and the impact of sexual functioning on survivorship (28). This emphasises the need for further research towards psychosexual concerns.

Kimura et al. 2013b (29) examined psychosexual impairment and found post-operatively this is neglected. They also found patients with psychosexual impairment, despite having operative intervention were more likely to be old and had a higher clinical T stage with none non-nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy conducted, with extra capsular extension may not necessarily enquire into medical therapy post operatively (29). This again found psychosexual impairment affected QoL (30). Psychosexual impairment significantly affects all three treatment groups. These results may guide decision making for treatment selection and clinical management of patients with health-related quality-of-life impairments after treatment for localised PC (31).

Fifty percent of the study group had used PDE5 inhibitors after treatment start. This cohort again reported a high level of psychosexual impairment post treatment. Another study demonstrated severe perceived consequences of treatment were associated with poorer emotional well-being, especially in those with greater life stress. Interventions that target distortions in illness perceptions may enhance emotional adjustment among the most distressed PC survivors (32).

Few men regretted having RP at 1 year after treatment, even though some QoL functions and domains were significantly affected (33). Ongoing assessment of the effect of surgical treatment on sexual function, sexuality and masculinity certainly deserves further exploration with this group of cancer survivors.

A counselling intervention demonstrating improvement in psychosexual concerns and increased utilization of medical therapy (34). However, modifications are needed in future randomised trials to reduce the rate of premature termination and to improve long-term maintenance of gains.

Quality assessment of studies

Qualitative studies were assessed using (22). All studies (n=17) described withdrawal and dropout rates. They also presented clear and appropriate methods and outcomes. Blinding was not applicable in any study, as there were no randomised clinical trials. The flow of participants was represented in a ‘consort style’ diagram in 17 studies. Allocation concealments of participants were not appropriate. Greater than 80% of participants did provide follow-up data of interest. No studies had sample size calculated statistically. An adequate summary of results for each study outcome was provided in all studies. Sampling was explicitly defined, as was the method of recruitment and intervention.

For the qualitative studies, they further contributed to understanding of the topic. Appropriate methods were chosen with a literature review present. These studies also contribute to development of knowledge of this subject. The sample was appropriate, with a clear description of data collection which was appropriately managed. Validity criteria were present. The analysis of each was clearly described with adequate discussion. Findings were confirmed in the study, excerpts were transcribed. There was appropriate discussion including an alternative explanation and results of each study are applicable to this area of research.

Methods for follow-up

Global QoL was measured by (31), using short form 12, as a snapshot in time. Traegar et al. (32), on the other hand used the UCLA on the other hand, used the UCLA expanded PC index. Davison et al. (33) used the EORTC C30 questionnaire to determine QoL. Clark and Talcott (35) looked at sexual confidence, sexual self-esteem and masculine self-esteem as part of their questionnaires. Canada et al. (36) used four sessions of counselling as part of their follow-up.

Strengths and limitations

The search criteria of this review included prostate cancer and psychosexual impairment. This was focused on psychosexual concerns in PC survivors. Studies were assessed for both methodological quality and strength of psychosexual care. The review is limited by the different methodological studies. It was a relatively heterogeneous population, indicating the conclusions published are valid. In addition, as only published studies were included, some relevant ongoing studies may have been excluded. This again will impact on our overall conclusions.

Findings in relation to other survivorship and psychosexual studies

Cleary and Hegarty (37) examined at sexual self-concept, sexual relationships, and sexual functioning in women. They highlight sexual relationships focus on communication and intimacy, with emphasis on desire, arousal and excitement. Whilst this study was conducted in the opposite gender, it still teaches us about psychosexual concerns. Yet, in clinical practice, this is not done. Factors positively associated improvement in psychosexual concerns include age, preoperative sexual and overall physical function and extent of treatment (38). After treatment prompt psychosexual rehabilitation has been shown to have good effect (39).

Psychosexual concerns impact greatly on this cohort with decreased sexual function as the cause of disease-specific distress in this population (40). There are significant psychological implications within this group due to the nature of the treatment involved (41). Even though patients may return to a baseline level of sexual function, they continue to report psychosexual concerns (42). It is recommended that men undergoing this seek appropriate advice and treatment (43). There is evidence to show that psychosexual care can aid recovery.

Psychosexual concerns are represented as a bio-psychosocial model, requiring the input from the MDT team (44). Social support and relationship functioning are important with regards to this.

Current systematic reviews relating to psychosexual care

Psychosexual care

Current systematic reviews on psychosexual concerns cover a range of topics. The most important findings are as follows.

Some tend to focus on aetiology of psychosexual concerns post treatment (45). Whereas others tend to review psychosocial interventions that can be used to improve communication within this cohort (43). Other reviews look at QoL across several cancer types. Specifically for PC, it was found that patients did have psychosexual concerns post treatment that were unaddressed (46). Others review literature on rehabilitation, concluding there are no consensus guidelines regarding this (47). Goldfarb et al., examined sexual health in cancer survivors, and found early intervention (was required post therapy, with fertility preservation in the young (48). Latini et al. went one step further (49). They identified psychosexual interventions in studies as a primary goal had better results.

Furthermore, they identified that this needed to be personalised and tailored.

Statement of main findings

PC survivorship was the focus of research in all studies. This is a very sizable group, not just in the UK but through the world. This systematic review highlighted the following key components of Survivorship Care with ED, acute and chronic medical co-morbidity and side effects of therapy as the greatest concerns. Psychosexual care was an unmet need in the majority of studies found in the literature review. The number of patients with unmet need is a sizable group according to the literature, not just in the UK but globally.

Conclusions

One of the greatest concerns post radical therapy for PC, is psychosexual care. Whilst there are many tools to assess and treat psychosexual concerns, they are not often used. Furthermore, guidance is needed, with regards to psychosexual care in the PC survivorship cohort.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Persad for being a really brilliant academic mentor.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Wittmann DA, Monties JE, He C, et al. A pilot study of the effect of a one-day retreat on sexuality on prostate cancer survivors’ and partners’ information awareness, help-seeking attitudes, sexual communication and sexual activity. J Sex Med 2013;10:143.

- Bober SL, Sanchez Varela V. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: Challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3712-9. [PubMed]

- Flynn KE, Jeffery DD, Keefe FJ, et al. Sexual functioning along the cancer continuum: Focus group results from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Psychooncology 2011;20:378-86. [PubMed]

- Zelefsky MJ, Eid JF. Elucidating the etiology of erectile dysfunction after definitive therapy for prostatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998;40:129-33. [PubMed]

- Namiki S, Arai Y. Health-related quality of life in men with localized prostate cancer: Review Article. Int J Urol 2010;17:125-38. [PubMed]

- Schwartz K, Bunner S, Bearer R, et al. Complications from treatment for prostate carcinoma among men in the Detroit area. Cancer 2002;95:82-9. [PubMed]

- Tomić R. Some effects of orchiectomy, oestrogen treatment and radiation therapy in patients with prostatic carcinoma. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 1983;77:1-37. [PubMed]

- McGowan DG. Radiation therapy in the management of localized carcinoma of the prostate. A preliminary report. Cancer 1977;39:98-103. [PubMed]

- Helgason AR, Fredrikson M, Adolfsson J, et al. Decreased sexual capacity after external radiation therapy for prostate cancer impairs quality of life. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995;32:33-9. [PubMed]

- Joly F, Brune D, Couette JE, et al. Health-related quality of life and sequelae in patients treated with brachytherapy and external beam irradiation for localized prostate cancer. Ann Oncol 1998;9:751-7. [PubMed]

- van Heeringen C, De Schryver A, Verbeek E. Sexual function disorders after local radiotherapy for carcinoma of the prostate. Radiother Oncol 1988;13:47-52. [PubMed]

- Beckendorf V, Hay M, Rozan R, et al. Changes in sexual function after radiotherapy treatment of prostate cancer. Br J Urol 1996;77:118-23. [PubMed]

- Caffo O, Fellin G, Graffer U, et al. Assessment of quality of life after radical radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Br J Urol 1996;78:557-63. [PubMed]

- D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 1998;280:969-74. [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Ortiz RF, Broderick GA, Rovner ES, et al. Erectile function and quality of life after interstitial radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Impot Res 2000;12 Suppl 3:S18-24. [PubMed]

- Matzkin H, Chen J, German L, et al. Comparison between preoperative and real-time intraoperative planning 125I permanent prostate brachytherapy: long-term clinical biochemical outcome. Radiat Oncol 2013;8:288. [PubMed]

- Stock RG, Kao J, Stone NN. Penile erectile function after permanent radioactive seed implantation for treatment of prostate cancer. J Urol 2001;165:436-9. [PubMed]

- Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, et al. Erectile function after prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;62:437-47. [PubMed]

- Zelefsky MJ, Wallner KE, Ling CC, et al. Comparison of the ear outcome and morbidity of three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy versus transperineal permanent iodine-125 implantation for early-stage prostatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:517-22. [PubMed]

- Talcott JA, Clark JA, Stark PC, et al. Long-term treatment related complications of brachytherapy for early prostate cancer: A survey of patients previously treated. J Urol 2001;166:494-9. [PubMed]

- Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968;70:213-20. [PubMed]

- Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:6-20. [PubMed]

- Eardley I, Mirone V, Montorsi F, et al. An open-label, multicentre, randomized, crossover study comparing sildenafil citrate and tadalafil for treating erectile dysfunction in men naive to phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor therapy. BJU Int 2005;96:1323-32. [PubMed]

- Miller DC, Wei JT, Dunn RL, et al. Use of medications or devices for erectile dysfunction among long-term prostate cancer treatment survivors: Potential influence of sexual motivation and/or indifference. Urology 2006;68:166-71. [PubMed]

- Adams E, Boulton MG, Horne A, et al. The Effects of Pelvic Radiotherapy on Cancer Survivors: Symptom Profile, Psychological Morbidity and Quality of Life. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2014;26:10-7. [PubMed]

- Adams MJ, Collins VR, Dunne MP, et al. Male reproductive health disorders among aboriginal and torres strait islander men: A hidden problem? Med J Aust 2013;198:33-8. [PubMed]

- Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1250-61. [PubMed]

- Rivers BM, August EM, Gwede CK, et al. Psychosocial issues related to sexual functioning among African-American prostate cancer survivors and their spouses. Psychooncology 2011;20:106-10. [PubMed]

- Kimura M, Banez LL, Polascik TJ, et al. Sexual bother and function after radical prostatectomy: predictors of sexual bother recovery in men despite persistent post-operative sexual dysfunction. Andrology 2013;1:256-61. [PubMed]

- Gore JL, Kwan L, Lee SP, et al. Survivorship beyond convalescence: 48-month quality-of-life outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:888-92. [PubMed]

- Kyrdalen AE, Dahl AA, Hernes E, et al. A national study of adverse effects and global quality of life among candidates for curative treatment for prostate cancer. BJU Int 2013;111:221-32. [PubMed]

- Traeger L, Penedo FJ, Gonzalez JS, et al. Illness perceptions and emotional well-being in men treated for localized prostate cancer. J Psychosom Res 2009;67:389-97. [PubMed]

- Davison BJ, So AI, Goldenberg SL. Quality of life, sexual function and decisional regret at 1 year after surgical treatment for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int 2007;100:780-5. [PubMed]

- Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, et al. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2005;104:2689-700. [PubMed]

- Clark JA, Talcott JA. Confidence and uncertainty long after initial treatment for early prostate cancer: survivors' views of cancer control and the treatment decisions they made. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4457-63. [PubMed]

- Canada AL, Murphy PE, Fitchett G, et al. A 3-factor model for the FACIT-Sp. Psychooncology 2008;17:908-16. [PubMed]

- Cleary V, Hegarty J. Understanding sexuality in women with gynaecological cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2011;15:38-45. [PubMed]

- Harris CR, Punnen S, Carroll PR. Men with low preoperative sexual function may benefit from nerve sparing radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2013;190:981-6. [PubMed]

- Namiki S, Ishidoya S, Ito A, et al. The impact of sexual desire on sexual health related quality of life following radical prostatectomy: a 5-year follow up study in Japan. Eur Urol Suppl 2012;11:e671.

- Parker PA, Pettaway CA, Babaian RJ, et al. The effects of a presurgical stress management intervention for men with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3169-76. [PubMed]

- Nelson CJ, Kenowitz J. Communication and Intimacy-Enhancing Interventions for Men Diagnosed with Prostate Cancer and Their Partners. J Sex Med 2013;10:127-32. [PubMed]

- Zaider T, Manne S, Nelson C, et al. Loss of masculine identity, marital affection, and sexual bother in men with localized prostate cancer. J Sex Med 2012;9:2724-32. [PubMed]

- Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Roth AJ. The Association Between Erectile Dysfunction and Depressive Symptoms in Men Treated for Prostate Cancer. J Sex Med 2011;8:560-6. [PubMed]

- Peltier A, Van Velthoven R, Roumeguere T. Current management of erectile dysfunction after cancer treatment. Curr Opin Oncol 2009;21:303-9. [PubMed]

- Akbal C, Tinay I, Simsek F, et al. Erectile dysfunction following radiotherapy and brachytherapy for prostate cancer: pathophysiology, prevention and treatment. Int Urol Nephrol 2008;40:355-63. [PubMed]

- Bloom JR, Petersen DM, Kang SH. Multi-dimensional quality of life among long-term (5+ years) adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2007;16:691-706. [PubMed]

- Chung E, Brock G. Sexual Rehabilitation and Cancer Survivorship: A State of Art Review of Current Literature and Management Strategies in Male Sexual Dysfunction Among Prostate Cancer Survivors. J Sex Med 2013;10:102-11. [PubMed]

- Goldfarb S, Mulhall J, Nelson C, et al. Sexual and reproductive health in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol 2013;40:726-44. [PubMed]

- Latini DM, Hart SL, Coon DW, et al. Sexual rehabilitation after localized prostate cancer. Current interventions and future directions. Cancer J 2009;15:34-40. [PubMed]