Efficacy of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in patients with erectile dysfunction after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

One in six men had been diagnosed with prostate cancer (PCa) in their lifetime, making PCa the most common type of cancer among men in Western countries (1,2). Approximately 94% of patients are diagnosed with localized PCa and thus need to undergo nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy (NSRP) (2,3). The number of radical prostatectomy (RP) operation has been rapidly increasing over years, and the age of patients seeking for this treatment has also increased correspondingly (4).

Despite the fact that NSRP is usually performed to promote the functional outcomes, such as erectile function, erectile dysfunction (ED) results frequently after the procedure. Postoperative ED has been reported in 15–18% of patients who undergo NSRP (5,6). It is a condition that can potentially take a toll on the patients’ everyday life (4). Therefore, if postoperative ED is less likely to occur, more patients will decide to receive NSRP (7). Various factors affect the development and severity of postoperative ED; these include patient age, preoperative potency, stage of the tumor, and surgeon’s experience (8-12). Postoperative ED can also cause vascular damage, neural injury, and smooth muscle damage (13,14).

The emergence of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDE5-Is) has innovated ED treatment with a success rate of approximately 60–70% (15,16). PDE5-Is are the most common treatment agent for postoperative ED. The efficacy and adverse effects of PDE5-Is have been reported; however, there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate the optimal use of PDE5-Is for penile rehabilitation. Several errors were found in meta-analyses and systematic reviews that have been performed to assess the efficacy and adverse effects of PDE5-Is (17-19). Therefore, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy and safety of PDE5-Is in patients with ED after NSRP.

We present the following article in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting checklist (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-21-881/rc).

Methods

We performed a systematic review to identify publications evaluating the efficacy and safety of PDE5-Is in patients with ED after NSRP. This systematic review and protocol was registered in PROSPERO database: CRD42020193371. There was no modifications to the protocol during the study process. This study was conducted in accordance with PRISMA and Meta-Analyses and Cochrane Review Methods (20).

Data and literature sources

We used the OVID platform to search for relevant literature in the following databases: EMBASE (from 1974), OVID MEDLINE (R) 1946 up to the present (OVID platform), OVID MEDLINE (R) Daily and MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (OVID platform), and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (OVID platform) from inauguration to July 2020. In addition, a literature search of the Web of Science was conducted to find all relevant studies. We also manually searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov for additional unpublished and published studies. The main keywords used were ED, nerve-sparing prostatectomy, PDE5-I, and randomized controlled trial.

Study selection

All searched studies were independently selected by two reviewers according to predefined selection criteria. When disagreements occurred on primary study selection, a third reviewer arbitrated them. The predefined selection criteria in our meta-analysis were as follows: (I) randomized controlled trial published in any international journal in English language, (II) adult patients undergoing treatment with PDE5-Is for ED after nerve-sparing prostatectomy, (III) studies comparing the effects of PDE5-Is with those of placebo regardless of the treatment regimen, and (IV) the International Index of Erectile Function—Erectile Function (IIEF) domain score as the primary outcome, which was used for evaluating postoperative erectile function rehabilitation. In these studies, the number of patients who achieved erectile function recovery after PDE5-I treatment was also measured. The secondary outcomes were positive responses to Sexual Encounter Profile (SEP) questions 2 and 3, which were included for additional assessment of postoperative erectile function rehabilitation and the incidence of adverse events after PDE5-I treatment. The outcome variables were mean differences (MDs) or the incidence of events between the groups at designated times.

Data extraction

The two reviewers independently extracted data through a prespecified data extraction form, and the third reviewer reviewed the extracted data. The following variables were extracted: (I) patient characteristics and number of patients, (II) means and standard deviations or incidence of events; (III) administration and dosage of detailed interventions; (IV) treatment time; and (V) incidence of adverse events after each intervention. When the abovementioned variables were not mentioned in the study, the data were requested via email.

Assessment of methodological quality

The risks of bias in the studies were independently estimated by two reviewers using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. This tool evaluates the quality of randomized controlled studies by reviewing the generation of random sequences, blinding of participants, assessment of outcomes, allocation concealment, incompleteness in outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other possible sources of risk of bias.

Quality of evidence

The quality of the evidence of the outcome data was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (20). The two reviewers independently evaluated the quality of each outcome. The five categories of GRADE quality assessment were limitations of design, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. “Summary of findings” tables were presented using a GRADE profiler (GRADEpro) and included the following outcomes: (I) IIEF domain score, (II) erectile function recovery event, (III) improvement in the response to SEP question 2, (IV) improvement in the response to SEP question 3, (V) incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), (VI) incidence of headache, and (VII) incidence of flushing.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were presented as MDs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and were analyzed using weighted MDs and the generic inverse variance method. Binary outcomes, such as the incidence of adverse events, were analyzed by comparing odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Heterogeneity between studies was evaluated using the χ2 test and I2statistics (21). I2values of >50% and P values of <0.10 in the χ2 test were regarded as statistically significant. When significant clinical or statistical heterogeneity was found, random-effects models were applied.

A subgroup analysis was conducted according to the regimen of PDE5-I treatment, such as daily use and on-demand use. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of risk of bias on our estimates. When the study had 3 or more the unclear or high risk of bias, we excluded from analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager Software (RevMan version 5.4.). Publication bias was evaluated by the funnel plots in the meta-analysis.

Results

Identification of the studies

Initial searches of the databases identified 597 publications. After removal of 314 duplicated articles, 283 articles were further excluded after reviewing their titles and abstracts. The full text of the 28 remaining articles was obtained for scrutiny; of these, 14 were excluded because they were abstracts (n=4); they used a different study design (n=2); the study design was not randomized (n=4); or the same data were reported (n=4). Thus, 14 studies involving 2,822 participants were finally included in this meta-analysis (Figure 1) (22-35).

Study characteristics and patient populations

Seven studies were performed in multiple centers and the other studies in three countries: Germany (n=3), Italy (n=2), and Turkey (n=2) between 2003 and 2015. Of these, four studies evaluated the efficacy of PDE5-Is after unilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy (UNSRP) or bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy (BNSRP) (28,31,32,35) and nine studies after BNSRP (22-24,26,27,29,30,33,34). The characteristics of the studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Study | Year | Country/region | Intervention | Control | Sample size | Treatment period | Surgical approach | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | |||||||

| Aydogdu et al. (26) | 2011 | Turkey | Tadalafil 20 mg/day | Placebo | 32 | 33 | 6 months | BNSRP |

| Bannowsky et al. (31) | 2008 | Germany | Sildenafil 25 mg/day | Placebo | 23 | 18 | 52 weeks | UNSRP |

| BNSRP | ||||||||

| Bannowsky et al. (28) | 2010 | Germany | Sildenafil 25 mg/day | Placebo | 23 | 18 | 78 weeks | UNSRP |

| BNSRP | ||||||||

| Bannowsky et al. A (25) | 2012 | Germany | Vardenafil 5 mg/day | Placebo | 12 | 12 | 12 months | UNSRP |

| Bannowsky et al. B (25) | Vardenafil 10 mg/day | 12 | ||||||

| Brock et al. A (35) | 2003 | United States and Canada | Vardenafil 10 mg on demand | Placebo | 140 | 140 | 3 months | UNSRP |

| Brock et al. B (35) | Vardenafil 20 mg on demand | 147 | BNSRP | |||||

| Canat et al. A (22) | 2015 | Turkey | Tadalafil 20 mg three times/week | Placebo | 38 | 34 | 12 months | BNSRP |

| Canat et al. B (22) | Tadalafil 20 mg on demand | 40 | ||||||

| Cavallini et al. (33) | 2005 | Italy | Sildenafil 100 mg on demand | Placebo | 35 | 29 | 4 months | BNSRP |

| Montorsi et al. (34) | 2004 | Canada, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, United States, and United Kingdom | Tadalafil 20 mg on demand | Placebo | 201 | 102 | 3 months | BNSRP |

| Montorsi et al. A (30) | 2008 | Europe, United States, Canada, and South Africa | Vardenafil 10 mg/day | Placebo | 137 | 145 | 9 months | BNSRP |

| Montorsi et al. B (30) | Vardenafil 10 mg (5 to 20 mg) on demand | 141 | ||||||

| Montorsi et al. A (23) | 2014 | Nine European countries and Canada | Tadalafil 5 mg/day | Placebo | 138 | 141 | 9 months | BNSRP |

| Montorsi et al. B (23) | Tadalafil 20 mg on demand | 143 | ||||||

| Mulhall et al. A (24) | 2013 | 53 sites in the United States | Avanafil 100 mg on demand | Placebo | 99 | 100 | 3 months | BNSRP |

| Mulhall et al. B (24) | Avanafil 200 mg on demand | 99 | ||||||

| Nehra et al. A (32) | 2005 | United States and Canada | Vardenafil 10 mg on demand | Placebo | 140 | 140 | 3 months | UNSRP |

| Nehra et al. B (32) | Vardenafil 20 mg on demand | 147 | BNSRP | |||||

| Pace et al. (27) | 2010 | Italy | Sildenafil 50 or 100 mg/day | Placebo | 20 | 20 | 6 months | BNSRP |

| Padma-Nathan et al. A (29) | 2008 | North America, France, Belgium, and Australia | Sildenafil 50 mg/day | Placebo | 40 | 42 | 9 months | BNSRP |

| Padma-Nathan et al. B (29) | Sildenafil 100 mg/day | 41 | ||||||

BNSRP, bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy; UNSRP, unilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy.

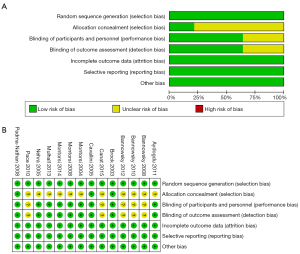

Quality of the included studies

Although all 14 studies used a random method, most studies did not describe detailed allocation concealment methods. The risks of blinding of participants and outcome assessment were unclear in five studies. The risks of selective reporting, incomplete outcome data, and other bias were low. Risk of bias graphs and summaries are presented in (Figure 2A,2B).

Efficacy

IIEF domain score

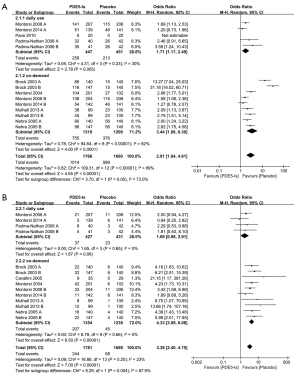

Our meta-analysis found significant improvements in the IIEF domain score after PDE5-I treatment (MD =4.93; 95% CI: 4.14–5.71; P<0.00001; I2=53%) (Figure 3A). A subgroup analysis was conducted according to the regimen of PDE5-I treatment. The subgroup analysis revealed significantly improved IIEF domain scores for both daily use (MD =4.68; 95% CI: 3.89–5.46; P<0.00001; I2=0%) and on-demand use (MD =4.98; 95% CI: 3.57–6.39; P=0.0003; I2=74%).

Erectile function recovery after PDE5-I treatment was determined at an IIEF domain score of >25 in four studies (26,27,30,34) and IIEF domain score of ≥22 in one study (23). The incidence of erectile function recovery events was also higher after PDE5-I treatment (OR =2.06; 95% CI: 1.45–2.94; P<0.0001; I2=42%) (Figure 3B). The subgroup analysis revealed that the incidence of these events was significantly higher for daily use (OR =1.68; 95% CI: 1.15–2.45; P=0.007; I2=0%) and on-demand use of PDE5-Is (OR =2.76; 95% CI: 1.34–5.69; P=0.006; I2=70%).

Response to the SEP questions

The rate of positive response to SEP question 2 was significantly higher after PDE5-I treatment (OR =2.27; 95% CI: 1.80–2.86; P<0.00001; I2=23%) (Figure 4A). The subgroup analysis revealed a significantly higher positive response rate for on-demand use of PDE5-Is (OR =2.39; 95% CI: 1.81–3.15; P<0.00001; I2=34%).

Meanwhile, the rate of positive response to SEP question 3 was also significantly higher after PDE5-I treatment (OR =2.78; 95% CI: 1.97–3.91; P<0.00001; I2=64%) (Figure 4B). The subgroup analysis also revealed a higher positive response rate to SEP question 3 for daily use (OR =1.73; 95% CI: 1.19–2.50; P=0.004; I2=0%) and on-demand use of PDE5-Is (OR =3.32; 95% CI: 2.15–5.12; P<0.00001; I2=68%).

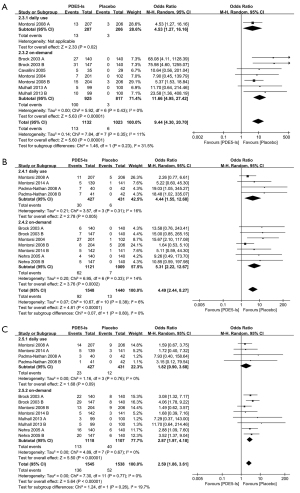

Safety

The incidence of TEAEs was reported in eight studies. In our analysis, we found a higher incidence of TEAEs after PDE5-I treatment than after placebo treatment (OR =2.91; 95% CI: 1.84–4.61; P<0.00001; I2=89%) (Figure 5A). In the subgroup analysis, the OR for the incidence of TEAEs for on-demand PDE5-I treatment (OR =3.44; 95% CI: 1.88–6.30; P<0.00001; I2=92%) was higher than that for daily PDE5-I treatment (OR =1.71; 95% CI: 1.17–2.49; P=0.005; I2=30%). However, clinically serious adverse events related to the study drug were not reported in the included studies.

In terms of headache, we found a significantly higher incidence in the patients who received PDE5-I treatment (OR =3.38; 95% CI: 2.40–4.75; P<0.00001; I2=23%) (Figure 5B). The subgroup analysis revealed that the incidence of headache was significantly higher for on-demand PDE5-I treatment (OR =4.33; 95% CI: 3.09–6.08; P<0.00001; I2=0%) than for daily PDE5-I treatment (OR =1.69; 95% CI: 0.98–2.91; P=0.06; I2=0%).

In terms of flushing (OR =9.44; 95% CI: 4.30–20.70; P<0.00001; I2=11%) (Figure 6A), dyspepsia (OR =4.49; 95% CI: 2.44–8.27; P<0.00001; I2=6%) (Figure 6B), and nasopharyngitis (OR =2.59; 95% CI: 1.97–4.18; P<0.00001; I2=0%), we found a significantly higher incidence in the patients who received PDE5-I treatment (Figure 6C).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the influence of risk of bias on our estimates. Five studies (16,19,21,22,25) had unclear risk of bias in three components. These studies were included in the analysis of the improvements in IIEF score, the incidence of erectile function recovery events, and the incidence of TEAEs. The sensitivity analysis revealed that the risk of bias did not alter the outcome of this meta-analysis (Table 2).

Table 2

| Outcome | Studies, n | Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, n | Control patients, n | OR or MD | 95% CI | P value for effect | P value for heterogeneity | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The improvements in IIEF score | ||||||||

| Total studies | 11 (22-25,27-29,31,33,34,35) | 1,143 | 1,004 | 4.93 | 4.14 to 5.71 | <0.00001 | 0.005 | 53 |

| Including only studies with low risk of bias | 6 (23,24,29,33-35) | 973 | 856 | 4.99 | 3.78 to 6.20 | <0.00001 | 0.002 | 65 |

| The incidence of erectile function recovery events | ||||||||

| Total studies | 5 (23,26,27,30,34) | 807 | 732 | 2.06 | 1.45 to 2.94 | <0.0001 | 0.11 | 42 |

| Including only studies with low risk of bias | 4 (23,26,30,34) | 787 | 712 | 2.07 | 1.40 to 3.05 | 0.0002 | 0.07 | 52 |

| The incidence of TEAEs | ||||||||

| Total studies | 8 (23,24,27,29,30,32,34,35) | 1,766 | 1,660 | 2.91 | 1.84 to 4.61 | <0.00001 | <0.00001 | 89 |

| Including only studies with low risk of bias | 7 (23,24,29,30,32,34,35) | 1,746 | 1,640 | 2.91 | 1.84 to 4.61 | <0.00001 | <0.00001 | 89 |

n, the number of cases; OR, odds ratio; MD, mean difference; CI, confidence interval; IIEF, International Index of Erectile Function—Erectile Function; TEAEs, treatment-emergent adverse events.

Quality of evidence

The quality of the evidence of the outcome data, which was assessed using the GRADE approach, is presented in (Table 3). Herein, the quality ranged from low to moderate. Inconsistency problems were detected in all outcomes and imprecision problems in most outcomes. As the statistical power was low owing to the number of included studies (≤10), publication bias was not assessed (20).

Table 3

| Outcomes | Studies, n | Patients, n | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Quality of evidence (GRADE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDE5-Is | Placebo | Risk with PDE5-Is | Risk with placebo | |||||

| IIEF domain score | 11 RCTs | 1,143 | 1,004 | The IIEF domain score was 4.93 higher (from 4.14 higher to 5.71 higher) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ | |||

| MODERATE1 | ||||||||

| Recovery events in relation to the IIEF domain score | 5 RCTs | 252/807 (31.2%) | 143/732 (19.5%) | 138 more per 1,000 (from 65 more to 221 more) | 195 per 1,000 | OR =2.06 (1.45 to 2.94) | ⨁⨁◯◯ | |

| LOW1,2 | ||||||||

| Response to SEP question 2 | 7 RCTs | 447/987 (45.3%) | 233/886 (26.3%) | 185 more per 1,000 (from 128 more to 242 more) | 263 per 1,000 | OR =2.27 (1.80 to 2.86) | ⨁⨁◯◯ | |

| LOW1,2 | ||||||||

| Response to SEP question 3 | 7 RCTs | 469/1,301 (36.0%) | 221/1,209 (18.3%) | 201 more per 1,000 (from 123 more to 284 more) | 183 per 1,000 | OR =2.78 (1.97 to 3.91) | ⨁⨁◯◯ | |

| LOW1,2 | ||||||||

| Incidence of TEAEs | 8 RCTs | 1,014/1,766 (57.4%) | 376/1,209 (31.1%) | 157 more per 1,000 (from 110 more to 204 more) | 311 per 1,000 | OR =1.95 (1.61 to 2.35) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ | |

| MODERATE1 | ||||||||

| Incidence of headache | 8 RCTs | 207/1,781 (11.6%) | 68/1,669 (4.1%) | 85 more per 1,000 (from 52 more to 127 more) | 41 per 1,000 | OR =3.38 (2.40 to 4.75) | ⨁⨁◯◯ | |

| LOW1,2 | ||||||||

The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) was based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). 1, downgraded by one level owing to inconsistency; 2, downgraded by one level owing to imprecision. GRADE Working Group quality of evidence. High quality, we are very confident that the true effect lies close to the estimate of the effect; Moderate quality, we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect; however, there is a possibility that it is substantially different; Low quality, our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect; Very low quality, we have very limited confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; n, the number of cases; PDE5-I, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor; CI, confidence interval; IIEF, International Index of Erectile Function—Erectile Function; RCT, randomized controlled trial; OR, odds ratio; SEP, Sexual Encounter Profile; TEAEs, treatment-emergent adverse events.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis and systematic review of the efficacy and safety of PDE5-Is demonstrated the feasibility of this treatment as penile rehabilitation after NSRP. The use of PDE5-Is improved the total IIEF domain score, erectile function recovery, and positive response rate to each SEP question. However, some adverse effects were noted, including headache, flushing, and dyspepsia.

Recovery of postoperative ED takes up to 4 years, and approximately 20–80% of patients recover their erectile function (16). Thermal damage to the cavernous nerve can result in permanent loss of potency after RP, and vascular damage in the accessory pudendal arteries can occur. Moreover, traction during RP can be damaged, resulting in conditions, such as neurapraxia. Neurapraxia can consequently result in structural changes in the endothelium and smooth muscle during RP (36).

New insights into the pathophysiology of postoperative ED led to the development of a rehabilitation strategy defined as the use of any drug or device in patients who have undergone RP to maximize the recovery of erectile function. The efficacy and adverse effects of PDE5-Is as penile rehabilitation were previously evaluated in meta-analyses and systematic reviews (17-19). However, concerns on the methodological quality have been raised in these reports. In these previous reports, errors in the data entered could be found, which has led to problems regarding the methodological query. In the age of evidence-based medicine, systematic review plays an important role in clinical decision making (37). In this situation, errors in the previous systematic reviews gave clinicians wrong information for decision making. These analyses were performed by entering the intention-to-treat population as the total number, and not the complete study population, or by entering the value of the score change as the value of the score. Additionally, there were cases in which the total population value and standard deviation value were incorrectly entered into the study data. Moreover, a retrospective study was included in a previous meta-analysis. Although the research subject of previous studies was the same as that of our study, our systematic review analyzed the results of 14 studies compared to only 6 to 8 studies included in the former. In addition, the quality of the evidence of the outcome data was evaluated using the GRADE approach in this systematic review. Taken together, our analysis provides a more accurate and reliable basis for penile rehabilitation, including the latest findings.

A part of the physiological process is the release of nitrous oxide (NO) in the blood vessels of the corpus cavernosum by sexual stimulation. NO activates the guanylate cyclase enzyme, which increases the number of annular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). cGMP relaxes the catholic blood vessels, increasing blood flow and consequently evoking it. PDE5-I decomposition of cGMPs by phosphodiesterase type 5 increases the blood flow of the penis during sexual stimulation. Owing to this mechanism of action, PDE5-Is work only when there is sexual stimulation. Our analysis also demonstrated the superior efficacy of PDE5-Is with the improvements observed in the IIEF domain score, erectile function recovery, and positive response rate to SEP questions 2 and 3.

A subgroup analysis was conducted to assess the effects of the regimen of PDE5-I treatment, i.e., daily use and on-demand use. We found that on-demand use of PDE5-Is was more efficient than daily use of PDE5-Is. The pharmacokinetics of PDE5-Is showed a steady state after 5 days of daily use, with a total plasma concentration of 55 ng/mL achieving a reasonable drug dynamics goal, indicating maintenance of these concentrations over a 24-hour administration interval (18,38). In terms of side effects, daily use yielded a lower incidence than did on-demand use, and a fundamental change in the plasma concentration was expected. Considering these factors, the optimal administration methods can be considered depending on the degree of response.

In terms of safety, most studies have raised concerns on cardiovascular safety, although some studies have reported that PDE5-Is can have beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system (39-43). Because cardiovascular safety is directly linked to survival, it should be considered differently from other factors, even if it is less frequent. Although the total incidence of adverse events associated with PDE5-I administration was higher than that with placebo treatment, no serious cardiovascular adverse events were reported in our analysis. Our subgroup analysis showed that daily use of PDE5-Is had fewer side effects than on-demand use of PDE5-Is. A well-organized large-scale study is needed to confirm the difference in the effects of the regimen of PDE5-I treatment.

Nandipati et al. (44) reported the effectiveness of combination therapy in penile rehabilitation and reported that combination therapy of intra-cavenosal injection and PDE5-I were effective for ED. According to reporting by Deng et al. (45), the combination therapy of PDE5-I and vacuum erection device had a synergistic effect in penile rehabilitation. Although these studies were not included in this analysis because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, it should be considered that PDE5-I based combination therapy is effective in penile rehabilitation.

Limitations

First, clinical heterogeneity among the studies was observed. The type of treatment drug, drug dose, frequency of drug administration, and treatment period varied among the studies. Because of this heterogeneity, all outcomes were evaluated using a random-effects model. To eliminate heterogeneity in the frequency of drug administration, we conducted a subgroup analysis. Consequently, this heterogeneity did not affect the results. Second, the GRADE assessments demonstrated that the quality of the evidence of some outcome data was low. These outcome assessments revealed problems of imprecision and inconsistency. Lastly, only randomized controlled trials were included in this meta-analysis to increase the reliability of the assessments. It is possible that the incidence of TEAEs is low because the predetermined exclusion criteria used for the randomized controlled trials excluded uncommon clinical situations. Third, a patient’s age and comorbidities may be important factors that affect the PDE5-Is response rate. Although we made every effort to the effect of each factors using subgroup analysis, only the regimen of PDE5-I treatment was available for subgroup analysis. Further studies on the effect of the patient’s age and comorbidities on the PDE5-Is response rate are needed.

In terms of the level of evidence, although meta-analysis is at a high level, studies other than RCTs were not included. In addition, although there have been some studies on different subjects of penile rehabilitation, only studies satisfying the criteria for meta-analysis were included in this meta-analysis. In order to overcome these limitations, it is thought that analysis including all studies related to penile rehabilitation is necessary through systemic review in the further study.

Despite these limitations, this meta-analysis corrected some errors that could be found in previous meta-analyses and clearly showed the efficacy of PDE5-Is in patients with ED after NSRP.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis demonstrated the efficacy of PDE5-I treatment in patients with ED after NSRP based on the improvements observed in the IIEF domain score, erectile function recovery, and positive response rate to SEP questions 2 and 3. These efficacies were observed both for daily use and on-demand use of PDE5-Is. In terms of safety, clinically serious adverse effects were not found, although the incidence of TEAEs after PDE5-I treatment was higher than that after placebo treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation and the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (No. NRF-2019M3E5D1A01069353).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-21-881/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-21-881/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tau-21-881/coif). The authors report that this study was funded by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation and the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (No. NRF-2019M3E5D1A01069353); the funders had no role in this study. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Boyle P, Ferlay J. Cancer incidence and mortality in Europe, 2004. Ann Oncol 2005;16:481-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:9-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shao YH, Demissie K, Shih W, et al. Contemporary risk profile of prostate cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:1280-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stephenson RA, Mori M, Hsieh YC, et al. Treatment of erectile dysfunction following therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer: patient reported use and outcomes from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Urol 2005;174:646-50; discussion 650. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zippe CD, Raina R, Thukral M, et al. Management of erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy. Curr Urol Rep 2001;2:495-503. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee R, Penson DF. Treatment outcomes in localized prostate cancer: a patient-oriented approach. Semin Urol Oncol 2002;20:63-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rambhatla A, Kovanecz I, Ferrini M, et al. Rationale for phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor use post-radical prostatectomy: experimental and clinical review. Int J Impot Res 2008;20:30-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rabbani F, Stapleton AM, Kattan MW, et al. Factors predicting recovery of erections after radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2000;164:1929-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geary ES, Dendinger TE, Freiha FS, et al. Nerve sparing radical prostatectomy: a different view. J Urol 1995;154:145-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Catalona WJ, Basler JW. Return of erections and urinary continence following nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol 1993;150:905-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quinlan DM, Epstein JI, Carter BS, et al. Sexual function following radical prostatectomy: influence of preservation of neurovascular bundles. J Urol 1991;145:998-1002. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walsh PC. Radical prostatectomy, preservation of sexual function, cancer control. The controversy. Urol Clin North Am 1987;14:663-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mulhall JP, Graydon RJ. The hemodynamics of erectile dysfunction following nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. Int J Impot Res 1996;8:91-4. [PubMed]

- Tutolo M, Briganti A, Suardi N, et al. Optimizing postoperative sexual function after radical prostatectomy. Ther Adv Urol 2012;4:347-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hatzimouratidis K, Hatzichristou D. Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors: the day after. Eur Urol 2007;51:75-88; discussion 89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zippe CD, Pahlajani G. Penile rehabilitation following radical prostatectomy: role of early intervention and chronic therapy. Urol Clin North Am 2007;34:601-18. viii. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Limoncin E, Gravina GL, Corona G, et al. Erectile function recovery in men treated with phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor administration after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: a systematic review of placebo-controlled randomized trials with trial sequential analysis. Andrology 2017;5:863-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cui Y, Liu X, Shi L, et al. Efficacy and safety of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors in treating erectile dysfunction after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Andrologia 2016;48:20-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Wang X, Liu T, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors for treatment of erectile dysfunction following bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. PLoS One 2014;9:e91327. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration 2011. Available online: http://handbook.cochrane.org

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canat L, Güner B, Gürbüz C, et al. Effects of three-times-per-week versus on-demand tadalafil treatment on erectile function and continence recovery following bilateral nerve sparing radical prostatectomy: results of a prospective, randomized, and single-center study. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2015;31:90-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montorsi F, Brock G, Stolzenburg JU, et al. Effects of tadalafil treatment on erectile function recovery following bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: a randomised placebo-controlled study (REACTT). Eur Urol 2014;65:587-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mulhall JP, Burnett AL, Wang R, et al. A phase 3, placebo controlled study of the safety and efficacy of avanafil for the treatment of erectile dysfunction after nerve sparing radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2013;189:2229-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bannowsky A, van Ahlen H, Loch T. Increasing the dose of vardenafil on a daily basis does not improve erectile function after unilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med 2012;9:1448-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aydogdu O, Gokce MI, Burgu B, et al. Tadalafil rehabilitation therapy preserves penile size after bilateral nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. Int Braz J Urol 2011;37:336-44; discussion 344-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pace G, Del Rosso A, Vicentini C. Penile rehabilitation therapy following radical prostatectomy. Disabil Rehabil 2010;32:1204-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bannowsky A, Schulze H, Jünemann KP. Rehabilitative therapy for erectile function after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Journal of Men’s Health 2010;7:390-5. [Crossref]

- Padma-Nathan H, McCullough AR, Levine LA, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of postoperative nightly sildenafil citrate for the prevention of erectile dysfunction after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Int J Impot Res 2008;20:479-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montorsi F, Brock G, Lee J, et al. Effect of nightly versus on-demand vardenafil on recovery of erectile function in men following bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 2008;54:924-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bannowsky A, Schulze H, van der Horst C, et al. Recovery of erectile function after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: improvement with nightly low-dose sildenafil. BJU Int 2008;101:1279-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nehra A, Grantmyre J, Nadel A, et al. Vardenafil improved patient satisfaction with erectile hardness, orgasmic function and sexual experience in men with erectile dysfunction following nerve sparing radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2005;173:2067-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cavallini G, Modenini F, Vitali G, et al. Acetyl-L-carnitine plus propionyl-L-carnitine improve efficacy of sildenafil in treatment of erectile dysfunction after bilateral nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urology 2005;66:1080-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montorsi F, Nathan HP, McCullough A, et al. Tadalafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction following bilateral nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Urol 2004;172:1036-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brock G, Nehra A, Lipshultz LI, et al. Safety and efficacy of vardenafil for the treatment of men with erectile dysfunction after radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol 2003;170:1278-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang R. Penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy: where do we stand and where are we going? J Sex Med 2007;4:1085-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet 2017;390:415-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldstein I, Lue TF, Padma-Nathan H, et al. Oral sildenafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Sildenafil Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1397-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takimoto E, Champion HC, Li M, et al. Chronic inhibition of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase 5A prevents and reverses cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med 2005;11:214-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Marhin T, et al. Sildenafil inhibits beta-adrenergic-stimulated cardiac contractility in humans. Circulation 2005;112:2642-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jackson G, Kloner RA, Costigan TM, et al. Update on clinical trials of tadalafil demonstrates no increased risk of cardiovascular adverse events. J Sex Med 2004;1:161-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hatzichristou D, Montorsi F, Buvat J, et al. The efficacy and safety of flexible-dose vardenafil (levitra) in a broad population of European men. Eur Urol 2004;45:634-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Padma-nathan H, Eardley I, Kloner RA, et al. A 4-year update on the safety of sildenafil citrate (Viagra). Urology 2002;60:67-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nandipati K, Raina R, Agarwal A, et al. Early combination therapy: intracavernosal injections and sildenafil following radical prostatectomy increases sexual activity and the return of natural erections. Int J Impot Res 2006;18:446-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deng H, Liu D, Mao X, et al. Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibitors and Vacuum Erection Device for Penile Rehabilitation After Laparoscopic Nerve-Preserving Radical Proctectomy for Rectal Cancer: A Prospective Controlled Trial. Am J Mens Health 2017;11:641-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]